Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (32 page)

Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

Personally, although the overall argument is attractive, I find the rest of Guthrie’s list over-inclusive and I am not at all convinced by the argument about small nose size. In Europe, both modern Europeans and Neanderthals seem to have selected for large noses as air conditioners to warm and moisten air about to enter sensitive lungs.

This seems a convincing enough reason for big noses and, if correct, would clearly have happened independently twice. How can small noses then also be good for the cold? Eskimos and, to a lesser extent, the Chuckchis of north-east Siberia have what has been referred to as a ‘pinched’ nose’ – a projecting nose set in a very flat upper face.

19

This further adaptation in extreme northern Mongoloids suggests that the small nose was not a particularly good air conditioner in the first place and required modification in the Arctic.

Perhaps the strongest pieces of internal evidence (by which I mean consistency of degree in actual observations based on predictions of the theory) for the adaptations occurring to the north, where Guthrie said they did, are the relatively paler skin found in Northern Mongoloids, and the most extreme physical changes, such as facial flattening, having occurred around Lake Baikal in both ancient and in modern populations.

20

Guthrie also speculates on how long these adaptive changes took and when they started. Reasonably, he views the last glacial maximum 20,000 years ago as the climax of cold stress that produced most change, but he suggests that the whole process started as long ago as 40,000 years. What might support this longer timescale is that, as already mentioned, Mongoloid changes such as facial flattening are known from the west of Lake Baikal from before the last glaciation (see

Figure 5.3

).

Although I am tempted by Guthrie’s story as far as the evolutionary pressures are concerned, I have a problem with the scarcity of hard physical evidence in the fossil record. There is also the major question of how the Southern Mongoloids of tropical Southeast Asia gained their characteristic features in the first place if they are supposed to be descended from the stay-at-homes. If the whole package of features common to both Northern and Southern Mongoloids is primarily due to cold adaptation, then, according to the south–north theory, it should not be present in Southern

Mongoloids. As an anecdotal aside, I can record that my dear wife, whose ancestors are all from the south coast of China and who in the classification I am using here is therefore Southern Mongoloid, is far less tolerant of cold than I am, consistent with an ultimate southern origin!

If the south–north and cold-adaptation theories are both correct, we have to concede that the initial physical changes may have resulted from an evolutionary mechanism other than adaptation to cold, and that some of those changes were later serendipitously amplified by cold selection.

Neoteny in humans

I am drawn to Guthrie’s explanation of evolutionary pressures in the north, but also favour an initial south–north movement on the basis of dental and genetic evidence. There is another evolutionary phenomenon that may bridge the two. An interesting hypothesis put forward by palaeontologist Stephen Jay Gould many years ago was that the package of the Mongoloid anatomical changes could be explained by the phenomenon of neoteny, whereby an infantile or childlike body form is preserved in adult life. Neoteny in hominids is still one of the simplest explanations of how we developed a disproportionately large brain so rapidly over the past few million years. The relatively large brain and the forward rotation of the skull on the spinal column, and body hair loss, both characteristic of humans, are found in foetal chimps. Gould suggested a mild intensification of neoteny in Mongoloids, in whom it has been given the name ‘paedomorphy’.

21

Such a mechanism is likely to involve only a few controller genes and could therefore happen over a relatively short evolutionary period. It would also explain how the counter-intuitive retroussé nose and relative loss of facial hair got into the package.

There are several evolutionary mechanisms by which paedomorphic individuals could produce relatively more offspring over

time, which could operate through drift or selection, and which are not mutually exclusive. One could be through an association with thrifty genes, useful for the cold steppe (decrease unnecessary muscle bulk, less tooth mass, thinner bones, and smaller physical size); this follows the selective/adaptive model of Mongoloid evolution, which could have made use of pre-existing traits that just happened to arise among Sundadont populations migrating up the coast from the south. Equally, paedomorphic women may have been more highly prized for looking cuter: this is more of a sexual selection and drift hypothesis and, again, while further exaggerated drift or selection may have occurred in the north, the pre-existing traits could have ultimately come from the south.

I would argue that both mechanisms came into play in Mongoloid development. Southern Mongoloid features could have developed initially as a result of sexual selection and/or drift. Then, as some of those peoples moved north into Central Asia, there would have been further ‘development on the theme’ in response to the evolutionary pressures Dale Guthrie so vividly describes. In a sense, therefore, there were two homeland platforms for the development of Mongoloid features. This armchair theory has no immediate scientific support since geneticists are, as yet, only on the threshold of understanding the genes that control growth and body moulding, let alone detecting meaningful differences within our own species. On the other hand, genetic tracking may be able to help with the direction of migration.

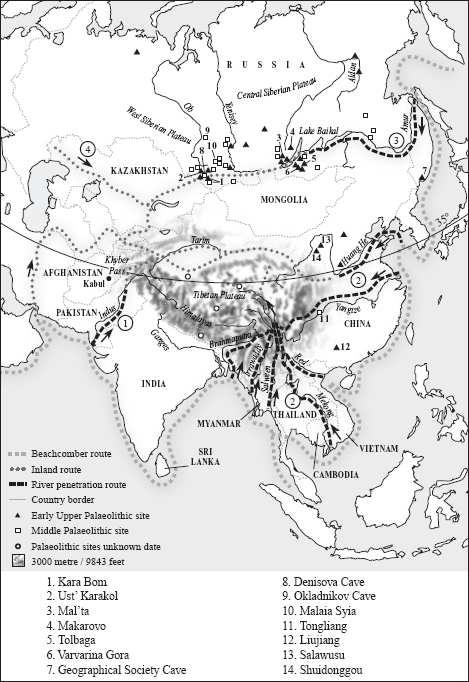

Four routes into Central Asia

As with all previous explorations, by both modern and archaic humans, geography and climate decided the newly arrived occupants of Asia where to go next. The rules would have been simple: stay near water, and near reliable rainfall; when moving, avoid deserts and high mountains and follow the game and the rivers. We have seen circumstantial evidence that the beachcombing route

round the coast of the Indian Ocean to Australia was the easiest and earliest option. Why should this have been? It was not that easy: for a start, every few hundred kilometres our explorers would have had to ford a great river at its mouth. Yet this is just what they must have done to get to Australia, so it is possible they did the same along the East Asian coast. At each river there was the option for some people to turn left and head inland, harvesting river produce and game as they went.

As one of the earliest European explorers, Marco Polo, found out, mountains and deserts present formidable barriers to those trying to gain access to Central Asia; apart from a few trails, the only routes of entry are along the river valleys. We have seen that our first successful exodus from Africa took the ancestors of all non-Africans south along the Indian Ocean coast perhaps as long ago as 75,000 years. They may also have beachcombed as far as eastern China and Japan rather early on. They would thus have skirted the whole of the Central Asian region. They could have tried to head upriver and inland at any point on their journey.

North of India, with the Himalayas in the way, it was not as straightforward as that. The raised folds of mountains caused by India’s ancient tectonic collision with Asia extend either side of Nepal and Tibet well beyond the highest Himalayas. A vast band of mountains, all over 3,000 metres (10,000 feet), blocks Central Asia to access from the Indian Ocean coast for a distance of 6,500 km (4,000 miles) from Afghanistan in the west to Chengdu, in China, to the east. This band is rucked up like a carpet in the east, thus extending the mountain barrier south as a series of north–south ridges over a distance of about 2,500 km (1,500 miles) from the beginning of the Silk Road in northern China south to Thailand.

The Silk Road, first made famous in the West by Marco Polo, is a long trading route, parallel to and to the north of the Himalayas, connecting West with East. It passes right through Central Asia, directly along the southern edge of Guthrie’s Mammoth Steppe

heartland. The Silk Road was then, as it is now, one of the few links between China and the West, if the long coastal route round south via Singapore was to be avoided.

East along the Silk Road from the west end of the Himalayas

Today the Silk Road skirts both the southern and northern edges of the Taklamakan Desert of Singkiang. During the Palaeolithic, what is now desert was mostly lush grassland, and farther north a series of waterways, including the Tarim and Dzungaria rivers, provided easy west–east access for hunters from the western Central Asian regions of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kirghistan, and Kazakhstan into Singkiang and Mongolia. These waterways may have been used by earlier humans to get to Central Asia.

22

To look at Stone Age practicalities, let us take the first access route to Central Asia up the Indus, 8,000 km (5,000 miles) to the west of China at the western end of the Silk Road. Assuming for the moment that we are talking about an offshoot of the first Indian beachcombers, their first task after moving up the Indus would have been to negotiate the mountain barriers to the north of India and Pakistan. These extend as far west as Afghanistan. Bypassing the mountains and moving through Afghanistan too far to the west would have been difficult if not impossible, since it was near-desert. Marco Polo crossed these deserts, leaving from Hormuz at the mouth of the Gulf and passing through Afghanistan to Kashmir, crossing a high pass directly into China and the city of Kashgar, to arrive well along the Silk Road and directly in the heartland of the former Mammoth Steppe (

Figure 5.5

).

Marco Polo could have followed a much easier route to Kashmir, however. From the coast of Pakistan a little further to the east, the great Indus snakes northward to a point where there is a water connection through to Kashmir. Another lower-altitude route into Central Asia, also via the headwaters of the Indus, would have been to cross the Khyber Pass to Kabul, and thence to Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, and then east towards Singkiang.

Figure 5.5

Four Palaeolithic routes into Central Asia. Access to Central Asia has always been limited by the Himalayas, their flanking ranges and various deserts. The possible routes of entry, mainly via the great Asian rivers, are shown here and apply to the following maps in this chapter and the next. Earliest human settlements also shown.

West along the Silk Road from China

Equally, during all of human history, the Silk Road has been the only route west from China into Central Asia. So, an alternative route into the Mammoth Steppe would have been from the East Asian Pacific coast. The vanguard of the earliest beachcombers could have gone all the way to China and then moved west from northern China along the Silk Road into Mongolia, Sinkiang, and southern Siberia.

North into Tibet from Burma

The third access route to the Mammoth Steppe, not much used by traders today, is just to the east of the Himalayas. The eastern edge of the Himalayas consists of multiple folds where the edge of the Indian plate rucked up the Asian continent on collision. We can see from the map (see

Figure 5.5

) that these rucks are the conduits for most of the great rivers of South and Southeast Asia. From west to east, these are the Brahmaputra, which flows into Bangladesh, the Salween, which flows into Burma, the Mekong, which flows into Vietnam, and the Yangtzi, which flows into southern China. As they flow out of south-east Tibet these four major rivers run parallel for about 150 km (around 100 miles), separated from one another by only a few kilometres. The last of the four, the Yangtzi, originates in north-east Tibet near the northern edge of the plateau and at the beginning of the Mammoth Steppe. I mention these multiple river routes not because many legitimate traders use them today, but because they allow direct access to Tibet, Mongolia, and Central Asia from any of four widely separated river mouths in Southeast and East Asia discharging on to the Indo-Pacific coast. Also, as we shall see, Tibet shares much genetically with Indo-China and Southeast Asia.

East from Russia

Finally, there is another, more northerly route of migration from the West into East Asia to be considered: via Asian Russia, known as the Russian Altai. The easiest direct land access from the Russian Altai to Central Asia during the milder parts of the

Late Stone Age 30,000–50,000 years ago would have been to cross the steppe directly. Travelling east through southern Siberia via a series of lakes and waterways, our ancient explorers could have reached the Lake Baikal region by a route passing north of Singkiang and Mongolia. At that time the steppe covered the whole region in greensward and open woodland. Clearly, for modern humans to have taken this route they must have got to the Russian Altai in the first place. As we shall see, they had reached both the Russian Altai and Lake Baikal in southern Siberia by 40,000 years ago.