Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (27 page)

Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

There are other signs that the ancient African genetic diversity has been preserved in Pakistan. While the population of Pakistan in general shares some ancient mtDNA links with India, Europe and the Middle East, they also possess unique markers that are found nowhere else outside Africa. There are indeed populations that hark back to that ancient connection. One aboriginal so-called Negrito group, the Makrani, is found at the mouth of the Indus and along the Baluchistan sea coast of Pakistan. It is speculated that they took the coastal route out of Africa. They have an African Y-chromosome marker previously only found in Africa which is characteristic of sub-Saharan Africa. The same marker is found at slightly lower frequencies throughout other populations of southern Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, and at higher rates in Iran. Another unique Y-chromosome marker appears outside Africa only in this region (see Note 31). One other ancient Y-chromosome marker points specifically to Pakistan as an early source and parting of the ways. This is an early branch off the Out-of-Africa Adam that is present at high frequency in Pakistan and at lower frequencies only in India (especially in tribal groups) and further north in the Middle East, Kashmir, Central Asia, and Siberia. The fact that this marker is not found farther east in Asia suggests that the only way it could have arrived in Central Asia was by a direct early northern spread up the Indus to Kashmir and farther north.

31

The origins of Europeans: where was Nasreen born?

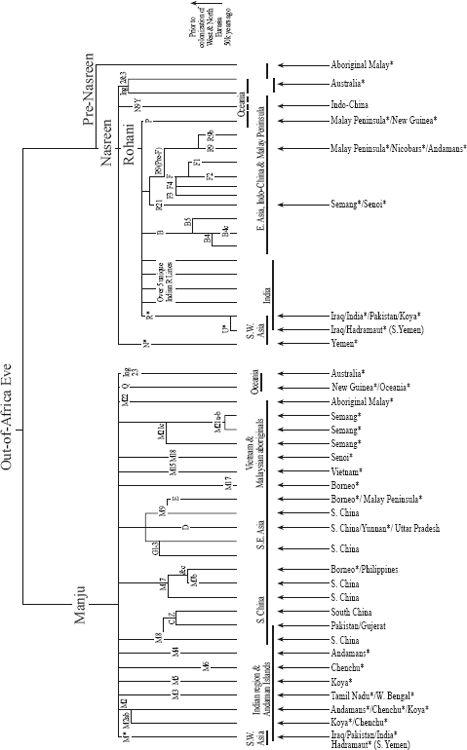

The prime position of South Asia in retaining African genetic diversity brings us to discuss the South Asian site of the parting of the ways. And we can now focus on the power of our maternal and paternal gene trees to leave trails of their ancient movements. Although the finding of roots and early branches of the Nasreen and Manju lines along the South Arabian and Baluchistan coastlines is strong evidence for the idea that a single southern out-of-Africa exodus continued first to South Asia, it does not necessarily identify the exact site of origin of Nasreen or her six Western daughters, including Rohani, or of Rohani’s own West Eurasian daughters (U, HV, and JT) (

Figure 4.2

). Although Rohani clearly derives from somewhere in South Asia (see below), the birthplace of her West Eurasian daughters is less clear but of great interest. However, when we look at the mitochondrial genetic make-up of the whole of the Near East (including the Levant, Anatolia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, northern Kurdistan, as well as more southerly regions such as the Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Iran) as revealed by the European founder analysis of Martin Richards and colleagues we find the greatest genetic diversity of Rohani’s western daughters in the Gulf state of Iraq (see

Chapter 3

). Notable in Iraq are the high rates of unclassified root genetic types and the absence of other non-Rohani western daughter groups of Nasreen, such as W, I, or X. So it may be that Rohani’s western daughters were born farther south, in Mesopotamia or near the Gulf, either before or during the first northward migration up the Fertile Crescent.

32

Such questions can be sorted out only by a formal founder analysis, such as that used by Martin Richards and colleagues to trace the European founders, but this time comparing South Asian regions with the Levant. My own view is that for Rohani’s Indian granddaughter U2i to be of a similar age, around 50,000 years, to her sister U5 in Europe, it is simplest for both Rohani and her daughters (Europa, HV, and JT) to have been born down south in the Gulf region, halfway between India and Europe. Certainly, as we saw in

Chapter 3

, a strong argument can be made for several early non-African Y-chromosome groups having their roots in southern Asia rather than up in the Levant.

33

Figure 4.2

The beachcomber mtDNA tree. Shows mtDNA branches found along the Indo-Pacific coast, Oceania and the Antipodes. In each, genetic continuity of spread can be seen from South Asia to Japan and to the south-west Pacific. Horizontal lines are for regional representation, vertical arrows for specific local representation; names with a star (‘*’) indicate putative relict populations from the trek.

South Asia: fount of all Asian lines?

While little has been published on genetic markers for the southern Arabian peninsula, there is a magnificent body of information on the Indian subcontinent. For mitochondrial DNA we have an Estonian genetics team, with Asian collaborators, to thank for much of this, and several European and American groups are now collaboratively working on the Y chromosome. While this may bias our attention to India and Pakistan, the focus is deserved. Pakistan is the source of the Indus, the main route for direct access from South Asia to Central Asia west of the Himalayas. India, Bangladesh, and Burma also harbour the great southern Asian rivers, the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Salween, draining the south and east of the Himalayas.

With the diversity of its inhabitants’ physical appearance and their cultures, peninsular India is a rich transitional ethnic and geographical zone between West and East Eurasia. To the north and west we see only a very gradual change in people’s appearance, including pigmentation (see

Chapter 5

), as we move from Pakistan, through Afghanistan and Iran, and west into Europe. The similarities between many South Asians and Europeans are striking.

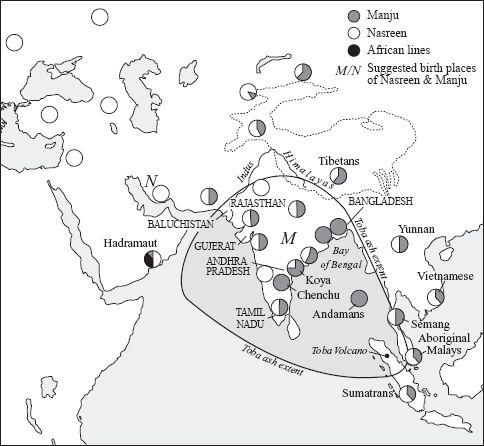

This gradual east–west transition across northern India and Pakistan is paralleled in the relative frequencies of the two genetic daughter super-clans, Nasreen and Manju of the Out-of-Africa Eve founder line (L3). (

Figure 4.3.

) When we look at the Hadramaut in the Yemen, these frequencies are in the ratio 5:1 Nasreen to Manju, consistent with the view that Nasreen originated farther west than Manju, in the Gulf region. Between the Red Sea and the mouth of the Indus in Pakistan, West Eurasian genetic descendants of Nasreen continue to outnumber those of our Asian super-clan Manju. As we move east across the mouth of the Indus in Baluchistan and on towards India, the picture begins to change. The ratio of Nasreen to Manju lines decreases to 1:1 in the far-western states of Rajasthan and Gujerat. By the time we get to Bengal and Bangladesh, the ratio has reversed and Manju dominates. We thus find that the dominant clan in India is Manju, with an increasing frequency as we move from west to east.

34

To the north and east of India, however, the changes are even more abrupt. In Nepal, Burma, and eastern India we come across the first Mongoloid East Asian faces. These populations generally speak East Asian languages, contrasting strongly with their neighbours who mostly speak Indo-Aryan or Dravidian languages. By the time we get to the east of Burma and to Tibet on the northern side of the Himalayas, the transition to East Asian appearance and ethnolinguistic traditions is complete, as is the rapid and complete change of the mitochondrial sub-clans of Manju and Nasreen. In Tibet, for instance, the ratio of Manju to Nasreen clans has evened back to 3:1, and there is no convincing overlap of their sub-clans with India (see

Figure 4.2

). Instead, Tibet shows 70 per cent of typical East and Southeast Asian Manju and Nasreen sub-clans, with the remainder consisting of as-yet unclassified Manju types of local origin. The north-eastern part of the Indian subcontinent therefore shows the clearest and deepest east–west boundary.

35

This boundary possibly

reflects the deep genetic furrow scored through India by the ash-cloud of the Toba volcano 74,000 years ago.

Figure 4.3

Distribution of Nasreen and Manju in South Eurasia. In West Eurasia there is only Nasreen; in most of East Eurasia there are even mixtures of Nasreen and Manju, but on the east coast of India there is nearly all Manju. The latter is consistent with near local extinction following the Toba explosion with recovery only of Manju on the east coast.

To the south of the Indian peninsula, the main physical type generally changes towards darker-skinned, curly haired, round-eyed so-called Dravidian peoples (see

Chapter 5

). Comparisons of skull shape link the large Tamil population of South India with the Senoi, a Malay Peninsula aboriginal group intermediate between the Semang and Aboriginal Malays (see above).

36

Manju born in India, Nasreen possibly a little farther west in the Gulf

Manju, who is nearly completely absent from West Eurasia, gives us many reasons to suspect that her birthplace is in India. Manju achieves her greatest diversity and antiquity in India. Nowhere else does she show such variety and such a high proportion of root and unique primary branch types. The eldest of her many daughters in India, M2, even dates to 73,000 years ago. Although the date for the M2 expansion is not precise, it might reflect a local recovery of the population after the extinction that followed the eruption of Toba 74,000 years ago. M2 is strongly represented in the Chenchu hunter-gatherer Australoid tribal populations of Andhra Pradesh, who have their own unique local M2 variants as well as having common ancestors with M2 types found in the rest of India. Overall, these are strong reasons for placing Manju’s birth in India rather than further west or even in Africa.

37

The spectrum of Nasreen types in India is also different from further west. Although her granddaughter Europa types are present in 13 per cent of all Indians surveyed, these are nearly all accounted for by two Europa sub-branches, U7 and U2i (the Indian version of the U2 clan), along with a scattering of other Europa clans also found in the West, with virtually no root Nasreen types. This suggests that although U7 and U2i are both very ancient South Asian clans, they entered from further west at the time of the first colonization of Europe from South Asia 50,000 years ago – well

after

the initial out-of-Africa trek. There is also no evidence which would place the origin of Nasreen in India proper, although a scattering of her first-generation daughters, who have West Eurasian counterparts, is found there.

38

The real surprise among Nasreen’s clan representatives in India is her daughter Rohani. If we recall, Rohani is Nasreen’s most prolific daughter, being mother to most Westerners including Europa, not

to mention two Far Eastern daughters with very large families (see Fig 4.2). In India, Rohani makes even that fecundity look like family planning. Estonian geneticist Toomas Kivisild has identified numerous other Rohani daughter branches, apparently all originating in India and none of them shared any other region. So rich are these new branches that he has been able to date their expansion to around 73,000 years ago.

39

Nowhere else, west or east, do we find such deeply branched diversity in the Rohani genetic line. On this basis alone there is a strong case for identifying South Asia as Rohani’s birthplace. It would seem more logical for Rohani and her European daughters to have been born in the Gulf than in India; but there is no genetic evidence as yet for that. Given the short distances and great time depth, however, either scenario is possible. One thing seems extremely unlikely, and that is that Rohani was born in the Levant or Europe. No Rohani roots are found anywhere in those regions to support that possibility, thus again slamming the door shut on any early northern migration out of sub-Saharan Africa.

What is perhaps most interesting about the unique Indian flowerings of the Manju and Rohani clans is a hint that they represent a local recovery from the Toba disaster which occurred 74,000 years ago, after the out-of-Africa trail began. A devastated India could have been recolonized from the west by Rohani types and from the east more by Manju types. Possible support for this picture comes from the recent study by Kivisild and colleagues of two tribal populations in the south-eastern state of Andhra Pradesh.

40

One of these populations, the Australoid Chenchu hunter-gatherers, are almost entirely of the Manju clan and hold most of the major Manju branches characteristic of and unique to India. The other group, the non-Australoid Koyas, have a similarly rich assortment of Indian type Manju branches (60 per cent of all lines), but have 31 per cent uniquely Indian Rohani types. The Chenchu and Koya tribal groups thus hold an ancient library of Indian Manju and Rohani genetic lines

which are ancestral to, and include, much of the maternal genetic diversity that is present in the rest of the Indian subcontinent. Neither of these two groups holds any West Eurasian Nasreen types. The presence of Rohani types in the Koyas but not in the Australoid Chenchus might fit with some component of a recolonization from the Western side of the Indian subcontinent. As evidence of their ancient and independent development, and in spite of their clearly Indian genetic roots and locality, there were

no

shared maternal genetic types (i.e. no exact matches) between the two tribal groups thus indicating deep antiquity.