Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (31 page)

Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

Figure 5.3

Map of Mongoloid types and dental differentiation in East Asia. Sundadont and Sinodont dental types occupy roughly the same areas as Southern Mongoloid and Northern Mongoloid, respectively, except in South China, where the Yangtzi River divides Northern from Southern Mongoloid. The islands of Sakhalin and Japan are excluded since the aboriginal group, the Ainu, and their Jomon ancestors show partial Sundadonty.

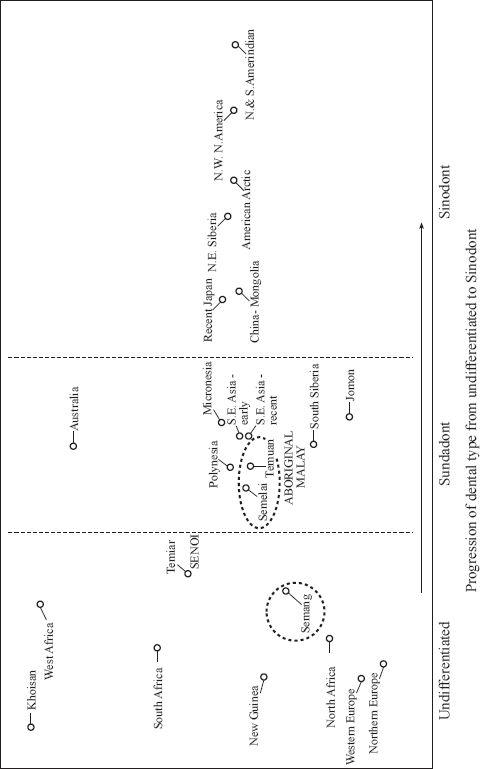

Figure 5.4

Two-dimensional plot of the spread of dental morphology. The spectrum runs from undifferentiated (Africa, Europe, relict aboriginal Semang and Senoi groups and New Guinea) through Sundadonty (Aboriginal Malay, Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders) to Sinodonty (Northern Mongoloid and Native American groups). Narrowing of plot indicates reduction of diversity away from Africa. Jomon and South Siberians are notable outliers.

Australian aboriginals occupy an interesting position in this spectrum (see

Figure 5.4

) in that they show some features of Sundadonty, unlike their neighbours the New Guineans. This tends to confirm the possibility of some admixture.

15

Second of the two important derived dental groupings of Eurasia after Sundadonty is Sinodonty (literally, ‘Chinese teeth’). Sinodont people are characterized by an exaggeration of certain tooth shapes already present in Sundadonts and also, generally, a reduction in tooth size. Sinodonty is characteristic of mainland Asian Northern Mongoloid peoples, increasing in degree towards the north and extending to include the Americas (see

Figure 5.3

). Sinodonty is uncharacteristic of Southeast Asia, even today.

As an oversimplification, Sundadonty represents the earliest dental change from the out-of-Africa beachcombers, and combinations of its features are found both in Southern Mongoloids of Southeast Asia, Polynesia, and Micronesia, and, to a lesser extent, in some non-Mongoloids such as the Jomon of Japan and the isolated Andaman Islanders. Sinodonty represents a further divergent trend in the same morphological direction as Sundadonty and is found in

Northern Mongoloids, including most Chinese, and in an even more exaggerated form in Northeast Siberians and Native Americans.

16

The enigma of Mongoloid origins

What is clear, whether one looks at skull shape, teeth, or genetic markers, is that of all the groups outside Africa, Mongoloid populations have changed or drifted the most since the exodus. This differentiation from the ancestral type and loss of group diversity increases in today’s populations as we go northwards in East Asia and then east into Arctic America. What is not at all clear is how, when, and where the features that distinguish Mongoloids from all other Eurasians developed. These are not idle academic questions. Mongoloids are, after all, the world’s most numerically successful and widespread physical type. They arrived in America before the last glaciation 20,000 years ago (see

Chapter 7

), yet they do not definitely appear in lowland China until well after that icy bookmark in human history. We can summarize the rather complex story so far as follows:

1 The very first Asians (who were also the ancestors of the Europeans) looked rather like the Africans of that time and probably had similar teeth.

2 Those first undifferentiated robust South Asians, starting from 85,000 years ago, spread out all along the South Asian coastline from the southern Arabian coast, through India, to Southeast Asia, also reaching New Guinea at the end of the arc in the south-west Pacific. The present-day relict descendants along that route have retained ancestral tooth features.

3 From Indo-China, these undifferentiated types also spread north to China, moving round the western rim of the Pacific Ocean between 35,000 and 70,000 years ago.

4 At some time

before

the last glaciation, a new complex of tooth shape called Sundadonty developed among ‘pre-Mongoloid’

people living in Southeast Asia. These new dental types subsequently spread, in modified form, north-east along the Pacific coast to Japan (the prehistoric Jomon and modern Ainu) and south-east to Polynesia (see

Figure 5.3

).

5 A second dental complex, Sinodonty, is probably much more recent and is derived from Sundadonty. The evolution from Sundadonty to Sinodonty does not seem to have happened in Southeast Asia or along the west Pacific coastline among the Jomon or Ainu of Japan; but the degree of Sinodonty increases as we move north through the modern Mongoloid populations of mainland East Asia, and it reaches its extreme in the Americas. So, it appears that Sinodonty originated with Sundadonts from the south. Due to lack of fossils, Sinodonty has not been detected from any earlier than 10,000 years ago in South China or in Japan.

6 The Mongoloid skull shape is characterized by delicate gracile bones, marked facial flattening, and length shortening. Nasal flattening is found in one skull from just before the LGM, in the region around Lake Baikal. Facial flattening is still most marked in that region.

7 Like Sinodonty, Mongoloid features have not been detected in Chinese fossils from before the LGM. More recently they have spread widely in North and East Asia and are characteristic of Sinodonts – in other words Northern Mongoloids – as well as of most Native Americans.

The progressive change in skull features thus appears to have been paralleled by the change from Sundadonty to Sinodonty. If the ancestors of Sinodonts were Sundadonts from the south, then at least some of the other physical features that characterize Northern Mongoloids may also have originated in the south. If the first characteristically Mongoloid ancestors of Northern Mongoloids came from the south, they would share ancestors with peoples, such as the Aboriginal Malays, who still live there. As we shall see later, there is

good supporting evidence that at least some of the major gene lines in East and Northeast Asia derive ultimately from Indo-China, with ancestral types still found among aboriginal Southern Mongoloids of the region.

It is worth pausing to review the various implications and consistency of this south–north as opposed to north–south model of movement and change in teeth and bones. Of the two East Asian dental types today associated with Mongoloid peoples, Sundadonty probably originated rather early in Southeast Asia, representing the earliest dental change, still being found in some non-Mongoloid relict populations. Sinodonty, on the other hand, is commonest over most of East Asia and the Americas but is, even now, not found in indigenous Southeast Asians. This latter observation favours the south–north view.

What about admixture from the north? If this is how Southern Mongoloids arose, we would expect, merely by association and carry-over, to find Sinodonty massively intruding into Southeast Asia – which we do not. Simple observation of degree of change also backs up the theory that dental types evolved first into Sundadonty in the south, and then drifted towards Sinodonty as the Mongoloid peoples moved into Central Asia.

As with the progression and exaggeration of Sundadont features resulting in the Sinodont type, some Mongoloid features, such as facial flatness, are more exaggerated in Northern Mongoloids than in Southern Mongoloids. So, whatever evolutionary force was driving those specific changes must have continued to apply somewhere farther north, perhaps in the interior. Fossil evidence (or rather, lack of it) suggests that the region of ‘further development’ of Mongoloid features was not China, Japan, Southeast Asia, or India – which leaves somewhere in Central Asia north of the Himalayas, such as Mongolia or the Lake Baikal region in southern Siberia. Furthermore, there is one particular southern Siberian group

which features a cluster of Sundadonts among its people, unlike the rest of that region, suggesting a local retention of ancestral type (see

Figure 5.4

).

Why did Mongoloid peoples come to look different?

There have been a number of theories of how and where Mongoloid skeletal features developed. The first thing to say is that all these theories are highly speculative and even contentious. The ‘where’ theories are speculative mainly, as I have pointed out, because of the overall lack of early Mongoloid fossil evidence. The ‘how’ theories are speculative because at present there is no way of linking particular skeletal changes to specific controller genes. However, this should not prevent us from at least looking at the theories.

Unfortunately, as with many scientific debates, controversy usually ends in a split between two opposite views, when the truth probably lies somewhere in between. For origin theories we are left having to choose between southern homeland and a northern one, and for the ‘how’ theories we have adaptive physical evolution in response to cold versus simple isolation and genetic drift. (There is some linkage between the two proposed mechanisms of change, since the adaptive theories specify a cold northern zone of adaptation.)

The north–south geographical division has been etched even deeper by physical (and genetic) evidence, old and new, that the Northern and Southern Mongoloid populations can indeed be separated. Studies of child growth curves in China, for instance, have shown that Hong Kong children in the south, although well nourished, are smaller than those from Beijing in the north. The fact that the better-nourished Hong Kong children are still a different size from those in Beijing, even after generations of booming development, suggests that there is a systematic genetic difference between north and south.

17

Do Mongoloid features result from drift or selection?

The main alternative ‘how’ solutions to the origins of Mongoloids are fairly easy to state. The simplest answer (discussed in the last chapter) is that a small founder group isolated from other groups will drift randomly toward one genetic or physical type. These combined founder and drift effects can be exaggerated by sexual selection. To take an absurdly oversimplified example, imagine that the founder Mongoloid group, in this instance coming from the south, has by chance a higher proportion of smaller rather than larger noses. As a result of group identity, or maybe of preference in choosing a sexual partner, retroussé noses (small and turned up at the tip) may then become the preferred physical type in the group. That will reinforce drift towards small noses, and the descendants of the group will all end up having very small noses. Other features genetically associated with small noses, such as flat faces, also get drawn into the drift.

The other theory, older and perhaps most contentious, is that Mongoloid founders somehow adapted to cope with a changed and hostile environment, in this case the much colder and windier conditions of the Asian Steppe north of the Himalayas. This idea has a long pedigree, but is perhaps best articulated by American biologist Dale Guthrie. Guthrie has persuasively described what he calls the Mammoth Steppe of Palaeolithic Asia. The Mammoth Steppe was in reality a vast, high grassland whose heartland was in the region north of the 35th parallel, the Himalayas and the Tibetan plateau. Also known to biologists as the Palaearctic biome, the whole complex cold habitat disappeared from 10,000 years ago, as a paradoxical result of global warming, taking with it a whole range of large and small fauna and flora for ever.

18

According to Guthrie, the southern heart of the steppe was occupied by early modern humans spread across Singkiang, Mongolia, and the Lake Baikal region of Siberia. These are areas that

now contain large expanses of desert. At its greatest extent the Mammoth Steppe stretched from the Atlantic coast of Europe in the west to Hokkaido in the east. It was the greatest grassland the world had ever seen, and it supported almost limitless herds of large herbivores. Some of these herbivores still survive in a severely reduced range and mostly in small numbers – they include wild horse, reindeer, musk-ox, and saiga antelope – but the large ones – woolly mammoth, steppe bison, and woolly rhinoceros – became extinct.

Clearly, the Mammoth Steppe would have been paradise for hunters who could cope with the intense cold, dry winds. Guthrie suggested that the Palaeolithic peoples who preyed on the herds of the steppe tended to inhabit the warmer southern fringes around the 40th parallel, where there were more islands of forest shelter (see

Figure 5.3

). It is certain that people living in such cold conditions would have needed clothing. Guthrie and others have suggested a number of physical adaptations which would have helped Mongoloids to cope with this harsh environment. They include the double upper eyelid, or fatty epicanthic fold, to reduce heat loss from the eye; more insulating subcutaneous fat padding around the eyes on the cheeks, jaw, and chin; a smaller nose profile to reduce the risk of frostbite; a rounder head with fewer angles which loses less heat; a shorter, stockier body with relatively shorter limbs; a more even distribution of fat which, with the changes in limb proportion, gives an overall reduction of 10 per cent in surface-to-volume ratio; a pale skin like that of Europeans, allowing adequate vitamin D production against rickets; and an enhanced response of blood vessels in the limbs to avoid frostbite.