Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (29 page)

Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

Nowhere else outside Africa do we find such a diversity of deep Y roots and branches except, to a much lesser extent, in Central and North Asia. This picture of Central Asia as another transition zone between East and West is borne out in the rich mixture of European

and Asian maternal mtDNA lines also found in that region,

54

suggesting that one of the primary splits after the arrival in India was to travel north up the Indus to Central Asia. This early inland route is one of the main topics of the next chapter.

In summary, the South Asian region, the first homeland of that single, successful southern exodus, shows the presence of the genetic roots of that expansion not only in the so-called aboriginal peoples around the Indian Ocean, but among the bulk of the modern populations. Among these roots we can detect genetic base camps for the most westerly of the subsequent pioneer treks inland to the vast Eurasian continent. These treks set off, after a pause, for Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. It seems that the vanguard of the beachcombing trail retained a surprising proportion of the original genetic diversity left in the out-of-Africa group and moved rather faster round the shores of the Indian Ocean. So fast, in fact, that they travelled right round to Indonesia and on into Near Oceania, arriving in Australia long before their first cousins made it to Europe.

The exact chronological relationship of the exodus and the subsequent arrival in Southeast Asia to the massive Toba volcanic explosion of 74,000 years ago is critical. First, Toba is one of the most accurately and precisely dated events of the Palaeolithic, and its ashfall acts as a time datum for the whole of southern Asia. Second, the effects of Toba’s direct ashfall followed by the inevitable ‘nuclear winter’ would have been disastrous for any life in its path, and pretty bad farther afield. The presence of tools thought to be made by modern humans found with Toba ash in the Malay Peninsula suggests that the beachcombing vanguard had arrived in the Far East before the eruption. Triangulation of this anchor date with other pieces of evidence supports this scenario. Other clues include new dates for the Liujiang skull, luminescence dates from Australia, the date of the lowest sea level enabling passage to Australia at 65,000 years ago, genetic dates of the expansion of the L3 group at 83,000 years

ago, and the onset of significant salinization of the Red Sea dated to 85,000 years ago. The best evidence for early modern humans in Asia should come from real fossils and their dated context. Such work is in process at the site of Liang Bua in Flores.

Now, if Toba really did blow its top after India was first colonized, we would expect a mass extinction event on the Indian Peninsula which affected the eastern side more than the west. This is certainly one interpretation of the paradox of the Indian genetic picture, in which the genetic trail of the beachcombers can be detected, but the bulk of Indian subgroups of Manju and Rohani are unique to the subcontinent, especially among the tribes of the south-east. This is what we would expect for a recovery from a great disaster. The oldest of these local lines have been dated to around 73,000 years ago.

In the next chapter we shall see what those pioneers did on the North and East Asian mainland after they arrived, and how they got to those places.

T

HE EARLY

A

SIAN DIVISIONS

W

E ALL HAVE A TENDENCY

to see differences. ‘Mummy, why does that person look like that?’ is a question we hear on children’s lips from an early age. So why is it that people from different parts of the world all look so different? Why are children and adults so interested in these things? To many people the issue of physical difference is loaded with that ugliest and most destructive form of human group behaviour, racism. But we get nowhere by shutting our eyes. Differences will not fade away, and open-minded enquiry should help us to understand ‘why that person looks like that’ and why differences in physical appearance can be such a sensitive issue.

A common argument, introduced in the last chapter, is that after the various groups which are now spread over the huge Asian continent split up, they somehow drifted apart and ‘evolved’ in isolation from one another. As with the evidence for the unity of the original dispersal, there is genetic support for these ideas of isolation and change, but the archaeological and fossil support for the details of the story is less clear. The truth is that there is very little archaeological, let alone fossil evidence for where and when the ancestors of different modern Asian groups have been for most of the past 80,000 years, so, to a certain extent, any answer is speculative. Even with the uncertainty of fossil evidence, however, dates from

archaeological sites, combined with knowledge of past climate and the evidence from genetic markers, do allow us to reconstruct the routes taken by the first Asians. The pioneers penetrated their vast continent from three widely separated parts of the Asian Indo-Pacific coast. The choice of those routes had profound consequences for the subsequent physical differentiation of the explorers, resulting from isolation and adaptation to new environments.

Why is the question so fascinating – and anyway, what do we mean by ‘different’? The answer to the first is probably in our nature in that humans have evolved an extraordinary capacity for recognizing and remembering a large number of different faces. We need this skill partly because our extended social groups are large.

1

They are larger, and the interactions between their members are far more complex, than those of even our nearest living relatives, the chimpanzees. We

have

to be able to recognize many people. Failure to identify people you should know is embarrassing and is quickly noted as a weakness.

Along with the social advantages it provides, our ability to recognize faces enables us to classify what we see, and identify shared physical similarities within groups, and differences between one group and another. Clearly this can and does feed into our inclusive and exclusive group behaviour, and is what can lead us to discriminate against ‘outsiders’ who look ‘different’. Luckily our insight into our own innate tendency to ‘group and exclude’, and the terrible crimes against humanity that can result from organized racism, have led us to take statutory and voluntary steps to control and proscribe such behaviour. Tragically, these checks are not always successful, and old lessons of the evils of pogroms and group persecution are ignored, even by former victims of racism.

The limited power of words

A by-product of the fight against racism has been to render discussion of race taboo. Even the word ‘race’ itself, tainted forever by the

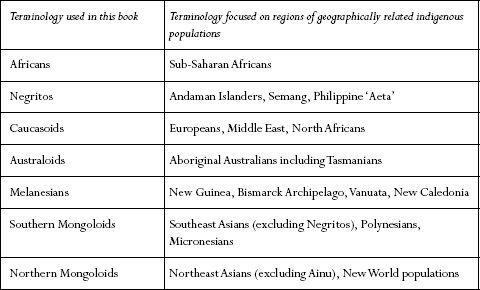

Nazi era, is outlawed by many anthropologists as unscientific, derogatory, meaningless, and giving the misleading impression that races are discrete entities when in fact variation, gradation, and admixture occur everywhere. This is all very worthy, but the fact remains – as children are quick to notice – that people from different regions can look dramatically different from one another. In the end, proscription and regularly changing euphemisms do not help; most alternative terms for race such as ‘population’ or ‘ethnic group’ are so vague as to be just as misleading. In this book I use terms such as ‘Caucasoid’, ‘Mongoloid’, and ‘Negrito’ to describe physical types, not because they are accurate but because they have common usage. Many anthropologists will object that they are derogatory and imprecise. From

Figure 5.1

, readers who share this view will be able to interpret my terminology in terms of their preferred emphasis on the geographical area of indigenous populations who appear broadly related on a wide range of biological attributes.

Figure 5.1

Table of rough terminology for ethnic groups and names/apparent racial differences.

With my choice of terminology I am not intending to derogate people who do not look like me – on the contrary, I know that the rest of the world has a distinct advantage in not looking like me. Equally, however, I believe that politically correct euphemisms are just as imprecise and misleading as the older terms. Inevitably, a well-known word such as ‘Mongoloid’ is often useful as a shorthand description of a general physical type, but we should always remember that the ‘traditional’ terms are imprecise descriptions of a complex biological reality that varies enormously within groups as well as overlapping between populations.

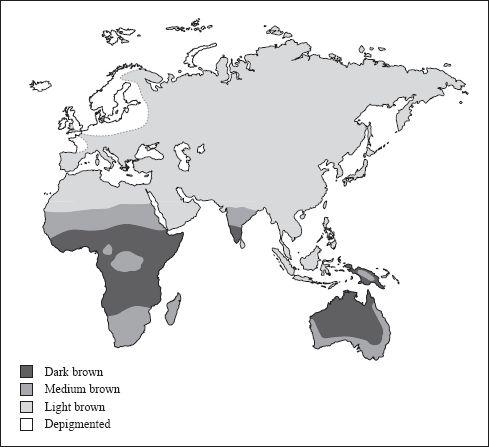

The most obvious physical difference between peoples of Eurasia is their skin colour, which tends to be darker in the sunnier tropical regions. This is no coincidence. Skin darkness, which depends on the pigment melanin, is controlled by a number of poorly understood genes and is also under evolutionary control. For those who live in tropical and subtropical regions, the risk of burns, blistering, and the likelihood of death from skin cancer induced by ultraviolet light is dramatically reduced by having dark skin. There are other, less dramatic advantages: for example, the melanin in pigmented skin allows it to radiate excess heat efficiently, as well as protecting against the destruction of folic acid, an essential vitamin. So in sunny climes, over many generations, people with dark skin live on average longer and have more successful families.

2

In North Asia (i.e. Asia north of the Tibet-Qinghai Plateau and east of the Urals) and Europe there is less sun and a lower risk of skin cancer, but there is the ever-present risk of rickets, a bone disease caused by lack of sunlight that was still killing London children even at the beginning of the twentieth century. I know this because I once did research on rickets while I was based at the Royal London Hospital’s pathology department. Rickets, or osteomalacia, came back in a small way to Britain in the second half of the twentieth century, but affected the children of families from the Indian subcontinent. Part of the reason

for this was their darker skin colour, which filtered out some of the already meagre sunshine.

So there are at least two evolutionary selection forces working in concert, tending to grade skin colour according to latitude. The sun-driven change in skin and hair colour evolves over many generations. From the available genetic evidence, Africans appear always to have been under intense selective pressure to remain dark-skinned. Outside Africa, though, we can see gradations of skin and hair colour as we move from Scandinavia in the north of Europe and Siberia in the north of Asia down to Italy and Southeast Asia in the south of those regions. The darkest-skinned groups of non-Africans still tend to live in sunny and tropical countries. Clearly, if change in skin colour takes many generations, we shall sometimes find people whose recent ancestors have moved to live in sunny countries and who are still fair skinned (and vice versa). A good example is Australia, a sunny country where the majority of today’s inhabitants are pale-skinned descendants of recent immigrants. Australia has one of the world’s highest rates of skin cancer, and this has already started it on the slow evolutionary path that will eventually lead to descendants of Europeans becoming generally darker-skinned. Conversely, the first visitors to the north of Europe and Asia probably started their journeys looking very dark skinned and evolved to become paler later. Apart from exceptions such as Australia, the average skin colour around the world is thus tuned to the relative amount of ultraviolet light (

Figure 5.2

).

3

Since this evolutionary trend continuously affects people of all latitudes at all times, our colour may have more to say about where our ancestors lived over the past 10,000–20,000 years than about their genetic divergence over the previous 60,000 years. So, the skin colours of today’s people are of limited value in tracing ancient routes of migration after the African exodus. In other words, colour is not the most useful marker for the understanding of human

prehistory between 80,000 and, say, 10,000 years ago. It may come as a surprise that skin colour is so evanescent, since it is the most obvious and divisive of all ‘racial’ characteristics. The key to human discriminatory behaviour is not in logic, however, but in the need to find an easily recognizable feature or pretext which unites our own group and excludes competing groups. The difference may be trivial. We regularly choose even more absurd differences, such as between closely related varieties of religion, to justify persecuting or killing our neighbours.