Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (30 page)

Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

Figure 5.2

Original distribution of skin colours in the Old World. With a few obvious exceptions such as Australia, the darkest-skinned groups still tend to live in sunny and tropical countries.

Changing face

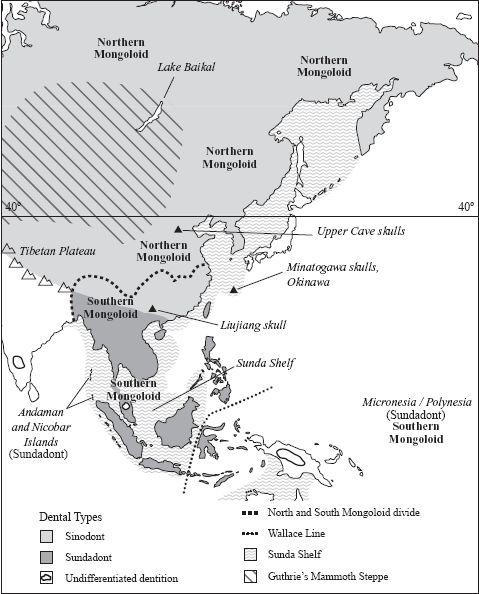

Other, more solid differences, such as the shape of our face, are determined by the underlying skull bones. These do vary between different parts of East, Southeast, and South Asia, and imply a rather long period of separation between the populations of these regions. Throughout East Asia we see the Mongoloid type (see

Plate 17

) with an extra, so-called epicanthic fold protecting the upper eyelid, and broad cheeks and skull. This type is often further divided into Northern Mongoloid and Southern Mongoloid, with the latter showing a less marked eye-fold and including southern Chinese and darker-skinned Mongoloid types in Southeast Asia (see

Figure 5.3

).

4

A great variety of peoples is found in South Asia, particularly in India. The majority of Indians, although dark skinned, are more similar physically to Europeans and Middle Easterners than they are to East Asians. Europeans, with their long, narrow heads, round eyes, and pale skin are sometimes called Caucasian. The farther north in India and Pakistan we go, the closer is the physical resemblance to ‘Caucasoid’ Levantines and Middle Easterners. In southern India, darker-skinned, curly haired, round-eyed peoples predominate. In eastern India, Assam, and Nepal there are peoples with a more Mongoloid appearance.

In

Chapter 4

we looked at another category of Asian peoples who may represent remnants of the original beachcombing trek to Australia. Scattered around the coast of the Indian Ocean, in Pakistan and India, and in the Andaman Islands, the Philippines, and Malaysia, are several so-called aboriginal groups who are superficially more reminiscent of Africans and New Guineans, because of their very dark skin and frizzy hair. These minorities have been called respectively Negroid, Negritos, and Melanesians.

Although they are just a tiny minority among the other Asian Old World peoples I have mentioned, such aboriginal groups have long

been regarded by scholars as physically somewhat nearer to the first out-of-Africa people than are the other Asians. This generalization effectively suggests that it is the bulk of the rest of Asia that has changed. A parallel dental study of the same aboriginal populations that I sampled for genetic markers (

Chapter 4

) has produced physical confirmation of this view. Another piece of evidence in favour of these aboriginal groups being relicts of the beachcomber trail is that the earliest fossil skulls from Europe and from East and Southeast Asia from before the last glaciation are not typically Caucasoid or Mongoloid in shape. Instead, we see forms closer to the oldest African and Levantine skulls of 100,000 years ago.

5

Earlier people were bigger and more rugged

How do we know what that first group of emigrants from Africa looked like in any case? The simple answer is that we do not. The reasonable and most parsimonious speculation, that they were dark-skinned and frizzy-haired, is based on the appearance of modern Africans,

6

although it is unlikely that Africans of 80,000–100,000 years ago looked quite like those of today. There are, however, some clues.

A few fossilized skulls of Anatomically Modern Humans have survived intact from around 100,000 years ago. One that is frequently referred to as characteristic of the period is from the failed first exodus to the Levant. It is named Skhul 5 after the cave where it was found. A number of other skulls were found in the same location – Skhul 5 was just one of the best preserved. A Skhul type was used to reconstruct the ‘face of Eve’ (see

Plate 18

) in our documentary film

The Real Eve

. Anatomically Modern Human skulls of this period show great variability, but they also share a few general characteristics that have changed in later populations, including modern Africans. Most obvious are the two closely related features of large size and ‘robusticity’. Robust features include large, craggy skulls, thick bones, and heavy brow-ridges when compared

with all today’s populations. The opposite of robust, ‘gracile’, is used to describe individuals with a flat, high, vertical forehead, smoother brow-ridges, and thinner long bones and skull bones. Other ancestral features of the time before the southern exodus include a relative narrowness of the skull (narrow breadth side to side compared with length front to back) and a broad upper face.

7

Size and robusticity of the skeleton are closely linked (especially in the skull). This presents us with a problem when we try to use bones to reconstruct prehistory, because the most marked change since the time of the African exodus has been a progressive reduction in size and robusticity in

all

peoples of the world,

including Africans

. Although some of the long-term change is probably genetic, the most dramatic size reductions have occurred within the past 10,000 years and may, paradoxically, be nutritional rather than genetic.

How did we get to be smaller?

Early hunter-gatherers led a tough, roaming life and therefore had a low population density, but their diet was rich in protein and minerals and varied in vegetables. Conversely, although the cereal farmers of the past 8,000 years may have had a high per-hectare crop yield and large families as a result of early weaning, their diet was monotonous – high in carbohydrate, and low in protein, vitamins, and calcium. Early weaning with high-carbohydrate, low-protein foods resulted in growth-stunting persisting into adult life. Consequently, although populations

expanded

with the advent of farming, child and adult size

decreased

dramatically. This effect is particularly marked in peoples eating rice without much animal protein, as in the Far East.

Today we can see the effect of reversing this form of cultural malnutrition. When East Asians migrate from a rice-eating culture to the USA and take on the low-bulk, high-calorie, protein-rich diet there, within two generations we see Asian children approaching the

size of American children. American and European populations, with their improved diet, have also seen a steady increase in adult size since the Second World War.

8

So, if robusticity depends partly on size, and the average size of today’s regional populations depends on their present diet, then the value of these two important determinants of our appearance in tracing the differentiation of non-Africans over the past 70,000–80,000 years is reduced. Also, many of the changes in robusticity, size, and general appearance of modern humans since the out-of-Africa migration could actually be reversible with a good diet and a healthy lifestyle. The rugged ‘Neanderthal’ look of some large players of contact sports can now be explained.

A couple of permanent changes can be observed over time, though: namely, in skulls and teeth. Reduction of skull size, to take that first, was caused by slightly different mechanisms in different regions.

Changing skulls

Although Australian aboriginals, and to a lesser extent some New Guineans, have undergone size reduction, they appear to have retained more of their skeletal robusticity than have nearly all other groups. The Australian skull reduction was both in length and breadth. Australian aboriginals are sometimes cited as the best examples of retention of the ancestral form, but, for several reasons, a better case could be made for New Guineans. A few details about the Australian aboriginals, past and present, remain unexplained – one is that the earliest fossil skulls from Australia were actually gracile, not robust. Another reason to regard the Australians as somewhat ‘changed’ from the ancestral type, perhaps as a result of admixture, is that most Australians today have curly rather than frizzy hair.

9

Only one other modern group has retained a similar degree of robusticity to Australians and New Guineans, namely the Tierra del

Fuegans of South America, and they are now practically extinct. In Japan another rather robust skull type is represented in the fossil record by the famous Minatogawa fossil skulls from Okinawa, a subtropical Japanese island, dated to the height of the last glaciation (see

Plate 20

). These skulls group by shape with the pre-Neolithic ancient Jomons of Japan, who are regarded as the ancestors of the modern aboriginal population of northern Japan, the Ainu. Among the ancestors of Europeans and Middle Easterners there was a limited and variable reduction in skull length and robusticity, leaving some degree of long skull shape (dolichocephaly) and also a variable retention of robusticity, which helps to explain my own beetle-brows.

10

It is in the peoples now called Mongoloid that the most marked changes occurred. The size reduction happened mainly by a marked shortening of the skull from back to front while retaining breadth and height. A further change that was characteristic of Mongoloid peoples was an exaggeration of facial flattening. This is most pronounced in Neolithic populations on the east coast of Lake Baikal in Siberia and around Mongolia (

Figure 5.3

). It is referred to as an exaggeration since facial flattening is not a new feature to the normal range of human variation. Facial flattening is also seen to a lesser extent in some early African skulls, in modern-day Khoisan hunter-gatherers, and in the revered founder-father of post-Apartheid South Africa. These changes resulted in the high, fine-featured, rather broad (brachycephalic) head shape now prevalent in East Asia, which is almost certainly genetically determined. East Asians are also among the most gracile of modern populations.

11

When and where did the physical changes characteristic of today’s Mongoloid populations occur? The date of the first modern human arrival in China is disputed, but may be around 70,000 years ago. It is important to remember that the first modern human inhabitants of China did not have a typical Mongoloid appearance, and that the few fossil skulls surviving from before the last ice age

20,000 years ago in lowland China and Southeast Asia had a robust, more ancestral form. In fact, the earliest undisputed Mongoloid remains anywhere in the world are dated only to within the last 10,000 years. Although these come from the Far East, the earliest human remains in Asia to have claims made for Mongoloid characteristics come from much further west at the site of Afontova Gora II on the Yenisei River in southern Siberia, to the west of Lake Baikal, and have been dated to 21,000 years ago. Since this is an isolated find of disputed significance, and there are no other preglacial skulls in southern Siberia to indicate a sequence, all that can be inferred from this scanty fossil record without reference to other evidence is that the location of the change towards Mongoloid features need not have been China.

12

The story of the teeth

Another, less striking but no less significant change was in tooth shape. The retention of several ancestral skeletal traits in modern Europeans is echoed in recent detailed dental research (

Figure 5.4

) which shows that Europeans can be grouped with the chain of remnant beachcomber populations around the Indian Ocean (including southern Indians, the Negrito Semang of Malaya, and New Guineans), who have retained more African ancestral dental and cranial features than other non-Africans. This remarkable long-distance dental link between Europeans and the other ‘least changed’ non-African groups of the Indian Ocean would be expected from a single southern exodus. To my mind, it is also another nail in the coffin (if any were needed) of racist stereotyping of Europeans as

advanced

and aboriginals as

primitive

.

13

Those ‘dentally undifferentiated beachcomber’ peoples are followed closely in the dental analysis by another cluster. It includes the non-Semang (non-Negrito) aboriginals of Southeast Asia, such as the Aboriginal Malay peoples of the Malay Peninsula, various remnant Pacific Rim populations such as the aboriginal Ainu in Japan,

and the Polynesians. These groups all share some features of an early, derived form of dentition, Sundadonty, so called after the Southeast Asian geological region of the Sunda shelf (Sundaland) where the type is proposed to have arisen. Sundadonty is not found any farther back west on the beachcombing trail, for instance in India. Importantly, most Sundadont populations also show some Mongoloid features and are classified as Southern Mongoloids. The Palaeolithic Minatogawas and Neolithic Jomons of Japan, who may be ancestral to the present-day Ainu, also share some dental features of Sundadonty with Southeast Asian and Pacific peoples.

14