Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (35 page)

Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

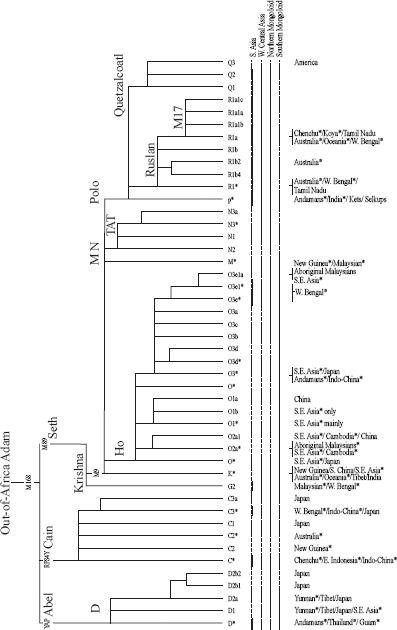

Figure 5.8

The Asian Y-chromosome tree. Note the almost complete separation between South Asia and Southeast Asians, except for overlap in tribals from West Bengal and shared root lines among all relict groups; also, unlike mtDNA, the near total separation of Northern vs. Southern Mongoloids, with latter dominated by Ho and former sharing lines extensively with South Asia and west Central Asia, particularly Polo derivatives.

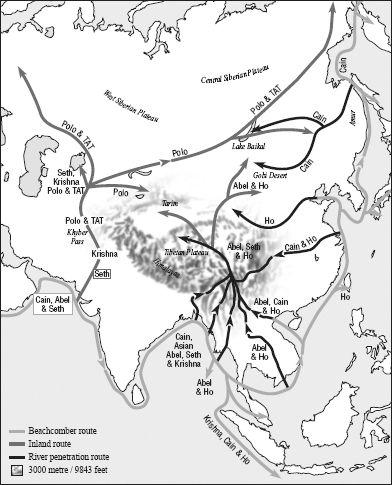

So, the first two male beachcombing founder clans used both of the eastern corridors to enter the Central Asian Steppe (

Figure 5.9

). Their final numerical contribution to world colonization was tiny compared with the third Adam branch, Seth, whose dominant seed spread to every corner of the non-African world and whose offspring eventually used all three routes to enter Central Asia. A recent survey showed Seth’s line accounting for 93 per cent of 12,127 Asians and Pacific islanders, with the descendants of Cain and Abel making up the rest. It is important to appreciate that, like the daughters of Out-of-Africa Eve, Nasreen and Manju, Seth travelled the coast road from Africa in company with

and at the same time as

his brothers Cain and Abel. He did not come out at a later time or by another route, as several geneticists have suggested. The evidence for this may be seen in the simultaneous presence of descendants of each of the three brothers, including specific Seth types, in relict beachcomber populations around the Indian Ocean, including those in Southeast Asia (see

Figure 5.9

).

44

It is Seth’s trail that confirms the alternative use of the third route – the northern trail into Central Asia round the west of the Himalayas (along with the more southerly beachcomber trails to Indo-China and round the eastern edge of the Himalayas). We can see where he started. Two-thirds of the world deep-branch diversity of this major founder Eurasian line is found in India. Seth represents a quarter of all Indian Y chromosomes, and his sons account for most of the rest.

45

Another 10 per cent of the Seth node is found in

Central Asia and, correspondingly, all four of his first-generation sons have significant Central Asian representatives, again suggesting the potential for direct spread north at the same time as the North Eurasian mitochondrial groups C, X, and Z around 40,000 years ago (see pp. 234–5).

We have seen that three of Seth’s sons were responsible for the colonization of much of India, Europe, the Middle East, and Mediterranean lands.

46

In this part of the story, however, we are not so much concerned with Seth and his three West Eurasian sons as with his fourth genetic son, Krishna, and the latter’s role in fathering the bulk of Eurasians not to mention nearly all Native Americans.

Krishna accounts for about 40 per cent of Y-chromosome types discovered so far. His wide distribution in Europe, Asia, the Pacific, and the Americas suggests that he was born in India very soon after the initial out-of-Africa dispersal. In spite of his early birth and the wide dissemination of his line, Krishna’s immediate sons have very discrete geographical distributions. Several are local to Pakistan and India, with some minor spread north to the Levant and Central Asia; another is found only in Melanesia (New Guinea and the surrounding islands); yet another (TAT) is exclusive to Central Asia and north-eastern Europe.

47

The two most prolific genetic sons of Krishna, however, are also by far the most dominant in terms of territory covered. They each illuminate the separate trails of the Palaeolithic peopling of Eurasia and America. One of these branches, Group O, is found nearly exclusively in East and Southeast Asia. I shall call this branch Ho, after both the Chinese explorer Admiral Cheng Ho and the revered Vietnamese nationalist hero Ho Chi Minh. If we imagine that this branch was born, like the maternal lines B and F, when a beach-combing Krishna arrived in Burma from India, then Ho splits easily into three branches. All three branches now have representatives in China, Indo-China, and Southeast Asia, but they differed in their degree of northern spread. One remained in southern China, Indo-China,

and Southeast Asia and still makes up 65 per cent of Malaysian aboriginal types. The second spread up the Pacific coast into southern China, although concentrating on Taiwan. The third spread much farther into China and north along the Chinese coast right up to Japan, Korea, and Northeast Asia, with a small amount of spread west along the Silk Road into Central Asia.

48

Notably, none of these three related East and Southeast Asian male branches ever made it to the Americas (see

Figure 5.9

).

In contrast to the East and Southeast Asian dominance of Ho, North and Central Asia and the Americas were to have their Y chromosomes supplied almost exclusively by the other major Asian son of Krishna – Polo (M45). The structure of Polo’s origin from Krishna in India (

Figure 5.8

) shows an early branch giving rise to Y markers and their offspring, who are still found among the former inhabitants of the Lake Baikal region (the Kets and Selkups). What is most exciting historically about this root is that it is the same son of Krishna who also gave rise to the westward influx into north-east Europe through Russia, thought to be associated with the Gravettian culture (see

Chapter 3

). We can now put all this together with the Upper Palaeolithic record of the Altai from 23,000 to 43,000 years ago, and with the story of the mitochondrial lineages of North and Central Asia. Polo would have arrived in Central Asia from Pakistan 40,000 years ago, and spread out in a giant ‘T’ formation, both east and west across the steppe – east to Lake Baikal and much later to America, and west into Russia and eastern Europe (see

Figure 5.9

).

49

We also have confirmation of this extraordinary twin distribution in the mitochondrial X marker in the Americas and Europe, and we have a genetic basis for the North Eurasian origins of the Native American mammoth culture, so eloquently implied by the title of a 1990s book,

From Kostenki to Clovis: Upper Paleolithic – Paleo-Indian Adaptations

.

50

A picture emerges of peoples moving north out of India and Pakistan to occupy the Russian Altai, coping with extraordinary environmental stress but reaping the rich rewards of big game. This North Asian founder population split east and west to occupy the great steppe. Those who went east eventually reached America, while those who went west contributed greatly to northern and western Europe. Those who stayed through the last great ice age shrank southward to refuges in Central Asia, and later re-expanded to become some of the Siberian and Uralic populations we see today.

Figure 5.9

First entry of Y-chromosome lines into Central Asia. As with mtDNA (

Figure 5.7

), the entry routes correspond with major Asian rivers. Seth’s grandsons Polo and TAT entered to the west of the Himalayas, dominating North Asia. The rest of East Asian Y lines entered from the Indo-Pacific coast, with Ho dominating China and Southeast Asia, and Cain further north.

We have seen how the early beachcombers could have split successively at various points on their journey round the Indo-Pacific coast and how, by 40,000 years ago, they had colonized most of Asia and the Antipodes. The first inland branch going north from India gave rise to the Upper Palaeolithic hunters of the Central Asian Steppe; later branches forging up the great rivers of Southeast Asia ultimately gave rise to a populations we now call Mongoloid. Evidence for so-called Mongoloid types, however, did not appear in Asia until the time of the last glacial maximum, around 20,000 years ago. So the forces that produced this physical divergence may have continued to build up for a long time after the first Asians arrived in North Asia. This leads us on to the next climatic phase of our story – the Great Freeze.

T

HE

G

REAT

F

REEZE

I

N THE LAST CHAPTER

we saw how East and Central Asia as a whole was peopled by a three-pronged pincer style of genetic colonization, starting originally from India. The oldest settlers followed the ancient beachcombing route right round the coast, from India through Indo-China and up north to Japan and Korea, leaving colonies as they went. From these coastal Asian colonies, pioneers penetrated the Central Asian heartland up the great Asian rivers through gaps in the huge east–west wall of mountains that flanks the Himalayas. South-east Tibet and the Qinghai Plateau may have been the first part of Central Asia to be breached 60,000 years ago, from Burma and Indo-China, while those who went up the Indus from Pakistan to the Russian Altai farther west settled during a mild period around 43,000 years ago. People who had reached northern China by the coastal route could have gone west up the Yellow River (the Huang He) into Central Asia around the same time or later.

The map of Northern Asia was now starting to fill up. By 30,000 years ago, a large swathe of the wooded southern part of the former Soviet Union (see

Figure 6.1a

), from the Russian Altai through Lake Baikal in southern Siberia to the Aldan River in the east, had been colonized by modern pioneers carrying a technology similar to that

of the contemporary European Upper Palaeolithic. Even the Arctic Circle was penetrated north of the Urals nearly 40,000 years ago. There is some evidence that the Upper Palaeolithic technology of North Eurasia may have travelled south to Inner Mongolia on a northern bend of the Yellow River, but on present evidence it seems that at this time such cultural influences spread no farther south into China.

1

Dale Guthrie’s vision of the hunter-gatherers wandering the great Asian Mammoth Steppe, stretching from eastern Siberia right across to Europe (see

Chapter 5

and

Figure 6.1a

), takes shape in the archaeological record of around 30,000 years ago. His prediction of the incipient ‘Mongoloid’ homeland in the southern Steppe is, however, highly speculative for this period and for Siberia. For a start, as mentioned, no indisputably Mongoloid remains have been found from such an early date. For all we know, those early southern Siberians could have looked like the Cro-Magnons of Europe. They shared a similar culture and, at least according to the story told us by the Y-chromosome lines, they shared genes with North Europeans (see

Chapter 5

). As evidence perhaps of a Western cultural centre of gravity, the first flowering of the mammoth culture at this time seems to have taken place much farther west, in Central and Eastern Europe (see

Plates 13

and

14

). Evidence for the mammoth culture seems to have reached Mal’ta near Lake Baikal only by perhaps 23,000 years ago (see

Plate 21

). This is just 2,000 years earlier than the first possible evidence of Mongoloid features from a little to the west of the same region of southern Siberia, at Afontova Gora.

2

The Big Freeze: ice, lakes, and deserts

As the Palaeolithic clock rolled on towards 20,000 years ago, however, events in the Earth’s spin axis and influences on its orbit hundreds of millions of kilometres away from our planet took tighter hold. Three great heavenly cycles of the solar system moved into a conjunction that ensured a minimum of the Sun’s heat reached

the northern hemisphere during summer.

3

The weather became colder, and the recurrent brief warm periods, or interstadials, which had characterized the period of 30,000–50,000 years ago, just stopped. It was these warm periods and their summer sunshine that had helped to melt the accumulated northern ice and prevent the ice caps from advancing across Scandinavia into Northern Europe. Now, the ice caps were able to expand in the north. The sea level started to fall again, eventually by 120 metres (400 feet). In short, the Earth was approaching its most recent ice age, or glaciation. (There had been quite a bit of ice on and off for the previous 100,000 years, and archaeologists tend to call the height of the Big Freeze the Last Glacial Maximum, or LGM for short, rather than an ice age.)