Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World (52 page)

Read Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World Online

Authors: Stephen Oppenheimer

Has evolution stopped?

Some geneticists argue that natural human evolution has stopped now that medicine allows the less fit to survive thanks to extraordinary advances in disease control and genetic interventions such as counselling and prenatal diagnosis. This seems absurd. Most of the world has limited access to such luxuries, and their influence on diversity of the world’s population as a whole is relatively small. Prenatal diagnosis is in any case intended mainly for single-gene disorders, causing life-threatening disease when inherited from both parents, sufferers from which would usually have had a major reproductive disadvantage if they had survived.

As long as we continue to die, during our fertile period, from diseases that can be affected in any way by our genes, evolutionary selection will continue to operate. Apart from infection, other killer diseases, which carry a genetic predisposition, such as cancers are unaccountably on the increase. Male sperm count is also falling. While these pressures may result from chemical pollution of our environment and food, our susceptibility to them varies and is again

genetically

determined. As far as human biological evolution is concerned, it has not stopped, merely slowed down.

In the end, humans are the products of the same evolutionary forces as all other animals and will continue to be so. Hopefully, we will come to appreciate this before it is too late. We might even lose our species’ arrogance and accept that we share a thin smear on the surface of a small planet and depend more on our non-human colleagues than many of them depend on us for survival. Only then can we allow our world to recover from the damage caused by our success.

My son once asked me whether a new species of human will evolve – or be artificially evolved. Well, the standard parental answer was that ‘it depends’. I guess it will depend immediately on what our various cultures drive us to do to ourselves and to our environment. Our aggressive behaviour, aided by the demands our growing populations make on our environment, give us the unwanted capacity to impose stress or even to extinguish our species. Our white-hot modern technology would not be able to burn an escape hole from the impoverished prison our small planet might become for the majority of its inhabitants. How we adapt to our fouled nest, and avoid fouling it further, again depends on our immediate capacity to evolve our culture. If we do survive another near-extinction, self-imposed or otherwise, our successors may be biologically different, but there is no doubt that they will be culturally different.

A

PPENDIX

1:

T

HE REAL DAUGHTERS OF

E

VE

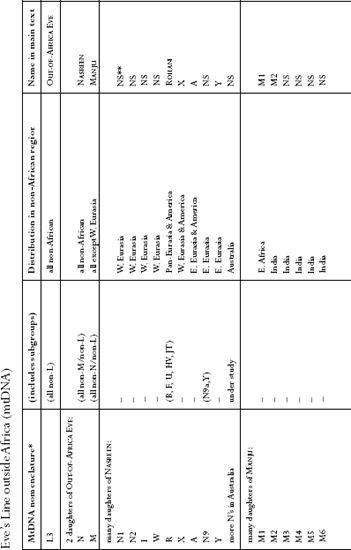

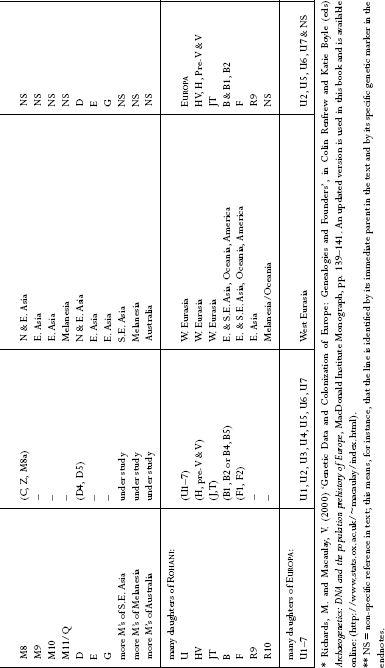

The two following pages

: Names used for mtDNA lines. This table is intended as a quick reference to naming conventions of the commoner mtDNA lines outside Africa used in the text.

Pages

368

and

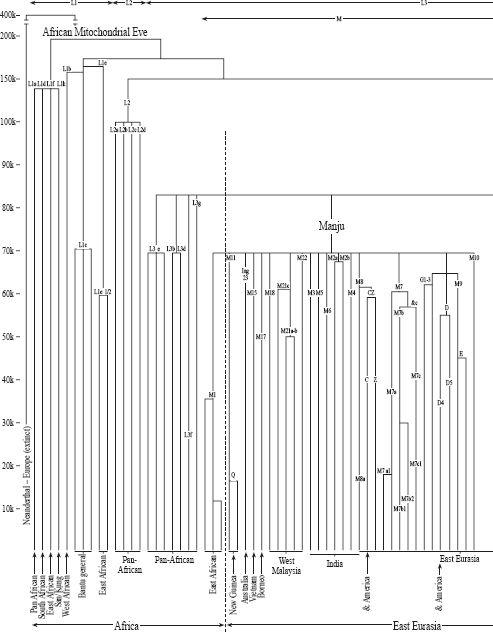

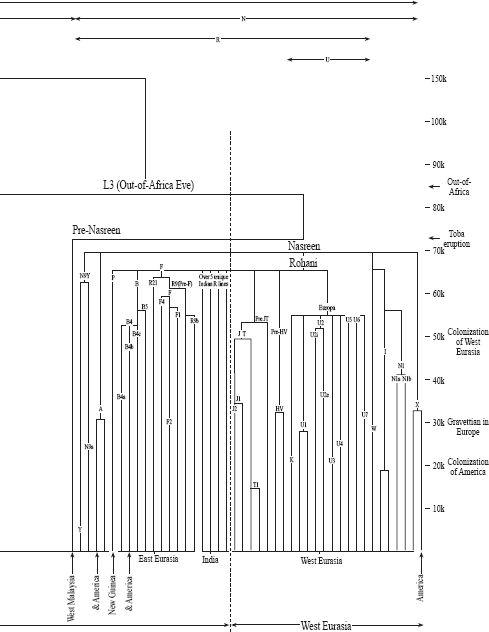

369

: The full world mtDNA tree. Mitochondrial Eve ultimately has many daughters. The oldest branch is around 190,000 years. All non-African branches derive from two daughters, Manju and Nasreen, of L3 (Out-of-Africa Eve) who dates from 83,000 years ago. From 70,000 years ago there was a worldwide dramatic increase in daughter branches, occurring after the great Toba volcanic eruption. Specific regional distribution is shown at the foot of branches. (Branch dating by the author, where possible using complete sequence data; see

Chapter 1

22

).

A

PPENDIX

2:

T

HE SONS OF

A

DAM

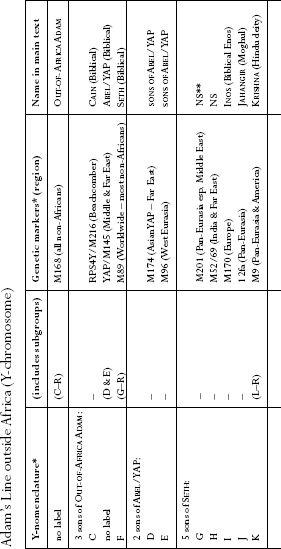

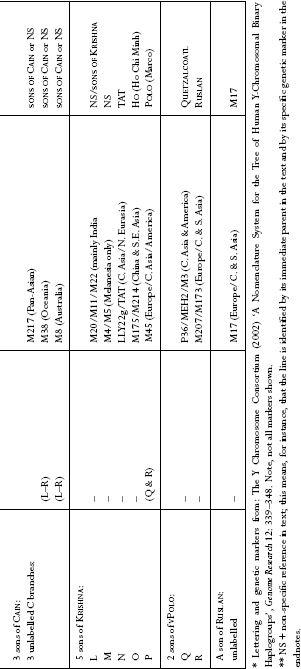

The two following pages

: Names used for Y-chromosome lines. This table is intended as a quick reference to naming conventions of the commoner Y-chromosome lines outside Africa used in the text.

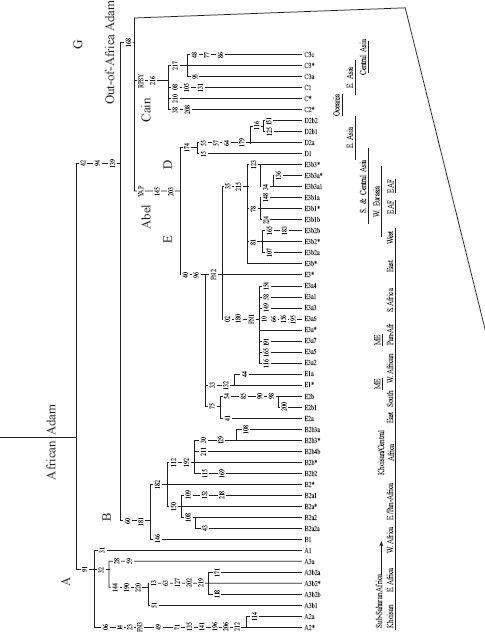

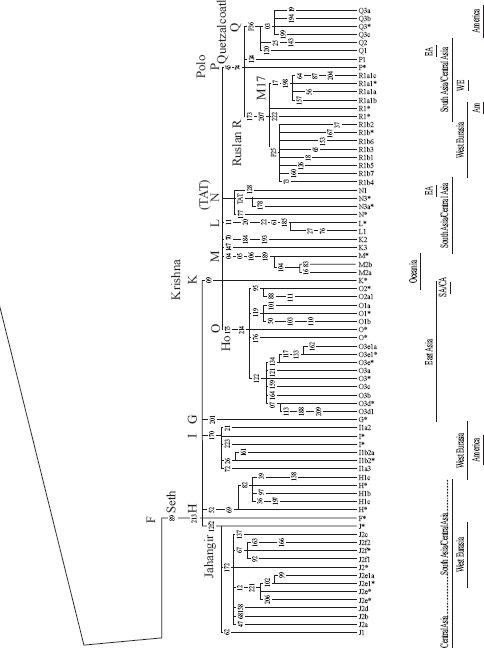

Pages 374 and 375

: The world Y-chromosome tree. African Adam ultimately had at least as many sons as African Eve had daughters. All non-African branches derive from M168, the Out-of-Africa Adam and his three sons Cain, Abel and Seth. Specific regional distribution and nomenclature are shown at the foot of branches. Branch dating is not shown since there is no consensus on method or calibration. The Y-tree shown here is a fusion of Underhill et al. 2000 [

Chapter 1

3

] and the Y Chromosome Consortium [Prologue

37

].

N

OTES

These notes are intended as a facility to readers, academic or otherwise, seeking technical clarification and sources of evidence. They contain technical terms and detail which, in the space available, cannot be explained to the same level as in the main text. Multiple citations are merged at the end of a paragraph in many cases, to reduce total numbers of notes. In these cases each citation is keyed by a relevant text string (in bold).

Preface

1.

Cann, R.L. et al. (1987) ‘Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution’

Nature

325

: 31–36; Vigilant, L. et al. (1991) ‘African populations and the evolution of human mitochondrial DNA’

Science

253

: 1503–7; Watson, E. et al. (1997) ‘Mitochondrial footprints of human expansions in Africa’

American Journal of Human Genetics

61

: 691–704.

2.

Richards, M. et al. (2000) ‘Tracing European founder lineages in the Near Eastern mitochondrial gene pool’

American Journal of Human Genetics

67

: 1251–76.

3.

That story was told in S. Oppenheimer (1998)

Eden in the East

(Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London); see also: Oppenheimer, S.J. and Richards, M. (2001) ‘Fast trains, slow boats, and the ancestry of the Polynesian islanders’

Science Progress

84

(3): 157–81.