Out of India

Authors: Michael Foss

Five Romantic Poets

The Royal Fusiliers

The Founding of the Jesuits

The Age of Patronage

Tudor Portraits

Undreamed Shores

Chivalry

Traditional Nursery Rhymes

Folk Tales of the British Isles

The Children’s Songbook

(with John White)

The Borgias

(under the pseudonym ‘Marion Johnson’)

The Real West

Treasury of Nursery Rhymes

*

Treasury of Fairy Tales

*

Looking for the Last Big Tree

(fiction)*

Beyond the Black Stump

*

On Tour: The British Traveller in Europe

*

Poetry of the World Wars

*

The Greek Myths

(under the pseudonym ‘Michael Johnson’)

Gods and Heroes: The Story of Greek Mythology

*

The World of Camelot

*

Celtic Myths and Legends

*

People of the First Crusade

*

The Search for Cleopatra

(in association with BBC

Timewatch

)*

*Published by Michael O’Mara Books Limited

First published in Great Britain in 2001 by

Michael O’Mara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

This electronic edition published in 2012

ISBN: 978-1-843178279 in ePub format

ISBN: 978-1-843178262 in Mobipocket format

ISBN: 978-1-843178060 in hardback print format

Copyright © Michael Foss 2001

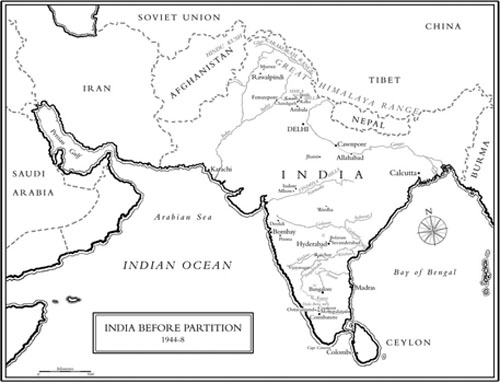

Map copyright © Michael O’Mara Books Limited 2001

The right of Michael Foss to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Every reasonable effort has been made to acknowledge all copyright holders. Any errors or omissions that may have occurred are inadvertent, and anyone with any copyright queries is invited to write to the publishers, so that a full acknowledgement may be included in subsequent editions of this work.

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover design by 875 design

Cover photograph by Glen Allison © Stone

Designed and typeset by SX Composing DTP, Rayleigh, Essex

Ebook compilation by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk

CHAPTER ONE

A Child’s View of the Ocean

CHAPTER FIVE

A Brief Introduction to Magic

CHAPTER SEVEN

A Hush in the Hostel

CHAPTER EIGHT

Interrupted Lessons

CHAPTER TEN

Blue Hills of the South

CHAPTER ELEVEN

In Churchill’s House

M

ICHAEL

F

OSS

March 2001

ROLOGUE

WHAT HAVE I LEARNT?

S

OME TIME AGO I saw a picture on the back page of one of our national newspapers. It was a photo that had nothing to do with news or comment but was an artistic image indicating, I suppose, the respectable culture of the paper. The picture showed flooded land in India towards the end of the monsoon season, when the rising waters form temporary

jheels

or shallow lakes in the long hot flats of the plain give to a land of too much desolation and dust the momentary charm of lakes and islands. Some water buffaloes were wallowing in this unexpected playground, their glistening black backs and the large sweep of their horns standing out just above the level of the water. A thin, barefoot boy in shorts and a loose cotton shirt was leaping from the back of one buffalo to another. The camera had caught him in mid-air, in an act of the utmost grace and agility. It was a picture of pure joy.

As I looked at it I thought I had never seen such a representation of an ideal childhood, a life so in tune with a particular place and time.

The boy in the photo was some ten or eleven years old, about the age that I was when I left India.

*

I hardly knew my father when I was young, since by profession he was a soldier and naturally had serious business to attend to in the early years of my life. Later

perhaps I no longer wished to know him too well. I had never formed the habit of him and then it was too easy to drift away. Wartime separation, then boarding school, holidays apart from my parents abroad, a home quickly abandoned for a student apprenticeship, and then a flight to new lessons of the world and more hopeful skies – what chance did I have to overcome the shyness that crippled both of us, and the mutual suspicion of fathers and sons? When he died, an old man gasping from emphysema, trying to find bearings amid the scrabbled memories of Alzheimer’s disease, there was, after the small griefs of the leave-taking, if not nothing, at least very little. I wondered at my … what? Unfilial coldness? Lack of charity? An impediment of the heart? He left me no keepsakes; but his watch, which remained unclaimed, came into my possession. In a similar casual manner, as if dropped behind in the fitful passage to quite another destiny, I found in my hands a large photograph album. I have been going through this album recently, again and again, trying to find the true tracks of early wanderings half-remembered, half-understood.

The photos dated from a period shortly before the First World War, pictures of an Anglo-Indian world ten to fifteen years before my father came to know it. The photos were large prints, the work of a professional photographer whom I assume to have been an Englishman. Large compositions, at that time, demanded some technical dexterity, and portraiture of the Raj also required tact and a proper sense of the rightness of things. The task was not lightly entrusted to Indians. So I imagine the photographer, a civilian tradesman deferential perhaps in the presence of so much military brass, in Norfolk jacket and plus-fours, his head ducking in and out from beneath the green baize cloth that covered the bellows of the box camera. He was in any case a competent man. His pictures came out clear and sharp and well-composed, many in the

sepia tint that always lends nostalgia to the most ordinary of everyday events.

Most of the photos were of regimental groups and places, or views of Indian towns and landscapes, particularly on the mountainous north-western borders fronting onto Afghanistan. There were confident group portraits of the English officers and the Indian subadars and jemadars of the 57th Frontier Force. This was the regiment known as Wilde’s Rifles, which my father later joined. There were views of the town and the hills and the Army Signalling Station at Kasauli, in the foothills of the Himalayas. There were views of Peshawar and the bleak eroded mountains and the little lonely hill stations beyond, at the limit of safety, in the harsh wilderness that the regiments of the Indian Army Frontier Force were supposed to keep secure for civilization against the Pathans of the hills, those inveterate brigands and disturbers of all colonial peace. Then there were flat vistas of the Indus plain, an expanse so vast and empty that it was in its own way as cheerless and intimidating as the mountains themselves. And lastly, in a big group, there were numerous photographs of the great Indian durbar that took place in Delhi in 1911.

It seems to me that some huge matters were implicit in those images. A powerful moment in history, if only I could catch it. Again and again I turn over the pages of these photos, drawn to the scenes of that durbar.

From all over British India the soldiers and the administrators of the Raj had collected to do honour to the King-Emperor (such a title for that middle-aged gent in a tight coat, with his bug-eyed Hanoverian stare hardly humanized by a bluff sailor’s beard!). The photographer had taken many pictures by day and by night, of the temporary military encampments around Delhi. By day, ranks of empty army tents, squared-off in the straight lines beloved of the military mind, were strung out amid the yellowing

grass, the scrub and the low trees on the edge of the Old City of Delhi. It looked as if the city was encompassed by the lines of an invading army. An enemy was penned within. By night, under the flare of petroleum lamps, the pale forms of the tents looked ghostly and alien, a sublunary world full of menace.

Inside this ring of tents a Moghul gate to the Old City, ablaze with floodlight, was hung with a giant picture of George V and carried across the main arch, in very large English letters, the legend

LONG LIVE THE KING-EMPEROR

. I wondered at the effrontery of this message, smack in the face of a teeming oriental city that spoke many local languages but where only the clerks and the well-heeled could have read English. The message, quite obviously, was one of self-satisfaction directed elsewhere than at the Indian population.

On the field of the durbar a square dais with many slender columns was topped by a gilded onion-dome, under which the King-Emperor was seated. The effect was not fortunate. Here East and West jostled, and the Brighton Pavilion came to mind rather than the court of Akbar. At the foot of the dais Indian soldiers in dark uniforms and white topees guarded a compound marked off by a velvet rope. Indian princes and high officials in their best ceremonial robes looked on from a small but sufficient distance. The impression was of a sunny day at a Royal Ascot race-meeting. Several of the high-ranking men – I could see no women in this enclosure – were sheltering from the sun under black umbrellas more often seen in a London winter. Around the important people was an empty space. Then the mass of spectators sat in a broad circle under an awning striped like circus canvas. All these spectators were Europeans, the men in uniforms as spick and span as braid, polish and brass could make them, and the women in iridescent silks and feathers looking as flighty as a flock of Himalayan pheasants.