Oxfordshire Folktales (10 page)

Read Oxfordshire Folktales Online

Authors: Kevan Manwaring

F

RIDESWIDE

AND

THE

T

REACLE

W

ELL

Frideswide was renowned for her beauty, but she had hoped to escape the unwanted attention of men when she took the veil –retreating from the world behind the walls of the convent at Oxford.

Alas, this was not to be, for word of her legendary beauty reached the ears of Aelfgar, King of Mercia. The fact she was a nun did not put him off. He set out to behold her beauty himself. He camped outside the convent with his rough and ready army, and waited. It was clear that the slavering bunch of heathens would not restrain themselves for long – not with such rich pickings at hand. Rather than risk bringing ruin upon the convent, Frideswide fled. Scenting the thrill of the hunt, Aelfgar pursued her with renewed vigour – alone – into the wild wood which grew beyond the water meadows.

Heart thudding in her chest, Frideswide darted through the trees like a deer pursued by a pack of hounds; until she found her way blocked by a thickly flowing stream. She cried out in dismay. As her pursuer approached, she fell to her knees to pray.

Aelfgar snorted like a boar, stroking his beard as he approached. He had run his quarry to ground.

‘Odin’s blood, woman! I am not used to being denied. You gave me a hearty chase, but now – where is my reward?’ Suddenly, a blinding pain shot through Aelfgar’s eyes and he doubled over in agony. ‘Aargh! What witchery is this?’ Aelfgar raised his hands before him. The woods, the woods were dark…

The gods deemed fit to punish him in his lusty pursuit, striking him blind! He howled with rage as he stumbled over roots and bumped painfully into branches and trunks.

Rather than take advantage of this stroke of divine luck, Frideswide took pity on the afflicted King and turned back to help him. She prayed to Saint Margaret – and miraculously a spring bubbled up. Frideswide cupped some of the clear water in her hand and bathed the eyes of the King. Suddenly, his sight was restored by this ‘treacle’; this healing fluid.

Aelfgar was a changed man – the scales, as they say, fell from his eyes and he saw the error of his ways, renouncing any designs on Frideswide and his heathen faith. The King turned to the God of Christ and Frideswide was allowed to return to her convent, her chastity intact. She dwelled there in peace for the remainder of her days, building a small chapel by the well, which would one day become the present church of the parish.

The legend of Binsey’s treacle well grew over the centuries as the dreaming spires of Oxford became a venerable seat of learning. Yet, even in such a place, folly persisted. Waggish Oxford undergraduates would send gullible tourists to search for the village’s famous treacle well and treacle mines. At least the former had some credence – it was Frideswide’s healing well. The latter could perhaps be imagined to be the nearby shallow ponds in the summer, covered with a thick yellow slime.

The treacle well became neglected through time, its source choked with weeds. This dismal state of affairs continued to the point when, in 1850, a visitor declared that the well had been lost. Local folk claimed to know nothing about it.

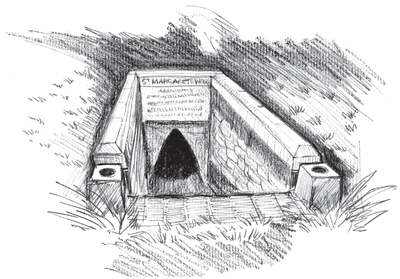

Fortunately, in 1857, a local vicar, Reverend Thomas Prout, a don of Christ Church, rediscovered it and restored it by 1874, with a protective archway and stone steps, with a clear inscription dedicating it to St Margaret.

Countless pilgrims have sought it ever since as a cure for eye complaints and other bodily disorders, yet it has also been a source of inspiration – an Oxfordshire Mimir. If this seems fanciful, then consider its mythic status in English literature…

One idyllic afternoon in 1862, the Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson rowed towards Godstow with his friend Robinson Duckworth and three guests – Lorina, Alice and Edith Liddell, the young daughters of the Dean of Christchurch. To pass the time, the girls asked for a story and Dodgson happily obliged, conjuring a tale of three children – Elsie, Lacie and Tillie – who lived at the bottom of the treacle well.

The story so delighted the girls that the Reverend was encouraged to write it down – which he did under his pen name, Lewis Carroll – and

Alice in Wonderland

was born. Frideswide’s treacle well became a rabbit hole and its magical properties took on a completely different dimension.

![]()

The well has gained an extra significance now, as the inspiration for Lewis Carrol’s children’s classic. Near the well, within the peaceful churchyard, there is a grave decorated with stone roses dedicated to Mary Ann Prickett. The governess of Dean Liddell’s children, she was the inspiration for the Red Queen (nicknamed ‘Pricks’ by the children). It is a curious coincidence that Thornbury is the old Saxon name for the site.

When I went to visit the famous well, it took some finding – I had to ask directions at the local inn, The Perch. The friendly French barman was very helpful and said that the well was ‘very special’ and that the best time to see it was during an eclipse, when the water became ‘thicker’. Finally locating it, I was delighted by the picturesque setting – a small isolated chapel with a congregation of goats. There was evidence of veneration: withered flowers; a card; and a little fairy statuette. I fished a pen out of the viscous yellowy water, low within its chamber: the ultimate ink-well. Sitting on a wooden seat carved from a stump, I contemplated the ‘stickiness’ of such places. It is fascinating how one narrative can inspire another, and how this accretion of narrative can draw visitors to a place, and enrich their perception of it, so that it is experienced with a ‘mythic filter’.

How many more ‘rabbit holes’ have been inspired by Lewis? It has become a familiar point of reference in popular culture: for example in the film

The Matrix

, Neo is asked, ‘How far down the rabbit hole do you want to go?’

What would St Frideswide make of it all? From Aelfgar to Alice, the Treacle Well has continued to flow – long may it do so.

S

PANISH

W

ATER

‘The rain in Spain falls mainly on the plain…’ Lucy recited this to herself as she made her way, old milk bottle in hand, along with her friends and fellow villagers from Leafield, to the magic spring. The spring had been venerated in Wychwood by the folk of the forest for as long as anyone could remember. A good spirit was said to reside in it – as long as it was kept sweet – which could heal folk of all kinds of ailments: from eye to heart; from back to bowels.

It was Easter Monday, and they were off to make ‘Spanish Water’. Lucy, the new girl in the village, felt a bit embarrassed, because everyone seemed to know what this meant except her. When she had asked her friends they had giggled, as though it was obvious and she shouldn’t be so foolish.

The bluebells were out and carpeted the floor of the forest either side of the track. The clean Spring sunlight pierced the tangled canopy, budding with new growth. Lucy had always lived in the forest, although only in Leafield for less than year, and found the presence of trees comforting. They seemed to sing to her as she walked to and from school; as she played with her friends; as she sat with her Gran on her porch – they were the constant soundtrack of her life. She knew there was a big wide world out there – she was quite good at geography and could list the capitals of Europe; even knew a little bit of French and German – but she had never gone beyond Oxford, which had seemed like a teeming metropolis to her when she had visited it with her father once. She had developed neck-ache from looking up so much at the dreaming spires, which seemed to stretch to Heaven. They visited one of the churches, St Giles, and its fluted vaults seemed to mirror a forest grove in stone.

Yet it was in Wychwood that she felt a true presence, though of what exactly she couldn’t say. This was her place of worship, where she often felt something – ancient, deep and sacred – in the wood, in the soil, in the stone. It was in her bones. And today she wasn’t alone, at least a hundred of the villagers processed to the old well, with their bottles, led by the local priest, Reverend Hartlake. In their Sunday best they made an odd sight walking through the forest in solemn silence. It was like some kind of dream.

They passed Hatching Hill and Maple Hill; the long barrows between Slatepits and Churchill Copse; until they came to the small stone trough, half covered with a thicket and dripping with moss. There, from a little gap, the glittering water trickled out.

The priest stepped onto a stone next to it and the parishioners bowed their heads in prayer. Reverend Hartlake was canny and knew he could not stop the villagers from continuing this questionable tradition, so he had made a point for many years now of coming along with them and giving it his official blessing.

One by one they filled up their bottles, which took some time, but nobody seemed to be in a rush. When Lucy was finished she held the glass bottle up and it seemed to catch the sunlight – until the next in line coughed, and she moved on to make room.

And then, holding their glass, now cool and dappled with droplets, they sang hymns praising the risen Christ. Reverend Hartlake talked about the ‘Water of Life’ and how it should always be shared. Then the formal part was over and freshly baked Easter biscuits were offered around – folk picnicked in small groups, breaking bread amid the green.

Then Old Bliss the Teller settled down on a stump and told them a strange story, how once in the land travellers were offered refreshing draughts from wells, such as this one they sat next to, by maidens with cups of gold. Until one day a greedy king, Amangons, wanted the cup, the water and the maiden for himself. He took by force what had been given freely. His knights followed suit, despoiling the other maidens and desecrating their wells. Amangons had his cup of gold – but at what cost? He retired to his castle where he became ill – his maiden could not help him. He could not die or get better, but lived on and on, becoming the Fisher King. The land became a wasteland, the wells were abandoned and no traveller was offered a cup of gold any more.

Old Bliss lit his pipe and sat back, contemplating a smoke ring.

‘Is that it?’ asked Lucy, disappointed by the ending.

‘Oh no, young missy! That’s not the end of it by a long chalk. Then a young knight came, from a distant land, pure of heart, who, upon hearing about the Fisher King, decided to go and help. He journeyed to his castle, and, finding it and the King in a terrible state, he set to make things better. Amangons withered away on his throne, coughing and groaning with no one to serve or care for him. The knight felt compassion in his heart. ‘Your Majesty, what ails thee?’ he asked. The King coughed hoarsely and weakly gestured for a cup. The knight found an old golden goblet, gave it a wipe with the sleeve of his tunic and filled it with good clean water from his own waterskin, before offering it to the King. Amangons stretched out a shaking hand and slowly, painfully, drank it. He immediately felt better, the light returning to his eyes. He looked upon the good knight and smiled, saying: ‘The Grail is in the giving; not the taking.’ The Fisher King was healed and the land laid waste no more.