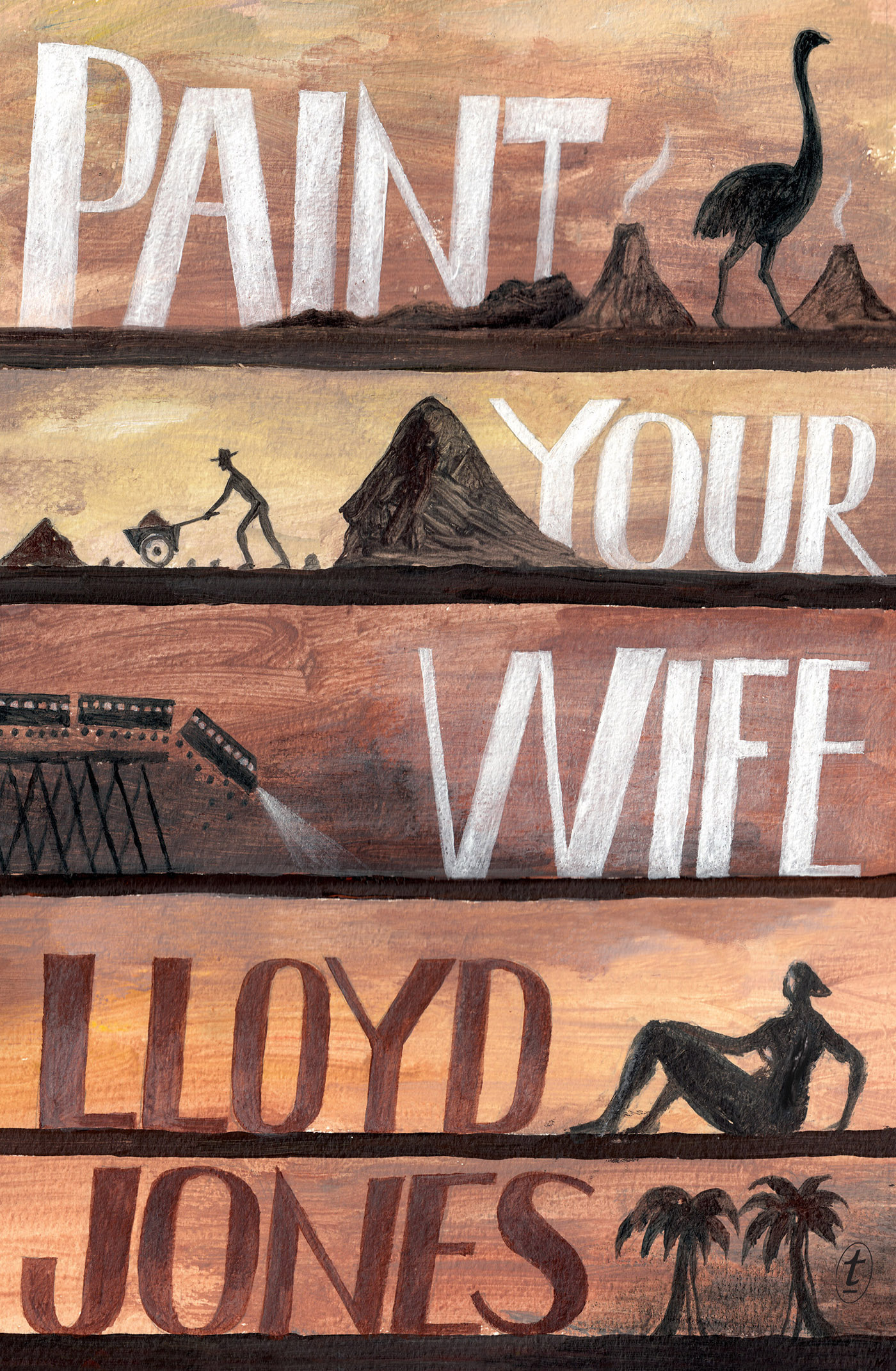

Paint Your Wife

Authors: Lloyd Jones

Lloyd Jones was born in New Zealand in 1955. His best-known works include

Mister

Pip

, winner of the Commonwealth Writers' Prize and shortlisted for the Man Booker

Prize,

The Book of Fame

, winner of numerous literary awards,

Hand Me Down World

and

his acclaimed memoir,

A History of Silence

.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © Lloyd Jones 2004

The moral right of Lloyd Jones to be identified as the author of this work has been

asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of

this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system,

or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner

and the publisher of this book.

First published by Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, 2004

This edition published by The Text Publishing Company, 2014

Book design & illustrations by W. H. Chong

Typeset by Midland Typesetting

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Creator: Jones, Lloyd, 1955â author.

Title: Paint your wife / by Lloyd Jones.

ISBN: 9781925095371 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781922182395 (ebook)

Subjects: PaintersâFiction.

Dewey Number: NZ823.2

Contents

I've been visiting our son Adrian in London. He is a year or two older than I was

the first time I flew there, dropping out of the clouds, glancing down at the storybook

burst of Westminster and the serpentine crawl of the Thames. This time around it's

been ten days of lounging about, filling in time reading the newspapers, musing on

the crazy things that happen out there in the world. Hungry car thieves in Sao Paulo

mistake AIDS-infected blood for raspberry jelly. That sort of thing. I was enjoying

myself and London was big and scrambling. I showed up in the shop windows as a smiling

amiable fellow, someone I hardly ever am at home. There were the same row houses

in their grainy white that captured my interest more than twenty years ago as a

newly graduated paint technician. London seemed to be painted in the colours of mist.

The contrast with home was striking. Our houses were like bright coloured marbles

let loose over the plain, shining down from hillsides, beaming up at the broad sky.

More importantly, our paint was guaranteed not to blister or peel, to withstand extreme

conditions. Our white was a cat's-eye white.

Opaque, unpleasant to touch. London's

white was creamy; its grime charmed.

This time London had never looked so green. The weather was brilliant. Blue skies,

the pavements hard and cheerful. I spent much of my time walking and looking for

a park bench on which to sit and open my paper. St James's Park. Holland Park. Hyde

Park. Squirrels running up trunks. Foreign nannies with prams. Boys and girls tongue-kissing

over the rolling park grass.

Around six I'd totter off to some pub or bar rendezvous suggested by Adrian. He'd

ask me what I got up to that day and I might begin to tell him about âThieves in

Sao Pauloâ¦' But he was only interested to know if I'd visited any of the second-hand

shops.

âIf you were over near Portobello Road you could have looked up Mr Musty at least.

I was in there the other day and said you might drop by.'

I had to shake my head and look away guiltily. âAfraid not. Ran out of time.'

Adrian seemed put out. I knew he'd gone to some trouble to look up these places.

âAnyway, the man to ask for in Musty's is Dave somebody. Ginger hair. Missing his

little finger.'

I gave a vague nod of intent.

âYou should, you know.'

âI know I should but I didn't. I ran out of time.'

Just what did I do? I read the newspaper and ordered another cup of tea or looked

for my ref lection in the passing shop windows. Names floated up from the past.

Assorted paint arcana.

In paint tech we used to have a teacher we all liked because he played in a rock

band at weekends. He was entirely bald, apart from a pair of rimless glasses. When

he smiled it was from a position of unrealised advantage. Our paint, he liked to

say, could stand up to the most testing of conditionsâsearing heat, freezing rain,

salt winds. London's paint by comparison would turn to omelette. He said this a lot

and whenever he did we would exchange triumphant smiles.

It'd all turn to omelette.

We loved saying that.

âJohn Ryder. That's it. I knew his name would come to me.' Adrian looked unimpressed.

He doesn't know about the paint tech side of me. When he was born I'd given up paint

for trade in second-hand goods and furnishings. He looked at the dregs in his glass

and drained them.

One night he said he wanted to take me clubbing. I scratched around for a reason

why this wouldn't be possible. I asked where he had in mind and he said in his new

way of speaking, his eyes and face angling off to new arrivals entering the bar,

âDoesn't matter where. Trust me. You'll love it.'

I ended up paying an exorbitant taxi fare. Twenty years ago it had been enough to

walk

everywhere,

and with holes in my shoes. I didn't dream of catching a cab, anywhere.

Adrian

and

his mates seemed unfazed. They all work in the film industryâAdrian said

what

they

did but I can't remember; strange-sounding job descriptions, grippers,

line

people.

They probably catch cabs every day of their lives. On the other hand

I

paid

an amount which in my daily trade in second-hand furnishings was worth a decent

sofa

and

maybe a mattress thrown in. But as I say, Adrian and his mates seemed so

remarkably

cool

about it that I hated to make a fuss. Instead

I followed them through the doors manned

by Nigerians in black leather jackets. They nodded at Adrian but seemed puzzled by

me. I couldn't hear a thing. I gather Adie was explaining, his thumb hooked back

in my direction, while the Nigerian's face hung low to catch the drift. He nodded

at the floor and I passed by his uplifted red eyes. Inside it was a deafening

thump

thump thump.

I had to yell for Adrian to hear.

The price of the drinks was out of this world. It was beers all round for which I

paid after stupidly saying âLet me,' which they did. I paid for another round, and

another one after that, until at last they slipped off the feeding teat and disappeared

into the crowd of bobbing heads. I followed the arrows to something promisingly called

âthe conversation pit' where indeed I had a conversation with a black woman along

the lines of, âYou're black,' to which she smiled patiently and said, âYes. Thank

you. I know.' It wasn't so horribly gauche as that, but not all that far behind either.

I asked her where she was from. She leant her head closer so as to hear and I could

smell all kinds of tropical fruit smells. I said, âAre you from Guyana?' and she

shook her head and her big luscious mouth fell open; she said, âNo, darling, I'm

from around here. Born here, Harry Bryant,' she said. I liked the way she said âHarry

Bryant'.

After some more fumbling of this kind we did manage a conversation. We asked about

each other. We were even going to dance but we didn't in the end. Eventually I used

up all my goodwill and her patience and after saying decently, âWell Mister Mayor,

it's been nice meeting you,' she moved off stylishly, holding her glass with both

hands before her, a whiff of tropical breeze cutting through the thick air. Across

the room

of dancing shadows and shaven heads there was my son grinning back at me.

I don't remember much more of the night. That nice black Brixton woman was the last

decent conversation I had. The rest of the time was filled with noise and beer. And

shots of something in tiny glasses that was painless and irresistible at the time.

I don't recall how we made our way back to Adie's flat; I hope there was a taxi, I

hope no one drove, but that's where I woke feeling just bloody terrible, in a sickly

sweat. The conversation with the nice black woman from âround here' played endlessly

back in my head with a clarity that was cruel and mocking.

I got dressed and slipped out of the flat and drifted to the nearest underground station.

I rose gastrically near St James's Park to warm sunny skies. Flirted with buying

a yoghurt outside a nice-looking deli and thought it best not to tempt fate. Instead

I crossed the road and entered the park.

Everything looked so beautiful and I felt so shitty I could barely stay upright.

I followed a path and felt my age every step of the way. As the morning grew warmer

I found a nice grassy spot to lie on, and there I dozed for a pleasant few hours.

At some point I woke to raised, hectic voices. It was a pick-up game of football

and the goalpostsâtwo humped jerseysâwere only metres away. Twenty years ago I had

joined in these sorts of games at Holland Park. I remember one game played under

an early evening sky where the light actually seemed to stall and we had played on

and on in a state of suspended bliss. Skills I never knew I had revealed themselves;

a flashy slap of the ball off one foot then the other turned the goal-keep, a schoolteacher

with a long pre-war face, and I banged in the

shot past someone's shoe that was standing

in for one upright of the goalposts. A man on a bike who had stopped to watch actually

applauded. Funny that this man, so incidental and anonymous in every other respect,

should rise in my thoughts all these years later. I seem to recall telling someone

who had asked that I was from Sweden. I wanted origins more spectacular than my

own to go with that drive past the shoe upright. And afterwards, on this particular

night, the night of the goal by the young Swede, I went for a beer in the pub opposite

the park gatesâI've long forgotten its nameâand remember falling in with a Nigerian

officer on leave from the war in Biafra. He had a nasty gash over his forehead, and

two nicks in his cheek. Here was another occasion where I was all too aware that

I was speaking to a person of colour, a black man. At the same time I was also determined

to give the impression that his colour was neither here nor there. But of course

that was untrue. It was colour generally which had made an impression on me during

my first trip to London. That new colour white I'd not seen before, and now black.