Paris in the Twentieth Century (6 page)

Read Paris in the Twentieth Century Online

Authors: Jules Verne

Unnecessary

to add that she never derailed.

As for

their son, multiply his mother by his father, and you have Athanase Boutardin

for a coefficient, chief associate of the banking house Casmodage and Co., an

agreeable boy who took after his father for high spirits, and after his mother

for elegance. It was impossible to pass a witty remark in his presence; it

seemed to miss him altogether, and his brows frowned over his vacant eyes. He

had won the first banking prize in the grand competition. It might be said that

he not only made money work but wore it out; he smelled of usury; he was

planning to marry some dreadful creature whose dowry would energetically make

up for her ugliness. At twenty, he already wore aluminum- framed spectacles.

His narrow and deep-rutted mind impelled him to tease his clerks by touches of

the whip. One of his tricks consisted of claiming his cashbox was empty,

whereas it was stuffed with gold and notes. He was a wretched creature, without

youth, without heart, without friends. Greatly admired by his father.

Such was

this family, this domestic trinity from which young Dufrénoy was seeking aid

and protection. Monsieur Dufrénoy, Madame Boutardin's brother, had possessed

all the sentimental delicacy and the sensitivity which in his sister were

translated as asperities. This poor artist, a highly talented musician, born

for a better age, succumbed in youth to his labors, bequeathing his son no more

than his poetical tendencies, his aptitudes, and his aspirations.

Michel

knew he had an uncle somewhere, a certain Huguenin, whose name was never

mentioned, one of those learned, modest, poor, resigned creatures who are the

shame of opulent families. But Michel was forbidden to see him, and he had

never even encountered him; hence there was no hope in that direction.

The

orphan's situation in the world was, therefore, nicely determined: on the one

hand, an uncle incapable of coming to his aid, on the other, a family rich in

those qualities which are readily coined, with just enough heart to send the

blood through its arteries.

There

was not much here for which to thank Providence.

The next

day, Michel went downstairs to his uncle's office, a somber chamber if ever

there was one, and papered with a serious material: here were gathered the

banker, his wife, and his son. The occasion threatened to be a solemn one.

Monsieur

Boutardin, standing on the hearth, one hand in his vest and puffing out his

chest, expressed himself in the following terms:

"Monsieur,

you are about to hear certain words which I must ask you to engrave upon your

memory. Your father was an artist—a word which says it all. I should like to

think that you have not inherited his unfortunate instincts. Yet I have

discerned in you certain seeds which must be rooted out. You tend to flounder

in the sands of the ideal, and hitherto the clearest result of your efforts has

been this prize for Latin verses, which you so shamefully brought here

yesterday. Let us reckon up the situation. You are without fortune, which is a

blunder. Moreover, you have no parents. Now, I want no poets in my family, you

must realize. I want none of those individuals who spit their rhymes in

people's faces; you have a wealthy family—do not compromise us. Now, the

artist is not far from the grimacing humbug to whom I toss a hundred sous from

my box for him to entertain my digestion. You understand me. No talent.

Capacities. Since I have observed no particular aptitude in you, I have decided

that you must enter the Casmodage and Co. banking house, under the direction of

your cousin; take him as your example. Work to become a practical man! Remember

that a certain share of the blood of the Boutardins flows in your veins, and

the better to recall my words, take heed never to forget them. "

In 1960,

as may be seen, the race of Prudhomme

[7]

was not yet extinct; the finest traditions had been preserved. What could

Michel reply to such a diatribe? Nothing, hence he was silent, while his aunt

and his cousin nodded their approval.

"Your

vacation, " the banker resumed, "begins this morning, and ends this

evening. Tomorrow you shall be introduced to the head of Casmodage and Co. You

may go. "

The

young man left his uncle's office, eyes filled with tears; yet he braced

himself against despair. "I have no more than a single day of freedom,

" he mused, "at least I shall spend it as I please; I have a little

money, and

it

I shall spend on books beginning with the

great poets and illustrious authors of the last century. Each evening they will

console me for the vexations of each day. "

Concerning

Some Nineteenth-Century Authors, and the Difficulty of Obtaining Them

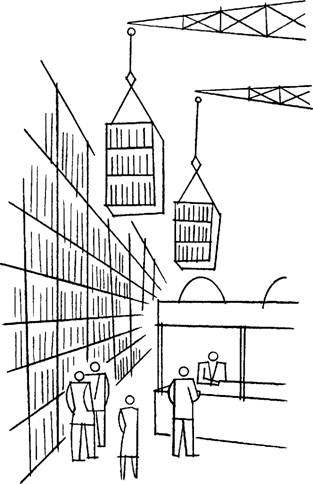

Michel

hurried out into the street and made for the Five Quarters Bookstore, an

enormous warehouse on the Rue de la Paix, run by an important State official.

"All the productions of the human mind must be here, " the young man

reflected, as he entered a huge vestibule, in the center of which a telegraph

bureau kept in touch with the remotest branch stores. A legion of employees kept

rushing past, and counterweighted lifts, set into the walls, were raising the

clerks to the upper shelves of the various rooms; there was a considerable

crowd in front of the telegraph desk, and porters were struggling under their

loads of books.

Amazed,

Michel vainly attempted to estimate the number of books that covered the walls

from floor to ceiling, their rows vanishing among the endless galleries of

this imperial establishment. "I'll never manage to read all this, "

he thought, taking his place in line; at last he reached the window.

"What

is it you want, sir?" he was asked by the clerk in charge of requests.

"I'd

like the complete works of Victor Hugo, " Michel replied.

The

clerk's eyes widened. "Victor Hugo? What's he written?"

"He's

one of the great poets of the nineteenth century, actually the greatest,

" the young man answered, blushing as he spoke.

"Do

you know anything about this?" the man at the desk asked a second clerk in

charge of research.

"Never

heard of him, " came the answer. "You're sure that's the name?"

"Absolutely

sure. "

"The

thing is, " the clerk continued, "we rarely sell literary works here.

But if you're sure of the name... Rhugo, Rhugo... " he murmured, tapping

out the name.

"Hugo,

" Michel repeated. "And while you're at it, please ask for Balzac,

Musset, Lamartine...

"Scholars?"

"No!

They're authors. "

"Living?"

"They've

been dead for over a century. "

"Sir,

we'll do all we can to help you, but I'm afraid our efforts will require some

time, and even then I'm not sure..."

"I'll

wait, " Michel replied. And he stepped out of line into a corner, abashed.

So all that fame had lasted less than a hundred years!

Les Orientales, Les M

é

ditations, La Com

é

die Humaine—

forgotten,

lost, unknown! Yet here were huge crates of books which giant steam cranes were

unloading in the courtyards, and buyers were crowding around the purchase desk.

But one of them was asking for

Stress Theory

in

twenty volumes, another for an

Abstract of Electric Problems,

this one for

A

Practical Treatise for the Lubrication of Driveshafts,

and that one for the latest

Monograph on Cancer of the Brain.

"How

strange!" mused Michel. "All of science and industry here, just as at

school, and nothing for art! I must sound like a madman, asking for literary

works here—am I insane?" Michel lost himself in such reflections for a

good hour; the searches continued, the telegraph operated uninterruptedly, and

the names of "his" authors were confirmed; cellars and attics were

ransacked, but in vain. He would have to give up.

"Monsieur,

" a clerk in charge of the Response Desk informed him, "we don't have

any of this. No doubt these authors were obscure in their own period, and their

works haven't been reprinted... "

"There

must have been at least half a million copies of

Notre-Dame de Paris

published in Hugo's lifetime, " Michel replied.

"I

believe you, sir, but the only old author reprinted nowadays is Paul de Kock

[8]

,

a moralist of the last century; it seems to be very nicely written, and if

you'd like—"

"I'll

look elsewhere, " Michel answered.

"Oh,

you can comb the entire city. What you can't find here won't turn up anywhere

else, I can promise you that!"

"We'll

see, " Michel said as he walked away.

"But,

sir, " the clerk persisted, worthy in his zeal of being a wine salesman,

"might you be interested in any works of contemporary literature? We have

some items here that have enjoyed a certain success in recent years—they

haven't sold badly for poetry..."

"Ah!"

said Michel, tempted, "you have modern poems?"

"Of

course. For instance, Martillac's

Electric Harmonies,

which

won a prize last year from the Academy of Sciences, and Monsieur de Pulfasse's

Meditations on Oxygen;

and we have the

Poetic Parallelogram,

and even the

Decarbonated Odes..."

Michel

couldn't bear hearing another word and found himself outside again, stupefied

and overcome.

Not

even this tiny amount of art had escaped the pernicious influence of the age!

Science, Chemistry, Mechanics had invaded the realm of poetry! "And such

things are read, " he murmured as he hurried through the streets,

"perhaps even bought! And signed by the authors and placed on the shelves

marked

Literature.

But

not one copy of Balzac, not one work by Victor Hugo! Where can I find such

things—where, if not the Library..."

Almost

running now, Michel made his way to the Imperial Library; its buildings,

amazingly enlarged, now extended along a great part of the Rue de Richelieu

from the Rue Neuve-des-Petits-Champs to the Rue de la Bourse. The books,

constantly accumulating, had burst through the walls of the old Hotel de

Nevers. Each year fabulous quantities of scientific works were printed; there

were not suppliers enough for the demand, and the State itself had turned

publisher: the nine hundred volumes bequeathed by Charles V, multiplied a

thousand times, would not have equaled the number now registered in the

library; the eight hundred thousand volumes possessed in 1860 now reached over

two million.

Michel

asked for the section of the buildings reserved for literature and followed the

stairway through Hieroglyphics, which some workmen were restoring with shovels

and pickaxes. Having reached the Hall of Letters, Michel found it deserted, and

stranger today in its abandonment than when it had formerly been filled with

studious throngs. A few foreigners still visited the place as if it were the

Sahara, and were shown where an Arab died in 1875, at the same table he had

occupied all his life.

The

formalities necessary to obtain a work were quite complicated; the borrower's

form had to contain the book's title, format, publication date, edition number,

and the author's name—in other words, unless one was already informed, one

could not become so. At the bottom, spaces were left to indicate the borrower's

age, address, profession, and purpose of research.