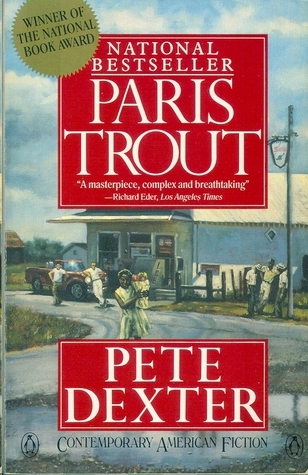

Paris Trout

Paris Trout

Pete

Dexter

1988

This book is for

James

Maurice Quinlan

And Mickey Rosati

two

of a kind.

I

ROSIE

Part One

IN THE SPRING of that year an epidemic of rabies

broke out in Ether County, Georgia. The disease was carried

principally by foxes and was reported first by farmers, who, in the

months of April and May, shot more than seventy of the animals and

turned them in to the county health officer in Cotton Point.

The heads were removed, wrapped in plastic, and sent

to the state health department in Atlanta, where eleven were found to

be rabid. There is no record of human beings contracting the disease

— the victims for the most part were cattle — although two

residents of an outlying area of Cotton Point called Damp Bottoms

were reportedly bitten.

One of them, an old man known only as Woodrow, was

found lying under his house a day later, dead. He was buried by the

city in a bare, sun-baked corner of Horn Cemetery without medical

tests and without a funeral.

The other was a fourteen-year-old girl named Rosie

Sayers, who was bothered by nightmares.

Rosie Sayers was tall and delicately boned, and her

front teeth lay cross her lips like sleeping white babies. She was

afraid of things she could not see and would not leave the house

unless she was forced.

The house was flat-roofed and warped. It had five

rooms, and the wallboards that defined them were uneven, so you could

see through the walls from any of the rooms into the next.

She lived in this house with her mother and her

brothers and sisters. There were fourteen of them in all, but Rosie

had never counted the number. She had never thought to.

The brothers and sisters slept through Rosie's

screams in the night — it was a part of things, like the whistling

in her youngest brother's breathing — but her mother's visitors,

unaccustomed to the girl's affliction, would sometimes bolt up in bed

at the noise, and sometimes they would stumble into their pants in

the dark and leave.

Her mother called the dreams "spells" and

from time to time stuck needles in the child's back as an exorcism.

Usually after one of her visitors had left in the night. Rosie would

stand in front of her, bare-backed, allowing it.

On the day she was bitten by the fox, Rosie Sayers

had been sent into town to buy a box of .22 caliber shells from Mr.

Trout. Her mother had a visitor that week who was a sportsman.

Mr. Trout kept a store on North Main Street. There

was a string on the door that tripped a bell when anyone walked in.

Colored people stopped just inside the door and waited for him. White

people picked out what they wanted for themselves. There was one

light inside, a bare bulb, hanging from a cord in the back. He came

out of the dark, it reminded her of a ghost. He glowed tall and

white. "What is it?" he said.

"

Bullets," she said. The word lost itself

in the darkness, the sound of the bell was still in the room.

"

Speak up, girl."

"Twenty-two bullets," she said.

He turned and ran a long white finger along the shelf

behind, and when he came back to her, he was holding a small box.

"That's seventy cent," he said, and she reached into the

tuck of her shirt and found the dollar her mother had given her. It

was balled-up and damp, and she smoothed it out before she handed it

over.

He took the money and made change from his own

pocket. Mr. Trout didn't use a cash register. He put the box of

shells in her hand, he didn't use bags much either. She had never

held a box of shells before and was surprised at the weight. He

crossed his arms and waited.

"

I ain't got forever," he said.

* * *

SHE WALKED to the north end of town and then followed

the Georgia Pacific Railroad tracks, east and north, back to the

sawmill. Damp Bottom sat behind the mill, built on rose-colored dirt,

not a tree to be seen. It made sense to her that trees wouldn't dare

to grow near a sawmill.

There was a storage shed between the mill and the

houses, padlocked in front and back, with small, dirty windows on the

side. Her brothers said there were dead men inside, but she never

looked for herself. Rosie's grandmother had died in bed, her mouth

open and contorted, as if that were the route her life took leaving

her, and that was all the dead people she ever meant to see.

She passed the windows wide, averting her eyes, and

when she was safely by and looked in front of herself again, she saw

the fox. He was dull red and tired and seemed in some way to

recognize her.

She stopped cold in her tracks, the fox picked up his

head. She took a slow step backwards, and he followed her, keeping

the same distance. Then he moved again, closer, and seemed to sway.

She heard her own breathing as she backed away.

The movement only seemed to draw him; something drew

him. "Please, Mr. Fox," she said, "don't poison me. I

be out of your way, quick as you seen me, I be gone."

She knew foxes had turned poisonous from her

brothers. Worse an a snake. She stopped again, and he stopped with

her. Her brothers 'd when the poison fox bit you, you were poison

too.

The fox cocked his head, and she began to run. She

didn't know where. Her legs were strong; but before she had gone ten

steps, they seemed to tangle in each other, and she was surprised,

looking down just before she fell, to see the fox between them. Then

she closed her eyes and hit the ground.

She never felt the bites. The fox growled — the

sound was higher-pitched than a dog, and busier — and then she

kicked out with her heels and felt his coat and the bones beneath it.

He cried out, and when she kicked again nothing was there.

She opened her eyes, and as fast as he had come he

was gone. She stood up slowly, collecting her breath, and dusted

herself off. She was thorough about it, she didn't like to be dirty,

and it was only when her hand touched the inside of her calf and felt

blood that she knew that he had opened her up.

She saw the bites then, two small openings on the

same leg, closer to her ankle than her knee. The blood wasn't much

and had already dried everywhere except near the tears in the skin.

She sat back down on the ground and began to cry. The clay was

scorched, but she didn't feel that either.

She cried because she was poisoned.

In a few minutes the crying began to hurt her head,

and she stood up again, shaky-legged now, afraid her mother would

know what had happened. Afraid of what her mother would do.

She spit in the palm of her hand and wiped at the

blood on her leg, over and over, until her mouth was too dry to spit.

Then she rubbed both her hands on the ground, picking up

orange-colored dust, and covered her legs and her knees, not to draw

attention to the one that was injured.

She put dust on her elbows and some on her cheeks and

neck. Her mother would be angry, to have her walk into the house

dirty when she had a visitor, but she wouldn't know about the fox.

She remembered the visitor.

She turned a circle, looking for the box of shells.

It was a present for him because he was a sportsman. Her mother said

he might shoot them rabbits for supper.

The box was gone. She looked all around her and then

back toward the shed. She traced her steps past the shed to the spot

she had been when she looked up and saw the fox. She searched the

ground and the weeds growing around the shed, looking up every few

seconds because she was afraid the fox would be there again.

The fox was gone, though, and so were the bullets.

She stood still and waited, she didn't know for what.

The sun moved in the sky. She stopped crying; the scared feeling

passed and left her calm. She wondered if her mother would allow the

visitor to whip her.

She had done that before.

Her thoughts turned again

to the bullets and then from the bullets to the place she had gotten

them. Mr. Trout wasn't as frightening now; it felt like he might be

glad to see her again. And when she finally moved away, feeling a

tightness at first in the leg where the fox had bitten her, it was

back in the direction of the store.

* * *

ROSIE SAYERS could not tell time, and her sense of it

was that it belonged to some people and not to others. All the white

people had it, and all the colored people who owned cars. Her

mother's visitors had it, they would mention it when they left.

"Lordy, look at the time .... "

She worried now that the time had run out for the

stores to be open. She hurried her walk, following the railroad

tracks. The tracks curved and then fed themselves into a bridge on

the edge of town. A train was stopped there, car after car of lumber

as far as she could see. The smell of fresh-cut pine.

She climbed the embankment to the bridge, using her

hands, and when she came to the top the whistle blew, and the cars

banged against each other as the slack in their couplings was pulled

from the front, and then, together, they began to move slowly up the

track.

And she watched the train from the top of the hill,

standing on the bridge that led to town, and she thought of jumping,

down into the dark places between the cars, and being taken in that

way to the end of the tracks. And for a moment there seemed to be

another person inside her too, someone who wanted to jump.

She remembered time then,

and the stores and walked away from the train and back into town. She

wondered if other people had another person inside them too.

* * *

SHE THOUGHT she was too late. The stores on the lower

part of Main Street were half dark inside, and still. White people

had gone home. She thought of her mother again and hurried. It felt

like her mother was watching.

Mr. Trout's store was as dark as the others, but it

had been dark earlier too. She tried the door. The handle turned, she

pushed it open. She heard the bell ring and stepped inside and

waited. The air was heavy and hard to breathe. She felt herself

suspended in it, with the smell of everything there for sale.

There was a fussing in the back, someone was angry.

She reached for the door, afraid now that it had somehow locked and

that she was trapped inside. Then there was a voice, closer.

"

May I help you, miss?"

Rosie turned and saw a lady, as ghostlike as Mr.

Trout himself but pretty. The lady straightened and wiped at her eyes

with the back of her hand, getting herself right.

Rosie had never seen a white person cry before —

none except the little ones — and it surprised her that they had

those feelings too, and that the lady would allow herself to be seen

in that condition.

'

°What is it, child?" the lady said. She had a

sweet voice, as if in the darkness of the store she couldn't see who

it was she was talking to.

"Twenty-two bullets," she said.

The lady turned and looked on the shelves behind her.

The girl knew where Mr. Trout found the bullets before, but she was

reluctant to speak. The lady's finger moved along the goods stacked

into the shelves and passed right over them.

"That's them," Rosie said, and the lady

jumped at the sound of the voice behind her and something fell off

the shelf. The child backed away from the counter, covering her

mouth. The lady turned around, though, and smiled. "I'm afraid

I'm not used to finding bullets," she said.

"

No, ma'am, me neither."

And it was like they were in the same mess, and for a

moment it was like the fox had never bitten her.

The lady knelt to pick up the things on the floor.

Rosie would have helped; but there was a counter between them, and

she knew without being told to stay on her own side. Even if they

were in the same mess, white people would think she was stealing.

The lady came back up slowly, flushed and serious.

Rosie heard her bones pop. "Now," she said, "where

were we?"

"I ain't moved," Rosie said, and showed the

lady her hands.

The lady did not look at her hands. She smiled, so

small it might have been something that hurt. "That's an

expression," she said. "It means, What were we doing?"