Pericles of Athens (13 page)

Read Pericles of Athens Online

Authors: Janet Lloyd and Paul Cartledge Vincent Azoulay

After the peace had been signed, the Delian League no longer had as much

raison d’être

, and that is perhaps why the levying of tribute was suspended in 448 B.C.

2

However, that respite was short-lived, and the Athenians then continued to receive

a

phoros

even though the Persian threat had disappeared. These taxes were resented all the

more because in the late 450s the league’s treasury had been transferred to Athens.

The sum to be paid as tribute was fixed every four years by the Athenian

ekklēsia

, which summoned all the allies at the time of the great Panathenaea, in order to

reveal to them the sum that they were to pay annually. All of this is attested by

Cleinias’s decree.

3

It was therefore certainly not by chance that several major revolts broke out within

this league that now had no purpose. In 447/6 Euboea revolted against Athens, which,

after putting down the uprising, imposed democratic systems on the island and installed

cleruchies, garrisons of Athenian soldiers, who settled there.

4

It was at this point that the city of Histiaea became the cleruchy of Oreos. In 440/39,

the island of Samos was pacified after a long siege, as was then the city of Byzantium.

The vocabulary used to speak of the league and its members now changed: the Athenians

spoke no longer of their

hēgemonia

but of their

arkhē

—their domination—and they now referred to the league members as

hupēkooi

, dependents, not allies.

5

During the Peloponnesian War, the revolts multiplied, prompting the Athenians to

exact heavy reprisals. In 427, Mytilene was forced back into the league and the island

of Lesbos was subjected to heavy repression. In 425, tribute was almost tripled in

order to cope with the heavy expenses of warfare. Athenian imperialism had now reached

its peak. It was not until the disastrous result of the Sicilian expedition (415–413

B.C.) and, above all, the last years of the war that Athens’s grip loosened; the league

was finally dissolved at the end of the conflict, in 404 B.C.

Did Pericles play a role in the imperial metamorphosis of the Delian League? Did he,

as leader of the people, act as a catalyst in the aggressive tendencies of the Athenians

or did he, on the contrary, try to keep them in check? In order to resolve that alternative,

we must first determine a crucial question: exactly when was the league transformed

into an empire (

figure 2

)?

The Slide into Imperialism: A Periclean Turning Point?

Precisely when did Athens increase its power over the members of the Delian League

to the point of turning them into mere subjects, or even “slaves”? Among historians,

this tricky question eludes a consensus. Specialists on

the Athenian Empire disagree on the dating of the complex epigraphical evidence. A

number of decrees testifying to the growing imperialism of Athens have been found,

but it has not been possible to date them precisely, on account of their lamentable

state of preservation. While most epigraphists place the date of their engraving between

450 and 440, some specialists defend a later dating, around 430/420.

6

One might remain unmoved by this erudite battle were it not for the fact that what

is at stake here is crucial for an understanding of the nature of the Periclean empire

and the role that Pericles himself played in its development. There are two possibilities:

if these inscriptions go back to the mid-fifth century, the hardening of Athenian

imperialism must have taken place under Pericles and probably at his instigation;

if, on the contrary, they were not engraved until the time of the Peloponnesian War,

“only the war forced the Athenians to tighten their grip on the Aegean world,”

7

so Pericles, who died at the beginning of the conflict, was in no way implicated

in the process.

8

To be quite frank, the second alternative does not seem credible. Whatever the date

of the decrees in question, there is plenty of other evidence of the Athenian descent

into imperialism as early as the middle of the fifth century. On this basis, it might

seem logical to detect signs of specifically Periclean policies, particularly since

some authors who were contemporaries of the

stratēgos

make this their justification for taking a hard line in this matter. One such is

Stesimbrotus of Thasos, a native of an island placed under Athenian control, who certainly

criticizes Pericles for his cruel behavior toward the people of Thasos and contrasts

this to the supposed moderation of Cimon.

9

In reality, that contrast does not withstand scrutiny. What strikes one upon reading

the sources that are available is above all how quickly the Delian League was transformed

into an empire placed at the service of Athens. In fact, this happened as early as

the time when Cimon dominated the political life of the city. So it was probably under

his leadership that the first of the allies’ revolts was repressed. As early as 475,

the city of Carystus, in Euboea, was forced, against its will, to join the league.

In 470 or 468, Naxos revolted, and, as Thucydides declares, “this was the first allied

city to be enslaved [

edoulōthē

] in violation of the established rule” (1.98.4). However, the first rebellion of

any magnitude was that of Thasos, between 465 and 463. It took the Athenians two years

to overcome this city that possessed, on the continent, mineral resources and forests

that were eminently desirable.

10

When the conflict was over, the city precinct was razed to the ground and its navy

was confiscated. The people of Thasos became tribute-payers to Athens and lost their

liberty. Very soon, the Athenians also insisted that the cities that had revolted,

once they rejoined the alliance, should solemnly swear

never again to secede, as we know from an inscription in Erythrae, a city in Asia

Minor that rejoined the league some time between 465 and 450 B.C.

11

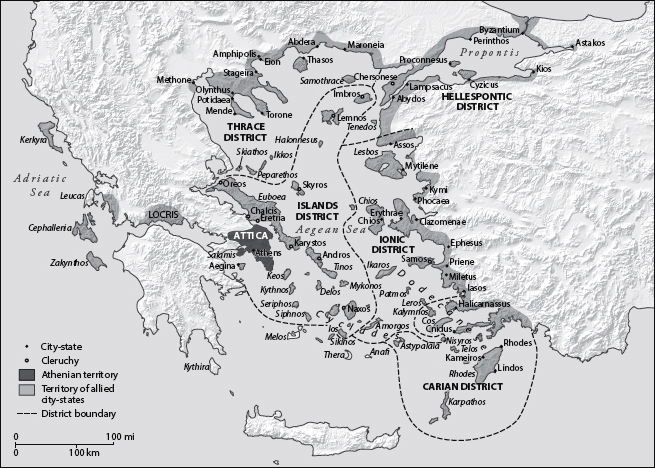

FIGURE 2.

Map of the Athenian Empire ca. 431 B.C.

An aggressive imperialist thrust was thus initiated as early as the second third of

the fifth century. No Athenian leader could afford to resist it if he wished for the

support of the people. In this context, Cimon repressed the revolts of the allies

as regularly as did Pericles after him. It was Cimon who was in charge of the lengthy

siege of Thasos in 465–463 and also he who decisively promoted the development of

cleruchies, the Athenian garrisons that were installed in allied territories.

12

Apart from a few minor disagreements, the political leaders clearly shared in common

the conviction that the empire constituted the guarantee of Athenian sociopolitical

stability. There may have been disagreement about the methods to be adopted, but there

was none where the principle was concerned: the empire was vital for Athens, so, if

necessary, the allies had to be repressed by force. Moreover, the transfer of the

Delian League’s treasury, often interpreted as the ultimate symbol of the hardening

attitude of imperialism, may quite possibly have taken place before 454—the date when

it is actually mentioned—indeed, it may have been carried out even prior to the victory

of Eurymedon, at the beginning of the 460s.

13

All the same, it would be exaggerated to detect no change at all in Athenian politics

during the years between 440 and 430. However, such developments probably owed nothing

to Pericles himself but everything to the transformation of the geopolitical context

and, in particular, the establishment of peace, de facto if not

de iure

, with Persia. With the signing of the peace of Callias in 449, Athenian domination

in effect became radically illegitimate in the eyes of the allies/subjects: the league

was now subject to a whole spate of revolts, which were countered by increasing repression.

Faced with mounting challenges, Pericles unhesitatingly resorted to force and was,

as a result, sometimes accused of cruelty. This practical experience of his, marked

by a series of bloody incidents, now led him, at the theoretical level, to develop

his lucid thinking about the empire and the need to maintain it.

P

ERICLES

F

ACED BY THE

A

LLIES

: I

MPERIAL

P

RACTICES AND

R

EPRESENTATIONS

The Recourse to Force: Periclean Cruelty

Still today, certain historians seek to palliate the image of Pericles’ actions in

the face of the allies. Donald Kagan, in his biography, emphasizes the relative moderation

of the

stratēgos

’s behavior in this episode.

14

“Save Private Pericles!”: the

stratēgos

cannot possibly have been cruel and risk besmirching

the Greek miracle with an indelible stain! That is an eminently ideological attitude

and it should be analyzed in relation to the biographer’s own political background.

In this respect, his political trajectory is instructive: having started out as a

liberal—in the American sense of the term—Kagan became a Republican in the 1970s and

then, in the 1990s, was one of the founders of a neo-conservative “think tank” (“Project

for the New American Century”). Meanwhile, one of his sons became John McCain’s advisor

on foreign policy. So it is perfectly logical that, as an apostle of American interventionism

abroad, Kagan should present us with a Pericles who is both firm yet temperate and

is the epitome of moderation when faced with undisciplined and recalcitrant allies.

15

However, that supposed moderation is a fiction. During the years in which he played

a leading role, Pericles made sure that the allies’ revolts were shamelessly repressed,

sometimes even with cruelty. In truth, the

stratēgos

was intimately associated with the repressive policies of Athens. Significantly enough,

Thucydides, who only mentions Pericles three times in his long account of the

pentēkontaetia

(the period of almost fifty years [478–431] that separated the end of the Persian

Wars from the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War) twice mentions his direct involvement

in forcing the allies to toe the line.

The Euboean Revolt

First, the historian describes his participation in the punishment of Euboea, in 446

B.C.: “The Athenians again crossed over into Euboea under the command of Pericles

and subdued the whole of it; the rest of the island they settled by agreement, but

expelled the Histiaeans from their homes and themselves occupied their territory.”

16

That was how Pericles wreaked his revenge on those who, having captured an Athenian

vessel, massacred the entire crew.

17

The city was turned into a cleruchy and the rest of the Euboean cities were placed

under strict supervision, as is attested epigraphically by two decrees concerning

Eretria and Chalcis.

18

The comic poets dwelt upon this bloody episode—in particular, in Aristophanes’

Clouds

, a play that was staged for the first time in 423 B.C. Referring to Euboea, the poet

has one of the characters say: “We have stretched it enough, we and Pericles!”

19

The treatment meted out to the rebels was so traumatic that it was still haunting

the Athenian conscience nearly forty years later. When the Peloponnesian War ended,

at the news of the defeat at Aigos Potamoi, in 405, the Athenians were gripped by

terror, fearing now to see the allies, so long tyrannized, seeking revenge for the

exactions that they had suffered. And in the long list of outrages, the crushing of

the Euboean

revolt figured prominently: “That night, no one slept, all mourning, not for the lost

alone, but far more for their own selves, thinking that they would suffer such treatment

as they had visited upon the Melians, colonists of the Lacedaemonians, after reducing

them by siege, and upon the Histiaeans and Scionaeans and Toronaeans and Aeginetans

and many other Greek peoples” (Xenophon,

Hellenica

, 2.2.3). The repression of Euboea in 446, led by Pericles, thus symbolized all the

harshness of Athenian imperialism, to the point of leaving an indelible mark on the

civic conscience.

The Samos Affair

Pericles’ second intervention left just as deep a scar. In 440–439 B.C.,

20

taking advantage of an altercation between Samos and Miletus over the possession

of Priene, in Asia Minor, the Athenians embarked on a long war against the Samians,

who had defected and left the Delian League. We need not dwell on the ins-and-outs

of the conflict but should note that this war turned out to be extremely costly for

Athens, both in men and in money. In money, first: an inscription records the total

sum of the expenses for the war. The final sum was as high as 1,400 talents, more

than three years’ accumulated tribute, which was later paid back solely by the Samians!

21

But the war was also costly in men and was marked by an extreme violence that struck

the imagination of ancient authors. Two stories focus on the cruelty of the conflict;

it was a violence that was initially reciprocal but for which, later on, the Athenians

alone were held responsible.