Pericles of Athens (15 page)

Read Pericles of Athens Online

Authors: Janet Lloyd and Paul Cartledge Vincent Azoulay

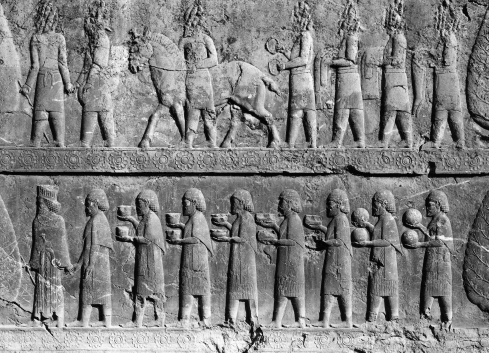

This strange mimicry had two symmetrical functions. It was intended, within the urban

setting of the city itself, to commemorate the Athenian victory in the Persian Wars.

Better still, by creating this hall for spectacles, the Athenians were manipulating

the despotic symbolism associated with Xerxes’ tent and adapting it to democratic

purposes. Whereas the original pavilion had, in principle, been reserved for the exclusive

enjoyment of the Great King, the Odeon was conceived as an edifice open to all, constructed

for the pleasure of the entire population. However, this architectural choice probably

conveyed a quite different message to the foreigners who passed through Athens. The

edifice must have struck them as a veritable imperialist manifesto.

38

The Odeon, which imitated the splendors of Achaemenid architecture, returned the

allies to the status of subjects and reminded them that they had, in truth, simply

swapped masters. We should furthermore bear in mind that it was on the staircase leading

to the Apadana, the throne-room in Persepolis, on which the Odeon drew freely for

inspiration, that the long cohorts of tributary peoples had been represented, bringing

their contributions to the Great King, in a lengthy procession (

figure 5

). Nor was that association

solely metaphorical: in Athens, the allies of the Delian League were obliged to pass

in front of Pericles’ Odeon when they came to deposit their tribute in the theater

of Dionysus.

39

This edifice brilliantly symbolized their new status as tribute-bearers, strictly

in line with the imperial Achaemenid heritage.

40

FIGURE 5.

Tribute-bearers (maybe Ionians) from the ceremonial staircase (northern stairway)

of the Apadana (Iran: Persepolis, end of the sixth century B.C.). In

Persepolis and Ancient Iran

with an introduction by Ursula Schneider, Oriental Institute. © 1976 by The University

of Chicago. Image courtesy of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

The same reasoning may be applied to the city’s most famous monument, the Parthenon,

for in many respects this too testified to the hardening of Athenian imperialism.

The Parthenon: A Marble Symbol of Athenian Imperialism

There can be little doubt that the great building program launched in Athens after

450 was associated with imperial dynamics. Pericles’ opponents would even reproach

him for having misapplied imperial revenues in order to realize his monumental policy

and, especially, to build the Parthenon with its statue of Athena Parthenos: “Hellas

is insulted with a dire insult and manifestly subjected to tyranny when she sees that,

with her own enforced contributions for the war, we are gilding and bedizening our

city, which, for all the world like a wanton woman, adds to her wardrobe precious

stones and costly statues and temples worth their millions” (Plutarch,

Pericles

, 12.2). To be sure, this declaration calls for a measure of qualification. For it

is by no means certain that the Parthenon was built with the money obtained from the

allies.

41

All the same, the fact remains that, in the imaginary representations of the Athenians

and of their allies, this building remained closely associated with the onward march

of the empire, for was it not used to shelter the league’s treasury, which was transferred

to Athens in 454 B.C., at the latest?

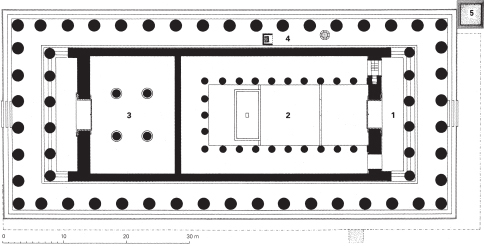

It is, moreover, this practical necessity—namely, to find a place for the treasury—that

explains the strange layout of the monument. The fact is that, ordinarily, a Greek

temple was built in accordance with a stereotyped schema: a vestibule (

pronaos

), then a central hall containing the cult statue (

naos

), and, finally, a back room (

opisthodomos

), for the use of the temple staff. In comparison to this canonical arrangement, the

structure of the Parthenon is, to say the least, unusual—and for two reasons: in the

first place, the huge dimensions of the

naos

contrast strongly with the limited area taken up by the

pronaos

and the

opisthodomos

(

figure 6

). The fact was that the central hall had to be spacious enough to house the immense

statue of Athena Parthenos. Then, an extra room, with four columns, was set between

the

naos

and the

opisthodomos

: a hall that gave its name to the edifice as a whole, the Parthenon, “the room for

the virgin.”

42

It was in this space that the city treasures were stored, in particular the treasury

of the Delian League. This extra room that housed the allies’ tribute was thus the

very symbol of Athenian imperialism. It is surely not merely by chance that the four

columns that supported the roofing of this room were in the Ionic style. Incorporating

this Ionic style at the very heart of a Doric edifice was a way for the Athenians

to give material expression to their domination over a league made up chiefly of Ionian

cities.

FIGURE 6.

Athens, Acropolis, the Parthenon (ca. 447–437 B.C.): plan of the temple. Drawing

by M. Korres. Courtesy of the Media Center for Art History at Columbia University.

Far from being a temple,

43

the Parthenon was a treasury and a monument that glorified imperialism and symbolized

the hardening or even petrification of Athenian domination. In this respect, the chronology

is significant: the construction of the Parthenon began in 447, one year before the

great Euboean revolt, and it was completed in 438, one year after the Samos affair.

In truth, there is nothing specifically Periclean about the management of the empire,

except a particular way of theorizing about its necessity, and its presentation. Although

we should perhaps not impute to Pericles in particular the responsibility for the

city’s slide into imperialism, Pericles certainly did take over this new order without

compunction, both in practice and in the representations that he promoted. Now we

must evaluate to what degree the imperial dynamic and democratization of the city

went hand in hand. Let us do so by analyzing the bases of the Periclean economy.

CHAPTER 5

A Periclean Economy?

T

oday, an “economy” means the production, distribution, and consumption of goods, both

material and immaterial. But this term, which was forged in Athens in the classical

period, had a sense that was very different from its contemporary one. In the fourth

century,

oikonomia

defined, first, the way of managing an

oikos

, an agricultural property. It was only by extension that the term came to designate

the management of the resources of a city, or even an empire. This mismatch between

oikonomia

and “economy,” the ancient formulation and the modern definition, for a long time

led historians to doubt the existence, in the Greek world, of any economic sphere

separate from all other social activities.

One group of ancient historians thus maintains that the cities knew of nothing more

than a primitive form of economy, characterized by the preponderant part played by

agriculture, the role of self-subsistence, the limited place of crafts and money,

and an absence of major exchange systems. That view has long since been challenged

by experts who, on the contrary, emphasize the dynamism of the ancient economy. In

this battle between “primitivists” and “modernists” that started at the end of the

nineteenth century, the Athens of Pericles constitutes a particularly animated scene

of disagreement.

The fact is that, in the course of the fifth century, the democratic city experienced

a phase of extraordinary prosperity. Its silver coinage was developing so rapidly

that the little Athenian “owls” became the common currency of a large part of the

Greek world. Its port, Piraeus, became the major seat of exchange for the eastern

Mediterranean. However, historians are not in agreement as to the nature of the economic

prosperity of Athens: did it result from an internal dynamic, in particular a rational

management of resources both private and public, or was it no more than a by-product

of Athens’s exploitation of the Delian League? What were the bases of the Athenian

economy under Pericles? Was this an economy based on the revenues that Athens obtained

from the hegemonic position that it acquired, or did its vitality spring from the

rise of new economic ways of proceeding within the city? And, in any case, is it really

possible to assign to Pericles a specific role in any such evolution?

To find answers to these questions, we must begin by focusing upon the private sphere:

can we detect the existence of any Periclean

oikonomia

—that is to say, any specific way of managing an

oikos

and one’s own personal assets? According to the ancient authors, the

stratēgos

administered his own patrimony extremely carefully, radically rejecting extravagant

behavior and the kind of practices that led one into debt and that were then favored

by the Athenian elite.

When we pass from the private sector to the civic level, the questions change. They

now concentrate on the part that the empire played in the economic dynamism of Athens.

Even if it is clear that the Athenians drew substantial benefits, both direct and

indirect, from the empire, this does not mean that their prosperity stemmed solely

from the tribute that they levied on their subject cities. Today, most historians

think that the policy of “major constructions” associated with the name of Pericles

was financed only partly by the league treasury, which was transferred to Athens before

454.

Whatever the exact degree of the economic exploitation of the allies, the city also

profited from other large revenues—what the Greeks called

prosodoi

. The Athenians took to using these sums of money in a new way: they redistributed

part of them to the community in the form of wages and civic allowances. Perhaps this

was the true specificity of the Periclean economy: a new way of redistributing wealth

to beneficiaries who, in return, became more strictly controlled. In this major development,

Pericles certainly played a decisive role.

P

ERICLES AND A

R

ATIONAL

M

ANAGEMENT OF THE

O

IKOS

: T

HE

B

IRTH OF A

“M

ARKET

E

CONOMY

”

The

Oikonomia Attikē

Etymologically,

oikonomia

designates the controlled management (

nomos

comes from

nemein

, with the root meaning “distribute” and so “manage”) of a household. Far from identifying

with the modern notion of an economy, initially it concerned only the private sphere

and, above all, affected only agricultural activity, to the detriment of other forms

of production and distribution, such as artisan activity and commerce.

It is true that agriculture constituted the essential part of the wealth that was

produced in the Greek world—as much as 80 percent of its total value.

1

This predominance of agricultural activity has sometimes led historians to represent

the Greek economy as a static world, characterized by technological stagnation and

an ideal of self-sufficiency. But was that really the case? It is certainly what one

might think, reading ancient history sources that set such

a high value upon the

autourgos

, the citizen who worked on his land with his own bare hands within the framework

of direct exploitation. Yet that representation corresponds only partly to the reality.

In plenty of cities, the majority of citizens did not possess a property large enough

to assure the viability of such an ideal of self-sufficiency. In Athens, the only

city for which it is feasible to guess at a few figures, fewer than one citizen out

of three was in a position to live off his own land. Close on two-thirds of the civic

population either owned no land at all or else not enough for them to live off; most

citizens owned plots of land less than one hectare in area (that is, less than 2.5

acres) and were consequently forced to engage in other activities, as craftsmen or

as wage-earning agricultural laborers, in order to make a living.

2

So only a fraction of the citizen population lived off its land, a number that corresponded

to the number of those who, in the fifth century, belonged to the census class of

zeugitae

. To these should be added a tiny elite composed of large-scale landowners, such as

Cimon and Pericles—probably no more than one thousand individuals in all—who owned

estates of over 20 hectares (that is, 50 acres), which were in many cases run by specialized

managers (see later).