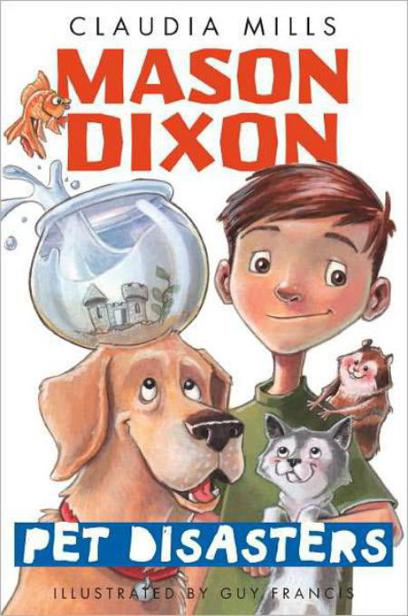

Pet Disasters

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2011 by Claudia Mills

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Visit us on the Web!

www.randomhouse.com/kids

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools,

visit us at

www.randomhouse.com/teachers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mills, Claudia.

Mason Dixon : pet disasters / by Claudia Mills. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

Summary: Nine-year-old Mason’s parents keep trying to get him a pet, but until he and

his best friend Brody adopt a three-legged dog, he is not interested.

eISBN: 978-0-375-89958-4

[1. Pets—Fiction. 2. Dogs—Fiction. 3. Best friends—Fiction. 4. Friendship—Fiction.]

I. Title.

PZ7.M63963Mak 2011

[Fic]—dc22

2010029724

The illustrations were created using pen and ink.

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

To Jack and J. P. Simpson, editorial consultants

1

Mason Dixon didn’t mean for his pet goldfish to die. Really, he didn’t.

But he couldn’t honestly say that he was brokenhearted about it, either.

“Mom!” Mason hollered, staring down at the glass bowl where Goldfish lay floating on the still surface of the water. “Mom!”

He found her in the family room sorting socks. All of Mason’s socks were brown, but his mother sorted them, anyway, according to how worn the heels were. Mason didn’t like it if one sock was thicker around the heel than the other one.

“Mom?”

She looked up from her sorting.

“Mom. Um—I think Goldfish is dead.”

“Oh, Mason!”

He followed her back upstairs to his bedroom, stumbling on one step to keep up with her as she ran. Did she think that if she got there in the nick of time, Goldfish could be saved through CPR?

Mason wasn’t sure how long Goldfish had been lying there. The last time he had stopped by to hang out with Goldfish for a minute or two had been that morning, and now it was midafternoon. Goldfish had seemed fine then. Or as fine as he ever had.

“Oh, Mason,” she said again as together they gazed down at Goldfish’s motionless little body. “Your first pet!”

Mason tried to look sad. He

was

sad, sort of. Poor Goldfish hadn’t had much of a life, swimming around in his bowl all day, in and out of his plastic underwater castle. In, out, in, out. Still, it was the only life Goldfish had had.

“How could he just die like that?” Mason’s mother asked, twisting the brown sock she held in her hand.

“Maybe he was old,” Mason suggested. He didn’t know how to tell if Goldfish was young or old. He didn’t even know how to tell if Goldfish was a boy

or a girl. Mason had always thought of Goldfish as “him,” but he didn’t know for sure.

“We’ve just had him a week!” his mother wailed. “I don’t see how a perfectly healthy goldfish could die in just a week.” Then her face brightened. “Maybe we can take him back to the pet store and they’ll give you another one! They must have some kind of guarantee for customer satisfaction.”

Mason must have looked upset, because she continued, in a gentler voice, “Mason, I know there will never be another Goldfish. Goldfish will always have a special place in your heart. But we can find a fish that looks as much like him as possible. We can even call the new fish Goldfish, if you want. Not that I ever thought that was such a good name.”

Mason didn’t know how to tell her.

“Mom. I don’t want a new goldfish.”

“But, honey—your father and I talked about this. You’re an only child. An only child should have a pet to talk to, to love. It was so good for you to learn how to take care of Goldfish.” She paused. “You did feed him every day, didn’t you?”

“Yes! I fed him twice a day, just like the man at the pet store said.”

“

Twice

a day?”

“Yes!” Mason was getting angry. She didn’t need to look at him like he was some kind of fish murderer.

“Mason,” she said. “The man said to feed him

once

a day.”

Had he? Mason had to admit that he hadn’t really been listening to all the man’s instructions about everything from how big of a bowl to buy for Goldfish to how often they were supposed to clean it. Besides, who ate once a day? Nobody Mason had ever heard of. Mason himself was hungry every fifteen minutes.

“That’s how he died, then,” Mason’s mom said, giving him an accusing look as she crumpled Mason’s brown sock for emphasis. “Overfeeding. Fish can die from overfeeding.”

So he

was

a fish murderer. But he hadn’t meant to be.

He’d be glad if Goldfish could come back to life and start swimming around in his bowl again.

Especially if the bowl were in somebody else’s house.

The goldfish, in Mason’s opinion, was just one more in a long series of bad ideas his parents had had about how to raise him. They always meant well. He had to give them that. But the history of the world was probably filled with bad ideas thought up by well-meaning people.

Take his name, for instance. That was bad idea number one. His father’s last name was Dixon, and his mother’s last name had been Mason, which could be either a first name or a last name. His parents had thought it was a good idea to make it Mason’s first name. Besides, there was a famous line called the Mason-Dixon Line between the North and the South during the Civil War, so his parents thought

the name had a nice ring to it. They thought it was an unusual and distinctive name that still had a pleasingly familiar sound to it.

Basically, Mason had been named after a

line

.

Luckily, at school they wouldn’t study the Civil War until fifth grade, so other kids didn’t know about the Mason-Dixon Line yet. Mason knew that when they learned about it, year after next, he would suddenly have a new nickname that would stick with him for the rest of his life.

Hey, Line!

they’d say.

How’s it going, Line? Ha, ha, ha, ha!

So that was something to look forward to.

Mason’s parents, especially his mother, thought that variety was another good idea. (His father went along with her, but Mason could tell that usually his heart wasn’t in it.) She liked to try out new recipes from around the world: African peanut stew, a Brazilian potato salad that had olives in it. Both of those had been stunningly bad ideas. Peanuts were supposed to make peanut butter, not peanut

stew

. And olives were a bad idea even before they were mixed with cold potatoes and something called capers (another bad idea).

Mason’s mother liked variety in what she wore as well. She might wear a sari from India, or a poncho

from Mexico, or something odd that she had knitted herself. Mason liked to wear jeans or shorts in a neutral color, a solid-colored T-shirt, and brown socks. Mason loved brown socks. Brown socks went with everything. White socks looked strange with long pants. Black socks looked strange with shorts. But brown socks always looked unremarkable. Brown socks didn’t call attention to themselves. Brown socks were quiet, ordinary, calm, and predictable.

Unlike a comical name, African peanut stew, hand-knit Mexican ponchos, and pet goldfish who died, brown socks were a good idea.

Mason’s best friend, Brody, came to Goldfish’s funeral. Goldfish funerals were the kind of thing Brody loved and Mason hated.

Mason and Brody had been best friends since they were two years old. They lived next door to each other and had been in classes together ever since preschool. One day, in their first year at Little Wonders, Brody was absent and Mason walked up to another boy and asked him to play pretend: “Let’s pretend you’re Brody.” It was Mason’s mother’s favorite story to tell about Mason. Mason was tired of hearing it.

Goldfish was going to be buried in the toilet. Not buried, exactly, but flushed away to the great fishbowl in the sky.

Mason had thought maybe he could just do a private flushing, without too much fuss and bother, but he could tell that his mother would think he was heartless if he suggested it. So he had invited Brody, who adored fuss and bother. Now that it was summer vacation, they were at each other’s houses every single day.

“Should I wait for Dad to get home from work?” Mason asked his mom.

Mason’s dad worked for the city government in an office downtown. His job had something to do with roads. Whenever there was going to be road construction somewhere, Mason’s father was always the first one to know about it, glad that he could choose his driving route to avoid a detour. He wore a tie to work and carried a briefcase, but Mason had never seen him put anything in the briefcase or take anything out of it.

“No, I think Dad’s going to be late today.” She hesitated. “He has a—a couple of errands he needs to run. And I have a conference call I need to prepare

for. But I’m glad Brody will be here with you.”

So Mason and Brody did the funeral all by themselves. Brody was wearing a black T-shirt, turned inside out.

“So the words on it don’t show,” Brody explained. “That’s more respectful for a funeral.”

Mason looked down at his own green T-shirt. It didn’t have words on it; Mason would never wear a shirt that had words on it. Still, it might be a bit bright for a funeral. He didn’t feel like changing it.

“Anyway, this isn’t really a

funeral

,” Brody said. “People don’t have funerals anymore, my mother told me. They have celebrations of life. So this is a celebration of the life of Goldfish.”

“What do people do at celebrations of life?” Mason asked. He wasn’t in the mood for anything overly festive.

“They make speeches. And sing.”

Two of Mason’s least favorite activities in the world.

“Don’t worry,” Brody reassured him. “I’ll make the speeches. I’ll do the singing. I’ll do the whole thing. Is anybody else coming, besides Albert?”

Albert was Brody’s goldfish, still completely alive

even though Brody had gotten Albert a whole week before Mason got Goldfish. That was how Mason’s parents had gotten the idea of a goldfish for Mason. The pet Brody really wanted was a dog, but Brody’s father was desperately allergic to any pets with fur or hair. Still, Brody loved Albert and thought he was better than no pet at all.