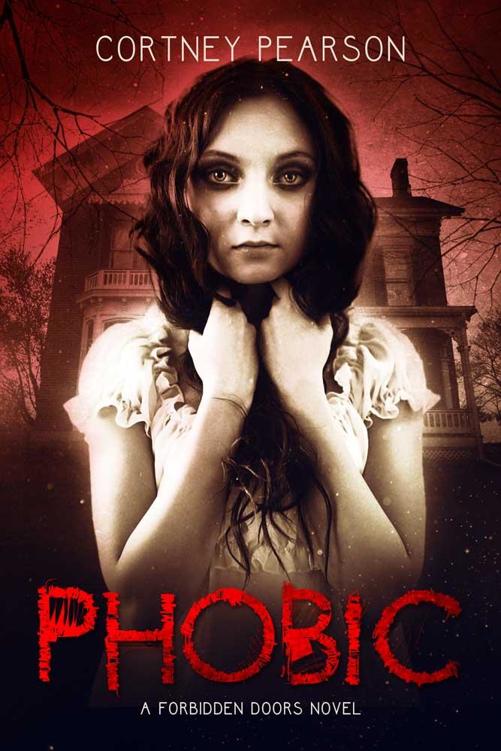

Phobic

Authors: Cortney Pearson

For all my boys

…even death has some antidote to its own terrors.

–

Bram Stoker,

Dracula

W

hen I was six years old, I found the man my mother murdered stuffed under a trap door in our kitchen. The smell gave him away.

Police swarmed the house, which—uncharacteristically—made no creaking groans of protest at having that many

outsiders

in it. It was almost like the house knew Mom’s secret and wanted her to get caught.

The roof above me rasps now, like it’s being racked by a fleeting storm, but I grip the clarinet in my hands and glance at the stationary leaves and blue sky outside. Another moaning rasp resounds, nearly overriding the chime from the vintage clock with its swinging pendulum. That chime tells me I have thirty minutes before school starts. Time to get going. Except no matter how creeped out I am in my house, school is the last place I want to be.

Holding my clarinet so I don’t bend its silver keys, I separate the wooden pieces, place them in the case, and snap the clasps shut. Silence clouds my parents’ room in place of the sultry tones I’d been pushing out minutes before.

I stiffen, more aware of the walls around me. They’re like people I have to make my way through, a pulsing crowd of wood that inverts depending on my movements, tilting and nosing in. When I stop to notice them, they look away; motionless, as if they didn’t know I was there.

Just walls

, I tell myself, feeling a presence on my back like my every move is being calculated.

I still see traces of my mother everywhere I look. If I didn’t know she was in prison, I’d think she was the one haunting my house, offering hollow wails in the early hours of morning, when day is breaking but dark things still have time to creep.

Clarinet case in hand, I scurry through the door at the top of the landing labeled

Staff Only

and head down the narrow stairs that once gave servants a direct line into the kitchen below. Like servants back then weren’t good enough to use the same stairs everyone else did.

The dining room is attached to the kitchen, with a thick archway separating one from the other. Dark wainscoting climbs the lower half of the walls and meets speckled wallpaper the rest of the way up. An elegant chandelier dangles over the table littered with my older brother, Joel’s, papers.

I grab a Pop-Tart from the narrow, floor-to-ceiling cabinet. The music I’d been practicing plays in my head like a CD on repeat, and nerves strum beneath my skin. My scholarship audition—my chance to get out of this house next summer—is tomorrow, and I wish my mom could be there.

I tried not to mind that she wasn’t at district solo competition last year, when as a freshman I beat a senior. Or that Mom isn’t around to show me the kind of girl-stuff other daughters learn. I’ve got my older brother, Joel, but he knows as much about putting makeup on as I do. And when I got my period I wasn’t about to ask him how to put in a tampon.

It’s why I like to practice in her and my deceased father’s bedroom. I like to think that even from prison, my mom can hear me play.

“I just have to make it through school,” I tell myself, ripping open the crinkly wrapper. The striped walls above the wainscoting give several creaks like a rocking chair screeching back and forth, urging me to stop talking. I shudder at the sound and keep going anyway. “Two more days ‘til the audition. I can do this.”

The TV flips on of its own accord. I jolt and hurry to shut it off, but not before I catch a glimpse of the news anchor; the mother of my archnemesis, Sierra Thompson. It wasn’t enough in sixth grade when Sierra got boobs and I instead got break outs, but since then Sierra has persisted to remind me how lame I am compared to her, how much better than me she is at everything.

I push a stack of Joel’s blue bound depositions aside enough to perch on the table and watch the window, waiting for my ride. After stealing a quick glance at the clock hanging above the old iron fireplace, I pull out my phone to scan through Facebook, not really reading the timeline. More like a nervous habit to kill time. The TV flicks on once more, striking my back with its unexpected sound.

“Enough already,” I grumble, hopping from the table to shut it off, but not before Sierra’s mom smiles and tosses her silky hair in the exact way her daughter does. I take a bite of strawberry, flat-pastry goodness and smush the power button.

Seeing her only reminds me of the argument I had with Joel the night before. How I told him I was dropping out of school and skipping straight to college, followed by lots of yelling and then Joel saying, “Maybe things wouldn’t be so bad if you actually tried making friends, Piper.”

Puh.

It was hard enough on us both when our dad died ten months ago, but I think Joel has struggled with the whole being-my-guardian thing since then. He barely turned twenty-five, is still in law school, and interns for a law firm. I’m sure he’s not thrilled having to watch out for his kid sister.

I’m really not that different from Sierra and the other kids who exist to make my life miserable. So what if my house is freaky-haunted and I have a few pimples? That doesn’t give them the right to single me out.

I give Facebook another glance and see Sierra’s name and some post about the curtains in her bathroom. I’m not even sure how we ended up being FB friends in the first place. One of those I’m-only-friending-you-because-I-know-you-exist situations, I guess. I’ve actually tried being her friend in real life, but after several separate instances where I’d laughed at things she’d said, only to find out later that I was the joke, I decided she wasn’t worth the effort.

My best friend Todd’s red pickup appears at the curb, spewing exhaust like the truck has a cigarette up its backside. I jerk up. My pulse kicks at the sight of him. That’s been happening a lot more lately, my insides flaring up and doing some sort of spastic dance whenever I catch sight of his alluring smile and dark curls.

Leaving the second Pop-Tart on the table, I stuff my phone in my pocket and snatch up my backpack and clarinet case. I dart past the round, velvet-topped table in the wide hallway to the front door.

I reach for the knob. It won’t turn.

Heart pounding, I try again. One way, then the other.

Chick. Chick

. The lock mechanism is vertical. The door

isn’t

locked.

“Not now,” I say under my breath. “Please not now.”

The hairs at my nape skulk up one by one until they all stand on end. My wrist flicks, and the obstinate knob makes the same

chick chick

sounds. The eerie feeling spreads down the length of my arm, making the knob cold under my touch. What is going on? I’m used to my house doing strange things, but why won’t it let me out?

Todd’s horn honks again and I shake the door handle.

“Don’t do this,” I say to the oval, pieced glass, setting my case on the rug to use both hands. I wrestle with the knob until a sound startles me, so soft I barely catch it. Crinkling static, like an AM radio out of signal. My ankle rolls in these wedges, and I support myself on the carved hat stand beside a large mirror.