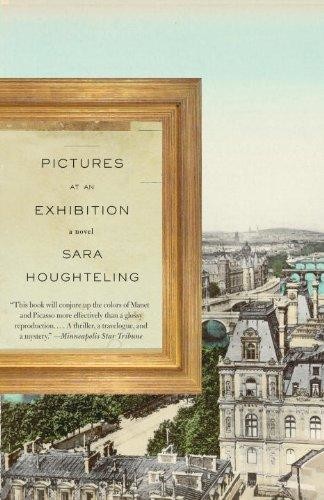

Pictures at an Exhibition

For Fiora and James Houghteling

and

Florence and Burton Waisbren

“Only in a house where one has learnt to be lonely does

one have this solicitude for

things.

“

—Elizabeth Bowen,

The Death of the Heart

PART ONE

Almonds

ÉDOUARD MANET

, oil on canvas (21 times 26 cm), 1861-1871

Chapter One

I

N THE TWILIGHT OF MY LIFE, I BEGAN TO QUESTION

if my childhood was a time of almost absurd languor, or if the violence that would strike us later had lurked there all along. I revisited certain of these memories, determined to find the hidden vein of savagery within them: the sticky hand, the scattered nuts, the gap-toothed girl grasping a firecracker, a cap floating on the Seine, flayed legs swinging between a pair of crutches, the tailor and his mouthful of pins. Some of these were immediately ominous, while others only later revealed themselves as such. However, whether or not another boy living my life would agree, I cannot say.

Of the humble beginnings from which my father built his fame, I knew only a few details. My grandfather, Abraham Berenzon, born in 1865, had inherited an artists’ supply store. He sold tinctures, oil, canvases, palettes and palette knives, miniver brushes made from squirrel fur, purple-labeled bottles of turpentine, and easels, which my father described as stacked like a pile of bones. The shop was wedged between a cobbler's and a dressmaker's. Artists paid in paintings when they could not pay their bills. And as Renoir, Pissarro, and Courbet were far better with paint than with money, the family built up a collection.

When the value of a painting exceeded the price of its paint, Abraham sold it and invested the money with the Count Moïses de Camondo, a Jew from Istanbul with an Italian title and a countinghouse

that he named the Bank of Constantinople. Both men loved art, and they were fast friends. By 1900, Abraham could purchase an apartment on rue Lafitte, near Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, in a neighborhood known as the Florence of Paris. Soon afterward, Moïses de Camondo recommended that my grandfather invest in the railroads. Coffers opened by the beauty of paint were lined with the spoils of steel, steam, and iron, and my grandfather did not have to sell any more of his paintings.

As a teenager, I often passed by rue Lafitte and imagined the family home as it had once been, as my father had described it: each picture on the grand salon's walls opening like a window—onto a wintry landscape, a tilted table with rolling apples, a ballet studio blooming with turquoise tulle. The salon's chandelier shone onto the street through windows which, as was the case across the Continent, were made from high-quality crystal. On sunny afternoons, Grandfather's gallery was so ablaze with prismatic light that schoolchildren returning home for lunch thought they saw angels fluttering down rue Lafitte. They reported their sightings to the choirmaster at Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. When he could no longer bear to tell any more youngsters that they had not seen angels but just rainbows, and from a Jew's house no less, the choirmaster hinted to some older boys that perhaps they should break the windows, which they did.

At least that was how my father explained the attack on his childhood home in July of 1906. Then again, Dreyfus had just been exonerated, and there were many such outbursts across Paris. Abraham had followed the trial closely, nearly sleepless until the Jewish captain's verdict was announced. Two days later, hoping to spare a dog that ran into the road, he drove his open-roofed Delage into an arbor of pollarded trees on avenue de Breteuil. My sixteen-year-old father, Daniel, was pinned between the tree trunk and the crushed hood as Abraham expired beside him. From then on, my father walked with a limp, which eight years later exempted him from service in the Great War. So whether he was lucky or unlucky, I could not exactly say.

In 1917, my father purchased the building at 21, rue de LaBoétie, after my mother Eva agreed to marry him. For this young Polish beauty, whom he hardly knew, and who spoke comically stilted

French, he bought a house in a neighborhood known for its tolerance of the creative temperament. Yes, as if in anticipation of the utter bleakness that would eventually follow, that block was home not only to my father the collector and my mother the virtuoso pianist, but also to a choreographer renowned for his collaboration with Diaghilev; the Hungarian trumpeter most preferred by European conductors to perform the second of the

Brandenburg Concertos;

a sculptor known for his works in bronze and his clamorous machines; and, three years later, though without the same fanfare, me.

From the well of my early childhood, only one half-lit event emerges: I am in the forest and a small girl shares a sweet bag of nuts with me. We dance on the mossy floor, and she holds my sticky fist in her own. Until late in my life, I supposed that the little girl in the white dress had been a dream, invented sometime in the crepuscular years before my seventh birthday. I remembered nothing at all before 1927, when Lindbergh landed at Le Bourget, on an airfield lit brighter than day. This absence of memory was natural, I imagined. I had no siblings with whom to compare my experience and was loath to press others into discussing my youth.

UNLIKE HIS OWN FATHER, MINE MAINTAINED NO PAR-

ticular attachments to the paintings that found their way into his possession upon Abraham's death. Father sold this collection as the first exhibition of the Daniel Berenzon Gallery in the early 1920s. He explained that, at the time, he had been under the influence of the German philosopher Goethe. “Remember the

Theory of Colors

, Max,” he said, as he paced the gallery. “When you stare steadfastly at an object, and then it is taken away, the spectrum of another color rises to your mind's eye. This second image now belongs to the mind. The object's absence or presence is irrelevant. They're all up here”—he tapped his head—”so why worry about them out there?” He gestured to the carmine and gold gallery walls. “You'll have a museum of the mind.”

And for him this was true. To hear my father describe the paintings he had sold—which I thought of as lost—was as if their watery

images, quivering and illuminated, were projected on the dark walls of the gallery from a slide carousel. These pictures possessed a certain patina—of regret, of time, of absence, of value—which lent my father's descriptions a deeper beauty than I had been able to see when the paintings hung before me.

Indeed, my father was among a tiny group, the heirs to the patron spirit of Catherine de Médicis and the savoir faire of Duveen or Vollard, whose genius was not in the handling of paint itself, but in the handling of men who painted. They encouraged the artists’ outrageous experiments so that they could paint without fear of financial ruin. They were not just rug merchants and moneymen. They were as devoted as monks to the beauty of their illuminated manuscripts. Or so my father said, in his most rhapsodic moments. And I believed him.

Pablo Picasso was my father's most famous artist, and he too came to live on rue de La Boétie, at number 23. When my father passed below on the street, Picasso would stand in the window and hold up canvases for my father's approval, and approve he always did. Father encouraged the Spaniard's experiments, understanding that Picasso's genius resided not in a single style but in his ability to reinvent himself. He was, Father said, our Fountain of Youth. Since Monsieur Picasso's art would never grow decrepit or stale, neither would Father and neither would their glorious world of paint. Yet Father kept not a single Picasso in our family collection; what hung over our dinner table would likely be sold the next week. Our walls were never bare, nor were they familiar. “We're trying to give what we have away,” Father said. Though he hardly gave the paintings away, I wondered, sometimes, if he felt that he had.

Beginning in my earliest years, each night before Father locked the doors to the art gallery, I was called downstairs from my bedroom and, with my eyes closed, was told the name of a past exhibition and made to recite each painting's artist, title, and composition: a Morisot

Woman in White

looking like an angel with the dress slipping from her shoulder; the Vuillard odalisque

Nude Hiding Her Face

from 1904; an iridescent 1910 Bonnard,

Breakfast

, of woman, jam, and toast.

After we reviewed the present exhibition, we would recollect past ones, of Sisley and Monet's winter scenes; Toulouse-Lautrec's portraits on cardboard with low-grade paint; the occasion on which Father had furnished the exhibition rooms with rococo settees and ormolu chiffoniers and then hung above them the most wild drawings by Braque, Miró, Gris, and Ernst, so as to indicate that modern art could indeed decorate a home. Though Father's clients purchased mostly for this purpose, privately he scoffed at those who arrived with a scrap of drapery when choosing a painting. “The artist is an aristocrat, Max,” my father told me. “He has suffered for his art. And yet still he is generous, because he offers us a new language that permits us to converse outside of words.”

I often wished that Father would not converse outside of words but, rather, raise other subjects during these meetings and guide me on boyhood matters, such as girls in sweaters or my birthday choice of alpine skis. Once or twice, I sensed that he tried to. I waited patiently, nearly holding my breath so as not to break the spell when Father began, “Over the years, I have wanted to tell you—” But this sentence, though repeated, was never finished, and eventually I gave up hope. Still, the nightly recitations were treasured occasions with my father, a man for whose attention many people, including my mother, had to fight.

In my memory of those nights in the gallery with pictures orbiting around me, my father is splendid, luminous even. He had a brushy mustache, a neat chin, and a slim neck. He wore a white collar and a long tie the shade and sheen of obsidian: a lean, angular man, as if he had stepped out of a canvas by Modigliani and, dusting the paint from his dinner jacket, taken his place against the gallery's doorjamb. He parted his black hair on the side and his eyebrows looked penciled in. His face might have seemed too small were it not for the significant ears, the plane of his cheekbones, and his long, sloping nose.

As pictures were hoisted to the walls and then lowered, President Doumer was shot dead at a book fair, the Lindbergh son was kidnapped, and America choked in a cloud of dust. All of France seemed

to be on strike. By eleven, I was expected to discuss various genres and artists.

“On still lifes,” my father began, and walked to the back of the red divan.

“The lowliest of genres,” I said. “Courbet painted his in prison.”

“Yes.”

“With landscape painting only slightly superior.”

From upstairs, we heard Mother singing along with her piano playing. Sometimes she sang the orchestra parts to Brahms or Beethoven, or hummed along with the piano melody so as not to lose her place in it as her fingers whirled through their steps. If Father was rehearsing the art of recollection with me, we both knew that Mother, with her hundreds of hours of music committed to memory, reigned supreme. Whatever sensitivity Father and I might have possessed, Mother surpassed this, too: she heard sharps in the opening and closing of my dresser drawers and an unpleasant A-flat when the telephone rang. She thanked Father for choosing an automobile whose motor played an excellent C. When Mother traveled to Zurich and London to perform, I was left in the care of our housekeeper, Lucie, and our chauffeur, Auguste. Both loved music and, fortunately, both loved me.

I grew from a boy in pajamas to a young man who lit his father's cigarette before smoking his own. The fixed point in Father's collection was Manet's

Almonds

, painted in the years between 1869 and 1871. It was the one painting from my youth that had never left 21, rue de La Boétie, not in the first auction nor in the dozens that would follow. When Father bought Manet's

The Bar at the Folies-Bergère

before lunch and sold it by dinnertime to a British sugar magnate,

Almonds

stayed behind; Picasso's

The Family of Saltim-banques

was shipped to New York, but

Almonds

stayed behind. Even when Mrs. Guggenheim was on her campaign, as she told Father, to buy “a picture a day,”

Almonds

remained. Father claimed that no one offered him the right price for it, though later I came to understand otherwise. Father loved the painting, though he would not say why, except that it was painted by a humbled man nearing the end of his life, when Manet's legs were weak with syphilis and the artist could

no longer stand at his grand canvases, as he had done with

The Execution of Maximilian

or

The Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

The man whose life had begun to still began to paint still lifes. I did not consider Manet's

Almonds

beautiful. I found it morbid and sad to look at in the morning hours, when the light was clear and bright. In comparison to Cézanne, who often had to replace his pyramids of apples with wax versions because the real fruit rotted after a fortnight of study, Manet's almonds were the ones that had been passed over, deemed too inferior to eat, painted by someone who'd had his fill. Still, I averted my eyes from the painting with difficulty.