Pie and Pastry Bible (108 page)

Read Pie and Pastry Bible Online

Authors: Rose Levy Beranbaum

ASSEMBLE THE BISTEEYA

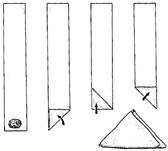

Lay the stack of fillo on the counter and keep it well covered with plastic wrap and a damp towel to prevent drying. Remove 1 sheet of fillo and place it on the work surface. Brush it lightly with the butter, using about 1 teaspoon, starting around the edges where it will dry out the most quickly and then dappling it lightly all over (or spray it lightly with olive oil). Sprinkle the fillo with 2 teaspoons of the finely chopped nuts and lay another sheet of fillo over it. Brush it lightly with butter (or spray it lightly with olive oil). With a sharp knife and a long ruler, cut it lengthwise into 4 strips. Place a rounded tablespoon of the bisteeya mixture near the bottom of each strip. To shape each triangle, fold the bottom of the dough over by lifting the right corner and bringing it to the left edge so that it partially covers the filling. (The next fold will cover the filling completely.) Continue, folding the strip as though folding a flag, always maintaining the triangle. Tuck under or trim the end. Place the finished triangle, seam side down, on a greased cookie sheet and brush the top lightly with butter. Repeat with the remaining filling and fillo, placing the triangles about ½ inch apart.

Bake the bisteeya for 15 to 20 minutes or until golden brown. Serve hot, warm, or room temperature, sprinkled with the remaining nuts and the sugar and cinnamon. (Reheat in a preheated oven to 300°F. for 7 minutes.)

VARIATION

LARGER BISTEEYA

(FOR A FIRST COURSE) Butter eight 5- to 6-ounce ramekins (about 3 by 1½ inches) and line each with 2 sheets of fillo, letting the overhang drape over the sides. Fill each mold to the top and fold the fillo over the filling. Brush the top with melted butter. Bake for 20 minutes or until golden. After baking, sprinkle with the powdered sugar, cinnamon, and nuts.

STORE

Unbaked, refrigerated, up to 24 hours; frozen, up to 3 months. To freeze, wrap the cookie sheets with plastic wrap and then foil, or freeze the triangles on the baking sheets until hard, then transfer to a container.

STRUDEL

S

trudel. What an evocative word! In German, it means whirlpool. In pastry, it means heaven—the thinnest leaves of flaky pastry wrapped around warm, cinnamon-laced slices of apple, served with whipped cream (schlag in German). The very word seems to elicit sighs of nostalgia from people who have eaten the real thing. And anyone who has will never be content to substitute commercially produced fillo, which lacks both the tenderness and finesse.

Because strudel always seemed like a magical dough to me, I was terrified of it. It took a trip to Austria to overcome my strudel phobia. My friends Sissi Pizutelli and Gabriele Wolf from the Austrian tourist office in New York City assured me that since my paternal grandmother was Austro/Hungarian, I had strudel-making skills in my blood! Bolstered by their confidence in my ancestry, I made strudel in restaurants and bakeries from Innsbruck to Vienna, with some of Austria’s finest chefs and pastry chefs. In Innsbruck, I had my first lesson with pastry chef Klaus Huber, who, in true pastry tradition, had everything written out and weighed. Then on to the head chef, Elmar Steinberger, to learn many varieties of delicious savory strudels. In Bad Ischl, at Zauner (the finest bakery I have every encountered, where I had the privilege of being the first outsider to work in their kitchen), pastry chef Alfred Schachner had me make a strudel by hand and without weighing or measuring anything just to see how easy it is to do by feel. In Vienna, at the Hilton, which produces some of the best strudel anywhere, pastry chef Andreas Eckstein made me throw the dough up in the air the way you would pizza (it landed on my chest—much to the amusement of all the chefs, but it sure broke the ice). In the kitchen at Hotel Sacher, I watched two bakers stretch strudel dough over an eight-foot table. But it really wasn’t until I made strudel entirely on my own in my own kitchen that I was convinced that strudel making, once learned, is both easy and delightful. Stretching a 3-inch ball of silken dough into a

gossamer four-foot-long translucent sheet gives one a sense of accomplishment unequal to any other in baking. And strudel dough actually benefits from heat and humidity, making it the ideal pastry for summer.

Though making and rolling out strudel is practically child’s play, the secret to success is, once again and here more than ever, the

type of flour.

In order for the dough to stretch without breaking and forming many holes, it needs to contain not merely gluten-forming protein but a specific kind of protein that has extensibility, i.e., the ability to stretch. This quality changes slightly with each harvest of wheat. In bleached flour, most of this protein has been completely destroyed, which will result in a dough that is not as smooth, is very difficult to stretch, and is full of holes. (Equal weights of both bleached and unbleached Gold Medal flour required the same amount of water, indicating that the gluten-forming protein content was the same.)

King Arthur regular flour is the easiest flour to work with, resulting in a dough that can be stretched so thin, and virtually without holes, as to become indistinguishable to the touch from the soft cotton sheet beneath it, but its higher protein content makes it slightly less fragile and dissolving when eaten. Doughs made with national brands of bread flour, which have only a slightly higher protein count than King Arthur, did not stretch as far or with as few holes.

Gold Medal unbleached flour has a lower protein content than these but even greater extensibility. I was able to stretch a dough made with it to fifty-four inches, but it dried out so quickly it almost disintegrated as I brushed it with butter. (I, therefore, do not recommend stretching the dough beyond forty-eight inches.) Dough made from Gold Medal Flour will have a tendency to tear (I did stretch a dough to forty-nine inches without a single hole on a rainy day), but a few holes really don’t matter because since rolled strudel has so many layers, there aren’t enough holes once it’s rolled for the filling to leak through. Moreover, the baked strudel will be as crisp and flaky as one made with King Arthur flour, the most gossamer and dissolving of all, making it my personal first choice. Using this flour, I felt that my strudel was as good as any I had made or tasted in Austria—and more tender. For first-time strudel makers, I recommend using King Arthur flour, the results of which seemed identical to the Austrian strudel. Some bakers will even prefer the slightly firmer bite. Also, when you start out, it’s important to have successful results to build confidence.

STRUDEL DOUGH

(Master Recipe)

S

trudel dough takes less time to make than pie dough. It takes only minutes to mix and knead and then about ten minutes to stretch. Wrapping it around the filling and shaping it into a roll is the easiest part of all. Making strudel dough is fun, but

only

if you use the recommended flour! With this recipe, you can make just about any strudel and the pastry will be crisp, flaky, and dissolving. A series of step-by-step drawings follows the instructions. But if you are willing to forgo the pleasure of making your own dough, the simple technique for using commercial fillo dough in its place is on page 393.

| | MAKES: 8.7 OUNCES/248 GRAMS OF DOUGH, ENOUGH FOR ONE 16- TO 18-INCH-LONG STRUDEL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| INGREDIENTS | MEASURE | WEIGHT | |

| VOLUME | OUNCES | GRAMS | |

| *You will also need a little oil to coat the finished dough and plate. | |||

| †See page 629; you will need to start with 8 tablespoons (4 ounces/113 grams). There will usually be about 1 tablespoon left over. | |||

| unbleached all-purpose national-brand flour, such as King Arthur’s regular flour or Gold Medal | approx. 1 cup (dip and sweep method) | 5 ounces | 142 grams |

| salt |  teaspoon teaspoon | • | • |

| warm water |  liquid cup + approx. 1 teaspoon liquid cup + approx. 1 teaspoon | 2.75 ounces | 78 grams |

| vegetable oil | 4 teaspoons* | • | • |

| To Brush on the Dough melted butter, preferably clarified,† warm or room temperature | 6 tablespoons | 3 ounces | 85 grams |

EQUIPMENT

A 36- to 48-inch-wide table, preferably round, covered with a clean sheet or tablecloth rubbed with a little flour, and a 17- by 12-inch cookie sheet or half-size sheet pan, buttered

ELECTRIC MIXER METHOD

In the bowl of a heavy-duty stand mixer, preferably with the dough hook attachment, place the flour and salt and whisk them together by hand. Make a well in the

center and pour in the cup of water and the oil. On medium speed, mix until the dough cleans the sides of the bowl. If the dough does not come together after 1 minute, add more water, ½ teaspoon at a time. Don’t worry if it becomes sticky; adding more flour to make it smooth will not affect the strudel’s texture. Remove the dough to a counter and knead it lightly for 1 to 2 minutes or until smooth and satiny. It will be a round ball that flattens on relaxing.

cup of water and the oil. On medium speed, mix until the dough cleans the sides of the bowl. If the dough does not come together after 1 minute, add more water, ½ teaspoon at a time. Don’t worry if it becomes sticky; adding more flour to make it smooth will not affect the strudel’s texture. Remove the dough to a counter and knead it lightly for 1 to 2 minutes or until smooth and satiny. It will be a round ball that flattens on relaxing.

Pour 1 teaspoon of oil onto a small plate and turn the dough so that the oil coats it all over. Cover it with plastic wrap and allow it to sit at room temperature for at least 30 minutes, or refrigerate it overnight.

HAND METHOD

On a counter, mound the flour and sprinkle it evenly with the salt. Make a well in the center and add the oil. Gradually add the cup water in 3 or 4 parts, using your fingers and a bench scraper or spatula to work the flour into the liquid until you can form a ball. If necessary, add up to 1 teaspoon more water. Knead the dough until it is very smooth and elastic and feels like satin, about 5 minutes, adding extra flour only if it is still very sticky after kneading for a few minutes. Oil and allow it to rest as above.

cup water in 3 or 4 parts, using your fingers and a bench scraper or spatula to work the flour into the liquid until you can form a ball. If necessary, add up to 1 teaspoon more water. Knead the dough until it is very smooth and elastic and feels like satin, about 5 minutes, adding extra flour only if it is still very sticky after kneading for a few minutes. Oil and allow it to rest as above.