Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (107 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

He has lost twenty dead, forty-four wounded. The Indians scalp the corpses, loot their belongings, and are prevented from killing the wounded only by McDouall’s stern discipline.

Holmes’s body, stripped, is found by his black servant who hides it under a covering of bark until a truce party recovers it the following

day. It is taken aboard

Lawrence

which, with the gunboats, is returning to Detroit loaded with one hundred sick and wounded and a portion of the soldiers. But Sinclair and Croghan remain on Lake Huron with

Niagara, Tigress

, and

Scorpion

, determined to blockade the lake. If the Americans cannot take the British stronghold by force, they intend to starve it into surrender.

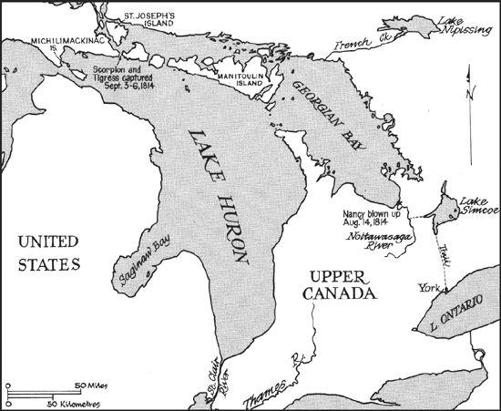

NOTTAWASAGA BAY, GEORGIAN BAY, LAKE HURON, AUGUST 13, 1814

Sinclair’s reduced fleet anchors in the small harbour, debouching men and guns to attack the British supply base a mile or so up the Nottawasaga. In this way he hopes to strangle the supply line to Mackinac Island. A prisoner from a British gunboat, captured during the excursion to St. Joseph’s Island, has described this secret route, which runs from Little York to Lake Simcoe, across a short portage into the Nottawasaga River, and thence down to Georgian Bay. Sinclair has also learned that the British sloop

Nancy

is expected to take on supplies for Mackinac deposited earlier at the river’s mouth. What he does not know is that Lieutenant Miller Worsley of the Royal Navy has been alerted to their presence.

When McDouall saw the American fleet hovering off his shore, he realized that he must get word to Nottawasaga to hold back

Nancy

for fear of capture. To carry this message by fast canoe across three hundred miles of treacherous water to the British post up the river he chose a remarkable man, Robert Livingston. An Indian Department courier, Livingston knows every foot of the fur country. He has logged nine thousand miles by canoe in the service of his department. In this War he has been taken prisoner twice, escaped twice, suffered five wounds, two of which have not yet healed. A tomahawk cost him the sight of his right eye, a musket ball is lodged in his thigh, spear wounds have scarred his shoulder and forehead. No matter; he has managed to beat the American navy to the river’s mouth to find the sloop loaded with six months’ provisions, ready to sail. Warned by Livingston of the American

presence on the lake, Worsley and his twenty-one seamen haul the little craft three miles up the narrow, winding river, impeded by overhanging boughs and rocks jutting from the shallow water. They conceal the vessel behind a bald ridge, protected by a hastily built blockhouse and a twenty-four-pound cannon, then await developments.

Their attempt at concealment fails. Sinclair and Croghan can see the vessel’s masts above the ridge. Worsley and Livingston with twenty-one sailors, nine voyageurs, and twenty-three Indians are badly outnumbered by Croghan’s three hundred assault troops. The next day, the Americans hammer at the blockhouse with a four-pounder, to no effect. At noon they unload two howitzers, move them forward under cover, and lob shells into the British position. There is a shattering explosion: a shell has hit the magazine. Worsley leads his men into the forest as a train of powder, previously laid, sputters its way to

Nancy

, blowing up the ship and everything aboard—shoes, leather, candles, flour, pork—all destined for the starving fort.

Sinclair spots a packet flung from the exploding blockhouse—correspondence between McDouall and Montreal. Now for the first time he has an inkling of the island’s desperate condition. He can safely return to Lake Erie with Croghan leaving

Tigress

and

Scorpion

behind, one to hover at the mouth of the Nottawasaga, the other to guard the entrance to the French River, the terminal point on the Ottawa River portage route. If the two schooners do their job, nothing will get through to Michilimackinac. If necessary, he tells

Tigress’s

commander, he may also cruise around St. Joseph’s Island to intercept the great fur canoes of the North West Company. Thus, with total command of the huge lake, the Americans can squeeze the British dry and seize the fur country.

But Sinclair has reckoned without young Miller Worsley who, with his men, has retreated fifteen miles up the Nottawasaga. Here, unknown to the Americans, is another cache of supplies: one hundred barrels of flour, two big bateaux, and the canoe that Livingston brought from Mackinac. On August 18, Worsley and Livingston load

men and provisions into the three craft and set off to row and paddle for 360 miles along the north shore to the British garrison.

Lake Huron, Summer, 1814

Six days later, within eight miles of St. Joseph’s Island, they are greeted by an unexpected sight: the two American schooners,

Tigress

and

Scorpion

, cruising in tandem down the Detour channel, seeking the North West Company’s fur canoes. At once Worsley hauls up his boats, conceals the supplies, crams all the men into Livingston’s big canoe, and as dusk falls slips past the enemy at a distance of no more than one hundred yards.

When he reaches Michilimackinac on August 31, he finds the garrison on half rations, eating their horses and paying ballooning prices to the settlers—a dollar and a half for a loaf of bread. McDouall is more than willing to fall in with Worsley’s bold offer to lead an attack on both American vessels to clear the lake of the enemy.

The next day, Worsley’s force sets off in four bateaux. The naval

commander and his seamen are in one boat. Fifty members of the Newfoundland Fencibles, experienced boatmen and fishermen, occupy the other three. Robert Dickson follows with two hundred Indians in nineteen canoes.

At sunset on September 2, this formidable flotilla reaches the Detour channel. The following day Worsley and Livingston paddle off by canoe to seek the American schooners. They come upon one,

Tigress

, anchored in the channel only six miles away. That night the four bateaux set out, the men rowing with muffled oars. At nine, they see the dark outline of the schooner against the night sky. Two bateaux slip around to the port side, two to the starboard. Worsley is within ten yards of the vessel before he is hailed. He makes no reply. A burst of musket fire and the roar of a cannon follow, but by this time his men have clambered aboard and are fighting hand to hand with officers and crew. It is a short, fierce struggle; every American officer is wounded including the sailing master, Stephen Champlin, Perry’s friend and kinsman, whose thigh bone is shattered, rendering him a cripple for life.

Somebody tries to burn

Tigress’s

signal book, but one of the British seizes it. Now Worsley has the flag code. He sends Livingston off in a canoe to find

Scorpion

. Livingston returns in two hours to report the schooner fifteen miles down channel but beating up toward

Tigress

.

Worsley plans a bold deception. He will keep the American pennant flying, hide his soldiers, dress the officers in American uniforms. The charade is in readiness when

Scorpion

, unsuspecting, comes up and anchors two miles away on the night of September 5.

At dawn, Worsley slips his cable and bears down on the other ship, using his jib and foresail only. His men lie on deck, hidden under their greatcoats. The signal flags deceive the Americans; no officer walks

Scorpion’s

deck. A gun crew, busy scrubbing the planking, pays no attention to

Tigress

until it is within ten yards.

By then it is too late. The grappling-irons are out, the muskets are exploding, men are pouring over the side, seizing the bewildered Americans. It is over in five minutes, to Sinclair’s subsequent mortification.

Thus ends the war on the northern lakes. Mackinac Island is relieved. Lake Huron is again an English sea. The fur country, almost as far south as St. Louis, is under British control and will remain so until the horse trading at Ghent restores the status quo.

*

Not to be confused with Lieutenant Richard Bullock, also of the 41st, a coincidence of nomenclature that has misled many historians.

TEN

The Last Invasion

July–November, 1814

Unable to seize either Kingston or Montreal, the Americans decide to make another drive at the Niagara peninsula. Jacob Brown, newly promoted to major-general, plans to seize Fort Erie, march down the Niagara and, with the help of the navy, capture Fort George, then move on to Burlington Heights. With the European war ended, Britain is planning to ship massive reinforcements to Canada, but these have not yet arrived. When Lieutenant-General Gordon Drummond asks Sir George Prevost for more men, he is told there are none to spare. His five thousand troops, scattered from York to Fort Erie, are not enough to contain the enemy attack

.

BEFORE FORT ERIE, UPPER CANADA, JULY 3, 1814

It is two o’clock on a black, rainy morning when Winfield Scott in the lead boat of the American invasion force, thirty-five hundred strong, leans over the bulwark to check the depth of the water with his sword. It is less than knee deep. As musket balls whiz above his

head, Scott leaps over the side and is about to shout “Follow me!” when the boat swerves in the current and he steps into a hole.

“Too deep!” gurgles Scott, as he disappears below the surface.

The warning cry prevents 150 men from drowning. The boat backs water as her crew struggles to haul the big brigadier-general, heavily encumbered by cloak, high boots, sword, and pistols, aboard. No one laughs; Scott is sensitive about his dignity. A moment later, in the shallows of a small cove near Fort Erie, he goes over the side again. His men follow. The British pickets gallop away.

Thus begins the third major invasion of the Niagara frontier, proposed less than a month before—and in the most casual fashion—by John Armstrong, the American Secretary of War.

“To give … immediate occupation to your troops, and to prevent their blood from stagnating, why not take Fort Erie?” the Secretary suggested to Major-General Jacob Brown, almost as though he were planning a weekend outing. Scott, with his sense of history, would have liked to wait a day and seize his objective on the anniversary of his country’s independence, but the impatient Brown is not to be delayed. After capturing Fort Erie, he plans to seize the strategically important bridge over the Chippawa and march downriver to Fort George, where he fully expects Commodore Chauncey to be waiting, ready to give him heavy support from his reinforced fleet.

One officer opposes Brown’s plan. Scott’s fellow brigadiergeneral, Eleazar Wheelock Ripley, believes the force is too small to make an impression upon the peninsula and that if the British dominate Lake Ontario the Americans are likely to be cut off and captured. When Brown attempts to reason with him, Ripley sullenly offers his resignation. Brown curtly tells him to follow orders, and Ripley does so—but tardily. Ripley goes down in Brown’s mental notebook as a hesitant, untrustworthy officer.

The British garrison at Fort Erie is heavily outnumbered by Ripley’s and Scott’s regulars and by more than one thousand militia volunteers and Indians under Amos Hall’s replacement, Congressman Peter B. Porter. At five it surrenders. For the Americans it has been a long, weary day; after more than twenty-four hours of

constant movement, young Jarvis Hanks, the drummer boy, cannot stay awake and finds himself dropping off to sleep on the march.

But the following day—July 4—is as glorious as its name: the rain dispersed, the sky cloudless, a haze of heat already shimmering over the grain fields and fruit orchards that border the Niagara. Through this smiling countryside, for twelve hours Winfield Scott and his brigade drive back the forward elements of Major-General Phineas Riall’s thinly extended Niagara army, the soldiers on both sides choking in the dust and sweating in the blazing sunlight.

At dusk, the British withdraw across the Chippawa bridge to the safety of their entrenched camp. Scott prudently moves back a mile behind Street’s Creek.