Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (111 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

McRee advises Brown that victory lies in the seizure of the British cannon on the brow of the hill, just below the church. As Ripley’s troops move into line, Brown turns to Colonel James Miller, a veteran of Tippecanoe and the siege of Detroit:

“Colonel Miller, will you please to form up your regiment and storm that height.”

“I’ll try, sir,” replies Miller, and this modest reply becomes in the years that follow an American rallying cry on the order of

Don’t give up the ship

and, as well, the motto of Miller’s regiment, the 21st.

Miller does more than try. Brown has dispatched Robert Nicholas’s raw 1st Regiment, newly arrived from garrison duty on the Mississippi frontier, to act as a diversion to “amuse the infantry,” as he quaintly puts it. Nicholas’s troops give way in disorder, but Miller, on their left, leads his three hundred men forward under cover of the shrubbery to the shelter of a rail fence, directly below the guns. He can see the slow matches of the British gunners glowing in the dark, only a few yards away. He whispers to his men to lean on the fence, gain their breath, aim carefully, and fire. A single volley routs the gunners and Miller’s regiment has possession of seven brass cannon. But the British line rallies, surges forward with fixed bayonets, and a hand-to-hand battle follows, the blaze of the opposing muskets crossing one another—the Americans, as is their custom, loading their muskets with one-ounce iron balls and three buckshot to add to the carnage. The guns remain in their hands.

It is ten o’clock. The moon is down. In the blackness of a hot night the armies struggle for two hours for possession of the guns with what one of Miller’s officers calls “a desperation bordering on madness.” Seldom more than twenty yards apart, the opposing lines occasionally glimpse the faces of their enemies and the buttons on their coats in the flash of the exploding muskets. Drummond, cold as ice, refuses to give an inch. Ripley’s men, moving to support Miller, can hear the British commander’s rallying cry: “Stick to them, my fine fellows!” Ripley orders his men to hold their fire until their

bayonets touch those of their opponents, so that they can use the musket flashes to take aim.

Later, the surviving participants will try to bring order out of chaos in the reports they submit, writing learnedly of disciplined flank attacks, battalions wheeling in line, withdrawals, charges, the British left, the American right, making the Battle of Lundy’s Lane sound like a parade-ground exercise. But in truth the actual contest, swirling around the shattered church on the little knoll, is pure anarchy—a confused mêlée in which friend and foe are inextricably intermingled, struggling in the darkness, clubbing one another to death with the butts of muskets, mistaking comrades for foes, stabbing at each other with bayonets, officers tumbling from horses, whole regiments shattered, troops wandering aimlessly, seeking orders.

In the blackness, a British non-commissioned officer approaches David Douglass and salutes, mistaking him for one of his own officers:

“Lieutenant-Colonel Gordon begs to have the three hundred men, who are stationed in the lane below, sent to him, as quick as possible, for he is very much pressed.”

Douglass draws him closer, pretending not to hear distinctly, and when he approaches, seizes his musket and draws it over the neck of his horse. The man is mystified:

“And what have I done, Sir? I’m no deserter. God save the King and dom the Yankees!”

In the darkness, the light company of the British 41st is almost shattered by an American ruse. Shadrach Byfield, his stomach warmed by a noggin of rum after a seven-mile dogtrot from Queenston, hears someone in a loud voice call upon his captain to form up on the left. Who is calling? From what regiment? It is too dark to tell, but the regiment’s guide insists the voice belongs to an enemy. The bugle sounds for the company to drop. A moment later it is hit by a musket volley; two corporals and a sergeant are wounded. Byfield and his fellows leap up, fire back, and charge forward, driving the Americans away.

Jacob Brown, having sent Miller up the hill to seize the British guns, moves along the Queenston road with his aides to the rear of

Lundy’s Lane and is almost captured in the dark. Only the cry of a British officer—

“There arc the Yankees!”

—saves him. Now he comes upon Major Jesup, fighting his way back to rejoin Scott’s shattered brigade. Wounded and in pain, Jesup asks for orders and is told to form on the right of the American 2nd Brigade.

Confusion!

The British reinforcements, hurried into the line in the dark, mistake friends for enemies. The Royal Scots pour a destructive fire into the Glengarry Fencibles stationed in the woods to the west of the church. The British 103rd blunders by error into the American centre and is extricated only with difficulty and heavy casualties.

Jacob Brown vaguely discerns a long line of soldiers in the dark, tries to discover who they are, rides out in front. The line appears to be advancing. An aide spurs his horse, rides forward, and in a firm voice cries out: “What regiment is that?”

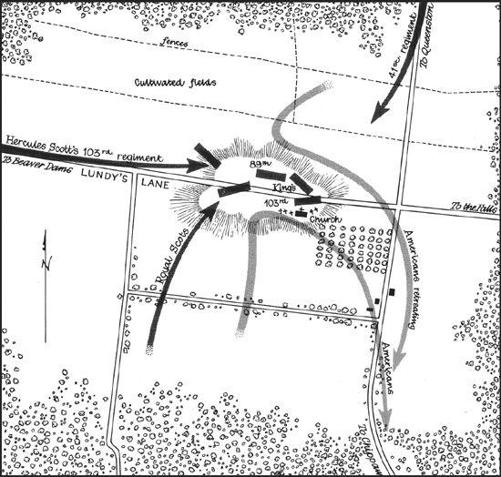

The Battle of Lundy’s Lane: Phase 2

“The Royal Scots, Sir,” comes the unexpected reply.

Brown and his suite throw themselves behind their own troops to await the attack.

Porter’s Pennsylvanians have arrived at last and are placed on the left flank of the American regulars in time to face a British charge.

“Show yourselves, men, and assist your brethren!” cries Porter.

Alexander McMullen, one of the Pennsylvania volunteers, hears a shower of musket balls pass over his head like a sweeping hail storm. Fortunately for him, the British on the knoll above are having difficulty depressing their weapons.

The battle seesaws. A pause follows each rally while each side distributes cartridges and flints or searches the bodies of the dead for ammunition. Now, as Porter’s corps ascends the hill, a stillness falls over the battlefield. The two armies face each other, neither moving. Finally, McMullen hears a British officer’s voice inquiring hoarsely if the Americans have surrendered.

No reply. Nobody moves.

A young lieutenant named Dick at last breaks the silence:

We will NEVER surrender!

On the American right some of Joseph Willcocks’s turncoat Volunteers falter and fall back, firing their muskets sporadically without orders. The British respond with a shower of lead, and the militia turns and bolts. As the Pennsylvania officers try to rally their men, Colonel Nicholas’s regulars interpose themselves between the fleeing militia and the British. Again silence, save for the murmurs of the volunteers and the groans of the dying.

Ripley, hard pressed with the British again advancing, asks Brown to order up Scott’s brigade—or what is left of it—for support. Brown hesitates. Scott’s badly mauled force is the only reserve he has. If he commits it now he will have nothing left with which to deal the enemy a finishing blow should the tide of battle turn. Nonetheless, he grants Ripley’s request.

Winfield Scott forms up his skeleton brigade in a second line behind the American right wing. He has decided upon another bold

stroke—a dash past the captured guns, piercing the British line and rolling around to take it from the rear.

“Are these troops prepared for the charge?” he asks Henry Leavenworth.

The loyal Leavenworth, the only surviving battalion commander, is given no chance to reply.

“Yes, I know, they are prepared for anything!” Scott cries and orders them into close column, shouting out an order that has almost become a cliché: “Forward and charge, my brave fellows!”

The tired troops follow their commander into the jaws of disaster. Gordon Drummond has anticipated the move and protected his flanks with the battle-seasoned 89th Regiment, whose commander, Morrison, has already left the field, grievously wounded. Kneeling in the cover of a grain field, the British regulars hold their fire, await Drummond’s order, and, at twenty paces, let loose a volley that routs Scott’s troops. The British pursue the fleeing Americans at bayonet point.

In the darkness and smoke, all is confusion. Forced down the hill and to the left of the line, Scott—who has had two horses shot from under him—again tries to lead a charge. The 89th, in hot pursuit, mistakes his force for their fellow battalion, the Royal Scots, and lets him escape.

Now Scott finds himself with the remainder of his assault party directly in front of two British regiments, the 103rd and the 104th. Fortunately for him,

they

mistake him for the British 89th.

“The 89th!” warns a British officer, just as his men are about to decimate Scott’s ranks.

“The 89th!” call out the Americans, realizing the British mistake.

Scott leads his detachment back toward his own lines, only to blunder into two more British regiments, the real Royal Scots and the 41st, who are too far forward of their own line. A bitter hand-to-hand struggle ensues, the opposing troops standing toe to toe, slashing and hacking at each other. Up come the Glengarries to support the British regulars, but they too are confused in the darkness, mistaking the Royals and 41st for American regiments. As the

two British forces grapple with one another, Scott’s men are able at long last to retire.

Scott moves to Jesup’s detached battalion on the extreme right of the American line and asks after his wound. A moment later he is prostrated by a one-ounce ball that shatters his left shoulder joint. Scott is in a bad way, for he is a mass of bruises from two falls from horseback and from the rebound of a spent cannonball that ploughed into his right side. Two men move him to the rear and place him against a tree where, on reviving, he finds he cannot raise his head from pain and loss of blood.

Brown, meanwhile, is on the far side of the field with Porter’s volunteers. A musket ball passes through his right thigh, but he remains on his horse. His aide falls mortally wounded. Now the American commander suffers a violent blow from a spent cannonball. Badly winded and bleeding, he determines to turn his command over to Scott. On learning that Scott is wounded, he passes it to Ripley.

It is past eleven o’clock and the battlefield is silent. As if by agreement, both sides cease fighting. Henry Leavenworth, in command of Scott’s brigade, counts his men, finds he has fewer than two hundred, confers with Jesup, agrees that the troops ought to return to camp. The British have quit the hill and may at any moment cut off the American withdrawal. Almost every battalion commander has been disabled; the men are exhausted and suffering from a raging thirst, for there is no water. Some have left the field. There are no reserves; Brown has committed every man.

For Alexander McMullen of the Pennsylvania militia, these will be, in retrospect, the most trying moments of his life. Sweating heavily during the attack up the hill, he had opened his vest and shirt. Now he shivers in the night air, and not only from the midnight chill; the prospect of imminent death disturbs him more. He hopes against hope that he will not have to struggle one more time up that terrible slope, now strewn with corpses.

It is clear to all, including Brown, that the army must retire. Major Hindman of the artillery encounters the wounded general, who orders him to collect the guns and march to camp.

But how are the captured guns to be removed? Most of the horses are dead, the caissons blown up, the guns unlimbered, the men exhausted, the drag ropes non-existent. Hindman decides to try to bring away one of the brass twenty-four-pounders, assigns a junior officer, Lieutenant Fontaine, to get it ready, then goes in search of horses. But Drummond, bleeding from a wound in the neck, is already forming his battle-weary British for a final assault. Once more his battered battalions press up the slope and retrieve the guns just as Hindman returns with horses and wagons. Fontaine dashes through the ranks on horseback; the rest of his party is captured.

The British are too exhausted to harass the retreating Americans. Most of the men have marched eighteen miles on this hot July day, some twenty-one. They throw themselves down among the corpses and in their sleep are scarcely distinguishable from the dead. Ripley’s troops straggle back to the camp at Chippawa, plunge into the river to slake their thirst, then fall into their tents.

It has been the bloodiest battle of the war, the casualties almost equal on both sides. The British count some 880 officers and men killed, wounded, or captured, the Americans almost as many (although some will charge that Brown has purposely underestimated his returns). William Hamilton Merritt, leader of the Provincial Dragoons and now an American captive, is one who will not fight again.

Both sides claim victory. Drummond reports that the day has “been crowned with complete success by the defeat of the enemy and his retreat to the position of Chippawa.…”

Brown declares that “the enemy … were driven from every position they attempted to hold … notwithstanding his immense superiority both in numbers and position, he was completely defeated.…”

Nothing will ever shake Winfield Scott’s conviction that the Americans won a brilliant victory, for which he was largely responsible. Certainly his men bore the brunt of the fighting. Of a total of 860 American casualties, Scott’s brigade suffered 516. Scott is contemptuous of Brown; he considers him a flawed commander and is stung by Brown’s report of the action, which, he feels, does not give him sufficient praise. It is “lame and imperfect, unjust and incomplete.”