Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (92 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

The Secretary’s instincts are often sound but his execution indecisive. It has always been obvious to him that the key to victory in Canada lies in the capture of Kingston, but in his orders to Wilkinson he has covered himself carefully to escape blame for future defeat. Kingston, he declares, “represents the

first

and

great

object of the campaign.” Then he equivocates, explaining that it can be attacked in two ways: directly by assault, or indirectly by sweeping down the St. Lawrence to Montreal, thus cutting its supply line. The Secretary is an expert at making the obvious appear significant. Whether Wilkinson chooses to attack Kingston or Montreal, Armstrong can always point out that he suggested an alternative course.

Now here he is at Sackets Harbor, a handsome figure, about to turn fifty-six, with a proud, unlined face, regular features, and hooded eyes, aristocratic by nature, pugnacious by temperament—“eminently

pugnacious,” in Martin Van Buren’s phrase—ambitious, caustic, but like Wilkinson outwardly convivial.

They make a strange pair, the general and the politician who hold the fate of Canada in their hands. Friends once, then enemies, they are friends again, or seem to be. While serving together in 1792 they had such a falling out that Armstrong, charged by Wilkinson with fraud, left the army in disgust. That has been patched up; Wilkinson is the Secretary’s choice as commander. But it is an uneasy alliance. To the ailing general, Armstrong’s presence is unsettling. He feels his command undermined, his prestige lessened, for the Secretary has been bustling about, making free with advice that, not surprisingly, is accepted as command.

Wilkinson is so sick that he has almost ceased to care. Weakened by a series of paroxysms, he tells Armstrong he is incapable of command and wants to retire. The Secretary insists he is indispensable, assures him that he will soon recover, and remarks to one of his staff, “I would feed the old man with pap sooner than leave him behind.” It is indicative of their relationship that the “old man” is scarcely a year older than Armstrong.

Indecision marks their deliberations. Neither can make up his mind whether the main attack should be on Kingston or on Montreal. Whichever objective one favours, the other opposes. Almost at their first encounter, Wilkinson vigorously espouses Montreal. Armstrong differs but covers himself with a cloud of ambiguities. A fortnight later both men trade positions, Armstrong arguing that circumstances have changed. But when Wilkinson asks for a direct order in writing, the Secretary declines, referring him to his earlier letter about “direct” and “indirect” attacks.

It is becoming obvious that neither man expects an attack on Kingston or Montreal to succeed; in this documentary confrontation they are carefully protecting themselves from future charges of failure.

Armstrong, the would-be commander, is the author of a pompous little book entitled

Hints to Young Generals

. “The art of war,” he has written, “rests on two [principles]—concentration of force and

celerity of movement.” It cannot be said that the army is moving with celerity at Sackets Harbor. Nineteen days are spent loading the boats with provisions, a task the contractor’s agent believes could be done in five. The boats are encumbered with hospital stores instead of guns and powder, and these stores are scattered throughout the flotilla without any plan.

This is especially significant because the squadron, when it does move, will resemble a floating hospital—a term specifically used by William Ross, the camp surgeon. In September, some seven hundred men and officers lie ill; that number will double within two months.

The chief causes are bad food—which, in Dr. Ross’s words, has “destroyed more soldiers than have fallen by the sword of the enemy”—and wretched sanitation. The meat is rotten, the whiskey adulterated, the flour so bad that “it would kill the best horse in Sacket’s Harbor.” The greatest offender is the bread, which when examined is found to contain bits of soap, lime, and, worst of all, human excrement. The bakers take their water from a stagnant corner of the lake, no more than three feet from the shore. Into the lake pours all the effluent from a cluster of latrines a few yards away. Naked men knead the dough. Nearby is a cemetery housing two hundred corpses, together with the contents of a box of amputated limbs marked “British arms and legs,” buried in no more than a foot of sandy soil. But although the troops are weak from dysentery and the leading officers have been warned of the problem, nothing is done. His subordinates are convinced that Wilkinson is too ill to be told and too weak (from the same condition) to act upon the information if he were.

The word from Major-General Wade Hampton, meanwhile, is not such as to inspire confidence. Hampton’s army of four thousand regulars and fifteen hundred militia at Lake Champlain has been ordered to support Wilkinson’s attack. The difficulty is that Hampton hates Wilkinson so much that he will not take orders from him. Indeed, he has secured the ambiguous agreement of the Secretary of War that his will be a separate command. Unfortunately,

Armstrong has also assured Wilkinson that Hampton really will act under his orders. The result is that although Wilkinson has sent directions to Hampton, two hundred miles away, Hampton has not deigned to answer. In the end all communication between the two generals has to be passed through Armstrong.

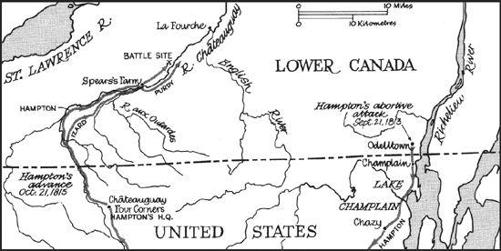

Hampton’s army has reached Châteauguay Four Corners, just south of the border, after a dismal attempt to follow Armstrong’s instructions to create a diversion near the Canadian village of Odell-town. The attack failed on September 21 because of unseasonably hot weather. Horses and men were so desperate with thirst that the entire force had to withdraw and march seventy miles to its present situation.

Now Hampton too seems to be covering himself against failure. He reports that his troops are raw and that illness is increasing daily. “All I can say is it shall have all the capacity I can give it,” he writes, lamely.

Armstrong tells him to hold fast at Four Corners “to keep up the enemy’s doubts, with regard to the real point of your attack”—a necessary order, since Armstrong himself does not know where the real point of attack will be. Finally, on October 16 he instructs Hampton to move down the Châteauguay River and cross the border, either as a feint to support the thrust against Kingston or to await the main body of Wilkinson’s army on its movement down the St. Lawrence to Montreal.

Wade Hampton’s Movements, September—October, 1813

At this point, more than half of Wilkinson’s combined forces have yet to reach the rendezvous point at Grenadier Island. A winter storm has been raging for a week, lashing the waters of the lake with rain, snow, and hail. Those few boats that do set off are destroyed or forced back to harbour. Do Wilkinson and Armstrong really believe they can seize Canada before winter?

By October 19, when the weather abates and the main body sets off, the ground is thick with snow. And still no one can be sure whether Kingston or Montreal will be the main point of the attack.

CHÂTEAUGUAY FOUR CORNERS, NEW YORK STATE, OCTOBER 21, 1813

For the past eighteen days, two Canadian farmers, Jacob Manning and his brother, David, have been held captive by the Americans in a log stable on Benjamin Roberts’s farm, where Wade Hampton’s army is camped. Suddenly word comes that the Major-General himself wishes to speak to them.

The Mannings are spies—part of a small group recruited by the British from the settlers of Hemmingford and Hinchinbrook townships just north of a border that was, until war broke out, little more than an imaginary line. This is smugglers’ country. The settlers know one another intimately and, no matter what their allegiance, still continue an illicit trade—the Americans sneaking barrels of potash into Canada for sale in Montreal, the Canadians slipping over the line, pulling hand sleds loaded with ten-gallon kegs of hard-to-get whiskey. So much beef is shipped into Canada for the British Army that herds of cattle have left discernible tracks in the woods along the Hinchinbrook frontier.

For some time the Mannings have been supplying the British with reports of American troop movements. But on the night of October 2, an American patrol descended on their farmhouse near Franklin and surprised the two brothers asleep. Since that night they have been held under suspicion.

They are brought under guard to Hampton’s headquarters at

Smith’s Tavern, where the Major-General himself receives them. A large and imposing Southerner in his sixtieth year, Hampton is known for his impatience, his hauteur, and his hasty temper. Subordinates and superiors find him difficult to get along with, perhaps because he is a self-made man with all the stubbornness, pride, and ego that this connotes. An uneducated farm boy—orphaned early in life by a Cherokee raid that wiped out most of his family, including his parents—he is well on his way to becoming the wealthiest planter in the United States. He has a hunger for land—greed might be a better word—and has made a fortune in speculation, much of it bordering on the shady. In South Carolina he is the proprietor of vast plantations that support thousands of slaves, some of whom wait upon him here at Four Corners, to the raised eyebrows of the northern settlers. He is both a politician and a soldier, with a good Revolutionary record and a background that includes a stint in Congress and several other public offices. Now, entering his seventh decade, he seems to have lost his drive—the panache that made him one of General Thomas Sumter’s most daring officers. He is not popular. Morgan Lewis has flatly refused to serve under him; several other officers at Fort Niagara have sworn they would resign their commissions if Hampton were placed in charge of that frontier.

His orders are to cross the border and march down the Châteauguay to the St. Lawrence. If Wilkinson attacks Kingston, this move will confuse the British. Otherwise, his army will join Wilkinson’s on its sweep to Montreal.

Hampton is as much in the dark regarding British and Canadian strength and intentions as the British are of American strength and strategy. That is why he has called for the Manning brothers. He wants David Manning to take his best black charger, gallop to Montreal, and bring him back an estimate of the British defence force there. There will be no danger, the General assures Manning; no one will suspect him, and if he does his job well there will be a handsome reward.

Manning refuses.

“Are you not an American?” Hampton demands.

“Yes,” says Manning. “I was born on the American side and I have many relations, but I am true to the British flag.”

He is a Loyalist—a Tory who refused to fight against the British during the Revolution and was forced to move north of the border.

Hampton’s famous temper flares. He roughly tells the Manning brothers that they are in his power and will be sent to the military prison at Greenbush if they do not toe the line.

The two backwoodsmen are not cowed. They reply, cheekily, that anything will be better than confinement in a filthy stable; perhaps they will be treated like human beings at Greenbush.

Hampton tries a different tack, asks if there is a fort at Montreal. When they tell him that none exists, he refuses to believe it. He takes the two men to the tavern window overlooking the Roberts farm and proudly points out the size of his army.

Spread out before them, the brothers see an imposing spectacle: thousands of men striking their tents, cavalry cantering about, the infantry drilling in platoons. Clearly, Hampton is about to move across the Canadian border.

The General proudly asks how far the Mannings think a force of that size can go. Again, Jacob Manning cannot resist a cheeky answer.

“If it has good luck it may get to Halifax,” he says—for Halifax is the depot to which prisoners of war are sent.

Angered, Hampton orders his officer of the guard, a local militiaman named Hollenbeck, to take the brothers back to the stable and keep them there for three days to prevent word of his advance reaching the British.

But Hollenbeck is an old friend and neighbour.

“Do you want anything to eat?” he asks.

“No,” says Jacob.

“Well, then, put for home,” says Hollenbeck. Off go the brothers with news of Hampton’s advance.

Theirs is not the only intelligence to reach the British. Hampton’s forward troops under Brigadier-General George Izard are already across the border. At four o’clock they reach Spears’s farm at the junction of the Châteauguay and Outarde rivers and rout a small

Canadian picket, which sounds the alarm. For weeks the border country has been in a state of tension, not knowing exactly where the American attack on Lower Canada will come. Now it is clear that Hampton’s main force will advance along the cart track that borders the Châteauguay. His object is the St. Lawrence River and, surely, Montreal.

In the coming battle the defence of Canada will fall almost entirely to the French-Canadian militia. More than three hundred are already moving up the river road to a rendezvous point in the hardwood forest not far from the future settlement of Allan’s Corners—the Sedentary Militia from Beauharnois in homespun blouses and blue toques, and two flank companies of the 5th Battalion of Select Embodied Militia in green coats with red facings. This is the notorious Devil’s Own battalion recruited from the slums of Montreal and Quebec, and so called because of its reputation for thievery and disorder.