Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (96 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

This confusion and delay does not sit well with John Boyd on shore. Since early morning, he has been subjected to a variety of conflicting orders. At noon, a violent storm further reduces the morale of the troops who have now been under arms for nearly forty-eight hours. Boyd rides impatiently to the river bank where he finally receives a pencilled order to put his troops in motion in twenty minutes as soon as the guns can be put ashore. It is the last order he receives from Wilkinson.

Boyd will command the American forces in the battle to follow. A one-time soldier of fortune who for twenty years sold his services to a variety of Indian princes, including the Nizam of Hyderabad and the Peshwa of Poona, he exchanged his turban and lance in 1808 for a colonel’s eagle in the U.S. 4th Infantry. Commissioned brigadiergeneral at the opening of the war, he does not enjoy the esteem of his peers. Brown cannot stand him. Scott considers him imbecilic. Lewis, in a vicious indictment, describes him as “a combination of ignorance, vanity, and petulance, with nothing to recommend him but that species of bravery in the field which is vaporing, boisterous, stifling reflection, blinding observation.” Not the best man to put up against British regulars.

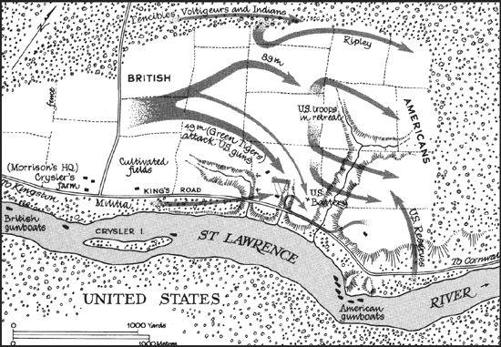

Boyd’s first move is to send Lieutenant-Colonel Eleazar Ripley’s regiment across the muddy fields and over a boggy creek bed to probe Morrison’s forward skirmishers in the woods on the British left. Ripley advances half a mile when a line of Voltigeurs suddenly rises from concealment and delivers two volleys at his men who, disregarding the cries of their officers, leap behind stumps and open individual fire until, their ammunition exhausted, they run back out of range. Ripley retires with them but soon returns to the attack with reinforcements and drives the Voltigeurs back.

John Sewell, the British lieutenant whose breakfast was so rudely interrupted, is standing with his fellow Green Tigers in the thin line formed by the two British regiments when he sees the grey-clad Voltigeurs burst from the woods on his left, pursued by the

Americans. The situation is critical. If Ripley’s men can get around the 89th, which holds the left flank, and attack the British from the rear, the battle is as good as lost.

The Battle of Crysler’s Farm: Phase 2

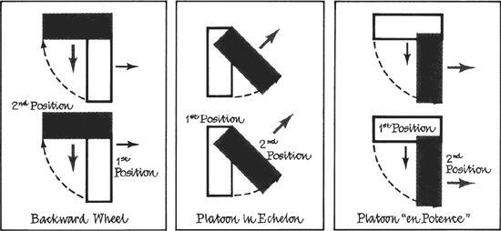

Morrison now executes the first of a series of parade-ground manoeuvres, wheeling the entire 89th Regiment from its position in line, facing east, to face north—

en potence

, to use the military term. Emerging from the woods, the Americans encounter a solid line of scarlet-coated men firing muskets in unison. They break and run. The contrast between the fire of the opposing forces is so distinct that the women and children hiding in Captain John Crysler’s cellar can easily tell the American guns from the British: the former make an irregular pop-pop-pop; the latter, at regular intervals, resound “like a tremendous roll of thunder.”

Thwarted in his attempt to turn the British left, Boyd now advances his three main brigades across the open wheatfields in an attempt to seize the British right. Leonard Covington, the forty-five-year-old Marylander who commands the 3rd Brigade—a veteran of Anthony Wayne’s frontier army—is fooled by the grey coats of the 49th directly in front of him.

British Infantry Tactics at Crysler’s Farm

“Come, lads, let me see how you will deal with these militia men,” he shouts.

But the disguised Tigers are already executing another familiar drill—moving into echelon, a line of staggered platoons, which, supported by six-pounders, fire rolling volleys against the advancing Americans.

The action has now become general, a confused mêlée of struggling men, half obscured by dirty grey smoke, weaving forward and backward, floundering in the ankle-deep mud, splashing and dying in the stream beds, tumbling into gullies, clawing their way out of ravines until no one, when it is over, is able to produce a coherent account of exactly what went on.

Certain key moments emerge from the fog of battle. In one of several assaults on the British line, Brigadier-General Covington falls mortally wounded while attempting to seize the British cannon. His second-in-command is also killed. This critical loss, followed by the loss of two more senior officers, causes confusion in the American 3rd Brigade.

At about the same time, the American artillery, hauled from the boats and late getting into position, begins to harass the advancing British. Morrison orders Plenderleath to attack the guns with the heavy troops of the 49th, for unless they can be silenced the grape-shot will cut the outnumbered British to pieces.

Plenderleath’s Green Tigers are about 120 yards from the enemy. Off they go through the deeply ploughed field, trampling the grain, kicking up the mud, tearing down two snake fences that bar their path, unable to fire back as they struggle with the heavy logs under a galling hail of shot from the American six-pounders.

John Sewell, advancing with his company into the hail of grape, sees his captain killed, takes over, and suddenly spies a squadron of American dragoons galloping down the King’s road on his right. He realizes the danger: if the horsemen get around the flank, they can wheel about and charge the British from the rear. Fortunately, another drill book manoeuvre exists to meet this threat. Captain Ellis on the right wing executes it under Plenderleath’s command, wheeling his men backward to the left to face the line of cavalry. Sewell notes that the entire movement, which the Americans believe to be a retreat, is carried out with all the coolness of a review as the commands ring out over the crash of grape and canister:

Halt … Front … Pivot … Cover … Left wheel into line … Fire by platoons from the centre to the flank

. The effect is shattering as the wounded American horses, snorting and neighing, flounder about, their saddles empty.

At the same time, a light company of the 89th stationed well ahead of the main ravine charges the American artillery, captures a six-pounder, and kills its crew. By now the whole American line is giving way, and the retreat is saved from becoming a rout only by the presence of American reserves.

Wilkinson, who has spent the day in his bunk lamenting his ill fortune at not being with his men, tries to prevent a pell-mell rush to the boats, exclaiming that the British will say that the Americans were running away and claim a victory. He sends a message to Boyd, asking if he can maintain himself on the bank that night to preserve some vestige of American honour. Boyd’s answer is a curt

No:

the men are exhausted and famished; they need a complete night of rest.

Boyd now busies himself with the mandatory report of the day’s action, which is, as always in defeat, a masterpiece of dissembling. He cannot actually claim victory but comes as close to it as he can, larding his account with a litany of alibis:

… though the result of this action were not so brilliant and decisive as I could have wished, and the first stages of it seemed to promise, yet when it is recollected that the troops had been long exposed to hard privations and fatigues, the inclement storms from which they could have no shelter; that the enemy were superior to us in numbers [sic], and greatly superior in position, and supported by 7 or 8 heavy gunboats; that the action being unexpected, was necessarily commenced without much concert; that we were, by unavoidable circumstances long deprived of our artillery; and that the action was warmly and obstinately contested for more than three hours, during which there were but a few short cessations of musketry and cannon; when all these circumstances are recollected, perhaps this day may be thought to have added some reputation to the American arms. And if, on this occasion, you shall believe me to have done my duty, and accomplished any of your purposes, I shall be satisfied.…

Wilkinson, in his report to the Secretary of War, does not shillyshally. He inflates the British strength from 800 to 2,170, bumps up the British casualties from 170 to 500, and declares that “although the imperious obligations of duty did not allow me sufficient time to rout the enemy, they were beaten.…”

But it is Wilkinson who is beaten. “Emaciated almost to a skeleton, unable to sit my horse, or to move ten paces without assistance,” he seeks an excuse to give up the grand campaign and receives it the morning after the battle in the form of a letter from General Hampton.

The two armies were supposed to meet just below the Long Sault, at St. Regis opposite Cornwall. Wilkinson’s flotilla makes the passage, but Hampton is not there and never will be. It is impossible, he reports, to transport enough supplies to the St. Lawrence to feed the army; his arrival would only weaken the existing force; the roads are impracticable for wheeled transport; his troops are raw, sick, exhausted, dispirited. He intends to go back to Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain and strain every effort to throw himself on the

enemy’s flank along the old Champlain-Richelieu invasion route. This is mere posturing. He intends to do nothing.

Now Wilkinson has his scapegoat. Montreal, just three days downriver, is virtually defenceless. Hampton’s apparent feint at Châteauguay and his sudden withdrawal has convinced Prevost to withdraw the bulk of the British troops to Kingston. Wilkinson still has some seven thousand soldiers. But neither he nor his generals have the will to continue. A hastily summoned council of war agrees to abandon the enterprise.

Wilkinson goes to some effort to make it clear that the defeat of the grand plan is entirely Hampton’s fault. In his General Order on November 13 he announces that he is “compelled to retire by the extraordinary unexampled, and apparently unwarrantable conduct of Major General Hampton.”

To Armstrong he writes that, with Hampton’s help, he would have taken Montreal in eight or ten days. Now all his hopes are blasted: “I disclaim the shadow of blame because I have done my duty.… To General Hampton’s outrage of every principle of subordination and discipline may be ascribed the failure of the expedition.…”

The army drifts eighteen miles down the St. Lawrence to Salmon Creek and moves up that tributary to the American hamlet of French Mills, soon to be known as Fort Covington in honour of the dead general. Here, in a dreary wilderness of pine and hemlock, with little shelter and hard rations, it passes a dreadful winter. Sickness, desertions, and venality do more damage than any British force. Clothing is hard to come by. Little Jarvis Hanks, the drummer boy, has no pantaloons and is forced to tailor himself a pair out of one of his two precious blankets. Driven to subsist on contaminated bread, the men sicken by the hundreds and die by the score. So many men are mortally stricken that funeral dirges are banned from the camp for reasons of morale. By the end of the year almost eighteen hundred are ill. Food is so scarce the sick must subsist on oatmeal, originally ordered for poultices. All of the efficient officers have gone on furlough or are themselves ill with pneumonia, diarrhea, dysentery, typhoid, or atrophy of the limbs, a kind of dry rot. The remainder,

ex-ward politicians mostly, fatten their pocketbooks by selling army rations to British and Americans alike, and drawing dead men’s pay.

The defeat on the St. Lawrence wrecks the careers of the men who bungled the grand attack. Wilkinson, convalescing in a comfortable home at Malone, New York, and bitterly blaming everybody but himself for the debacle, must know that his days are numbered. Hampton will shortly resign, to the relief of all. Lewis and Boyd have each taken a leave of absence and will not be heard of again.

Jacob Brown, promoted to major-general, and George Izard, Hampton’s efficient second-in-command, represent the new army. When the force at French Mills breaks up the following February, Brown takes two thousand men to Sackets Harbor to continue the struggle for the Niagara frontier while Izard marches the rest to Plattsburgh.

Along the St. Lawrence, the settlers begin to rearrange the fragments of their lives. The north shore has been heavily plundered of cattle, grain, and winter forage. Fences have been ripped apart to build fires—the sky so illuminated it sometimes seemed as if the entire countryside was ablaze. Cellars, barns, and stables have been looted. Stragglers, pretending to search for arms, rummaged through houses, broke open trunks, stole everything from ladies’ petticoats to men’s pantaloons. Fancy china, silver plate, jewellery, books—all went to the plunderers in spite of Wilkinson’s proclamation that private property would be respected.