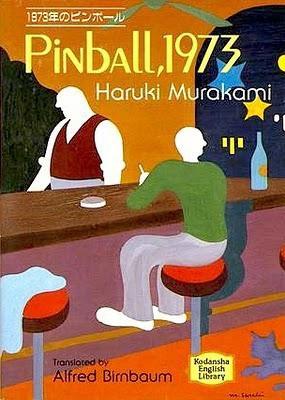

Pinball, 1973

Authors: Haruki Murakami

Pinball, 1973

By Murakami Haruki

Translated by Alfred Birnbaum

I used to love listening to stories about faraway places. It was almost pathological.

There was a time, a good ten years ago now, when I went around latching onto one person after another, asking them to tell me about the places where they were born and grew up. Times were short of people willing to lend a sympathetic ear, it seemed, so anyone and everyone opened up to me, obligingly and emphatically telling all. People I didn’t even know somehow got word of me and sought me out.

It was as if they were tossing rocks down a dry well: they’d spill all kinds of different stories my way, and when they’d finished, they’d go home pretty much satisfied. Some would talk contentedly; some would work up quite an anger getting it out. Some would put things well, but just as often others would come along with stories I couldn’t make head nor tail of from beginning to end. There were boring stories, pathetic tear-jerkers, jumbles of half-nonsense. Even so, I’d hold out as long as I could and give a serious listen.

Everyone had something they were dying to tell somebody or shout to the whole world – who knows why? I always felt as if I’d been handed a cardboard box crammed full of monkeys. I’d take the monkeys out of the box one at a time, carefully brush off the dust, give them a pat on the bottom, and send them scurrying off into the fields. I never knew where they went from there. They probably ended their days nibbling acorns somewhere. But that, after all, was their fate.

That was the thing about it. There was so little return on all the effort involved. Thinking back on it now, I’ll bet if there had been a World’s Most Earnest Listener contest that year, I’d have won hands down. And I’d probably have won a box of kitchen matches.

Among the people who talked to me were a guy from Saturn and another from Venus, one each. Their stories really got to me. First, the one about Saturn.

“Out there, it’s . . . awful cold,” he groaned. “Just thinking about it, g-gives me the willies.”

He belonged to a political group that had staged a take-over of Building 9 in the university. Their motto was “Action Determines Ideology – Not the Reverse!” No one would tell him what determined action. No matter, Building 9 had a water cooler, a telephone, and boiler facilities; and upstairs they had a nice little music lounge complete with Altec A-5 speakers and a collection of two thousand records. It was paradise (compared to, say, Building 8, which smelled like a racetrack restroom). Every morning they’d shave themselves neat and clean with all the hot water they wanted, in the afternoon they’d make as many long-distance calls as they felt like, and when the sun went down they’d all get together and listen to records. By the end of autumn, every member had become a classical music fanatic.

Then one beautifully clear November afternoon, riot police forced their way into Building 9 while Vivaldi’s L’Estro Armonico was blaring away full blast. I don’t know how true all this is, but it remains one of the more heartwarming stories of 1969.

When I snuck past their “barricade” of stacked-up benches, Haydn’s Piano Sonata in G Minor was playing softly. The atmosphere was as homey and inviting as a path along a bluff blooming with sansanquas bushes leading toward a girlfriend’s house. The guy from Saturn offered me the best chair in the place, and poured lukewarm beer into beakers lifted from the science building.

“On top of that, the gravity is tremendous,” he went on about Saturn. “There’ve been chumps who broke their instep spitting out a wad of gum. A r-real hell!”

“Well, I guess so,” I prompted after a couple of seconds. By this time, I had command of nearly three hundred or so different small-talk phrases to throw in during awkward pauses.

“The sun’s so small, too. J-just one of those things. Take me - as soon as I get out of school I’m going back to Saturn. And I’ll start a gr-great nation. A r-rev-revolution!”

In any case, suffice it to say I enjoyed hearing about faraway places. I had stocked up a whole store of these places, like a bear getting ready for hibernation. I’d close my eyes, and streets would materialize, rows of houses take shape. I could hear people’s voices, feel the gentle, steady rhythm of their lives, those people so distant, whom I’d probably never know.

* * *

Naoko often spoke to me about these things. And I remember her every word.

“I really don’t know how to put it.” Naoko forced a smile, sitting in the sunlit university lounge, elbow on the table and cheek propped up on her palm. I waited patiently for her to continue. As always, she took her time, searching for just the right words.

We sat, red plastic tabletop between us on which a paper cup spilled over with cigarette butts. A high window let in a shaft of sunlight straight out of a Rubens painting, splitting the table down the middle into light and dark. My right hand rested on the table in light, the left in shadow.

The spring of 1969, you see, we were in our early twenties. And what with all the freshmen sporting brand-new shoes, carrying brand-new course descriptions, heads packed with brand-new brains, there was hardly room to walk in the lounge. On both sides of us, freshmen were perpetually bumping into one another, exchanging insults or greetings.

“I tell you, the town is really nothing to speak of,” she resumed. “There’s a straight stretch of track, and a station. A pitiful little station that the trainmen could easily miss on a rainy day.”

I nodded. Then for a full thirty seconds the two of us gazed absently at the cigarette smoke curling up through the beam of light.

“A dog’ll be walking from one end of the platform to the other. You know the kind of station.”

I nodded.

“Right out in front of the station there’s a bus stop and a circular drive so cars can pick up and drop off passengers. And some shops . . . real sleepy little shops. Straight ahead, you run into a park. A park with a slide and three swings.”

“And a sandbox?”

“A sandbox?” She thought for a moment, then nodded in confirmation. “It’s got one.

Once more we fell silent. I carefully put out the stub of my cigarette in the paper cup.

“A terribly boring town. I can’t imagine what possible purpose there could have been for making such a dull place.”

“God works in wondrous ways,” I quipped.

Naoko shook her head and smiled to herself. It was a sort of straight-A coed smile, but it lingered in my mind an oddly long time. Long after she’d gone, her smile remained, like the grin of the Cheshire Cat in Alice in Wonderland. And it occurred to me how much I wanted to see that dog pacing the length of the station platform.

* * *

Four years later, in May of 1973, I visited the station alone. Just to see that dog. I shaved for the occasion, put on a tie for the first time in six months, and brought out my Cordovan shoes.

* * *

Stepping down from the sorry two-car local train that seemed ready to rust up any minute, the very first thing to hit me was the familiar smell of open grassy spaces. The smell of picnics way back when. Nostalgic things, all blown my way on the May breeze. I cocked my head and strained to listen, and I could make out the twittering of sparrows.

Letting out a long yawn, I sat down on a station bench and dejectedly smoked a cigarette. That invigorating feeling I’d left the apartment with in the morning had utterly vanished. Nothing but more of the same, over and over. Or so it seemed. An endless deja vu, growing worse at every turn.

There had been a time when friends and I used to fall asleep sprawled out any which way on the floor together. At dawn, someone would invariably step on my head. Then it would be “Oops, sorry,” followed by that same someone taking a leak. More of the same, over and over again.

I loosened my tie and, cigarette dangling from the corner of my mouth, I scraped the soles of the not-quite-broken-in shoes on the platform. To lessen the pain in my feet. Not that the pain was all that bad, but it gave me the uneasy feeling that my body was somehow broken into bits and pieces.

No sign of any dog.

* * *

An uneasy feeling ...

This uneasiness comes over me from time to time, and I feel as if I’ve somehow been pieced together from two different puzzles. Whatever it is, at times like these I toss down a whiskey and hit the sack. And when I get up in the morning, things are even worse. More of the same, one more time around.

One time when I woke up, I found myself flanked by twin girls. Now things like this had happened to me many times before, but I had to admit a twin to each side was a first. The both of them sleeping away, noses nestled snugly into my shoulders. It was a bright, clear Sunday morning.

Finally, they both woke up – almost simultaneously – and proceeded to worm into the shirts and jeans they’d tossed under the bed. Without so much as a word, they went into the kitchen, made toast and coffee, got butter from the fridge, and laid it all out on the table. They knew what they were doing. Outside the window, birds, which I couldn’t identify either, perched on the chainlink fence of the golf course and chattered away rapid fire.

“Your names?” I asked them. I had a nasty hangover.

“They’re not much as names,” said the one seated on the right.

“Really, nothing special as names go,” said the one on the left. “You know how it is.”

“Yeah, I know,” I said.

So we sat facing each other across the table, munching toast and drinking coffee. The

coffee was good.

“Does it bother you, us not having names?” one of them asked.

“Hmm ... what d’you think?”

The two of them gave it some thought.

“Well, if you simply must have names for us, choose something that seems to fit,” proposed the other.

“Call us whatever you like.”

The girls always took turns speaking. It was like an FM stereo check, and made my head even worse.

“For instance?” I asked.

“Left and Right,” said one.

“Vertical and Horizontal,” said the other.

“Up and Down.”

“Front and Back.”

“East and West.”

“Entrance and Exit,” I managed to get in, not to be outdone. The two of them looked at each other and laughed contentedly.

* * *

Where there’s an entrance, there’s got to be an exit. Most things work that way. Public mailboxes, vacuum cleaners, zoos, plastic condiment squeeze bottles. Of course, there are things that don’t. For example, mousetraps.

* * *

I once set a mousetrap under my apartment sink. I used peppermint gum for bait. After scouring the entire apartment, that was the only thing approaching food I could find. I found it in the pocket of my winter coat, along with a movie ticket stub.

By the third morning, a tiny mouse had flirted with fate. Still very young, the mouse was the color of those cashmere sweaters you see piled up in London duty-free shops. It was maybe fifteen or sixteen in human years. A tender age. A bitten-off piece of gum lay under its paws.

I had no idea what to do with the thing now that I’d caught it. Hind leg still pinned under the spring wire, the mouse died on the fourth morning. Seeing it lying there taught me a lesson. Everything needs an entrance and exit. That’s about the size of it.

* * *

Skirting the hills, the tracks ran so straight they seemed ruled. Far ahead you could see woods, like little wads of dull green paper. The rails glinted in the sun, merging into the green distance. No matter how far you went, the same scenery would go on forever. A depressing thought if there ever was one. Give me a subway any day.

I finished my cigarette, then stretched a bit, looking up at the sky. It had been a long time since I’d really looked at the sky. Or rather, it had been a long time since I’d tried to take a good look at anything.

Not a cloud in the sky. Moreover, the whole of it was veiled in that languid opaqueness unique to spring. From above, the blue was making a noble effort to penetrate that intangible veil, as sunlight silently sifted down like fine dust from the atmosphere, and unnoticed by anyone, seemed to form a layer over the ground.

Light was swaying in the warm breeze. The air flowed as easily as a flock of birds flitting among the trees, grouping to take flight. It glided down the gentle green slope alongside the tracks, crossed over, and slipped through the woods, hardly stirring a single leaf. The call of a cuckoo rang out straight across the softly luminous scene, the echo disappearing over the ridge. A succession of hills rose and fell, like sleepy giant cats curled in the pooled sunlight of time.

* * *

The pain in my foot grew still worse.

* * *

So let me tell you something about this well.

Naoko had moved to the area when she was twelve. 1961. The year Ricky Nelson sang “Hello Mary Lou.” It was a peaceful green valley at the time, not a single thing to claim your attention. A handful of farmhouses with a few fields, a stream full of crayfish, a one-track local railroad, barely a yawn of a train station, that was it. Most farmhouses had persimmon trees planted in the yard, and weather-beaten old barns standing to one side – or rather, tottering and ready to fall apart. And there were those cheap tin signs advertising tissue paper or soap nailed on barn walls that faced the tracks. The place really was like that. Not even a dog anywhere, Naoko had said.