Pirates of Somalia (32 page)

Read Pirates of Somalia Online

Authors: Jay Bahadur

Tags: #Travel, #Africa, #North, #History, #Military, #Naval, #Political Science, #Security (National & International)

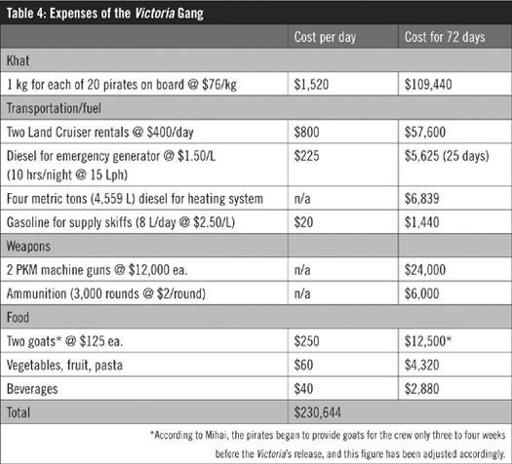

The

Victoria

was held captive from May 5 until July 18—a total of seventy-five days—of which seventy-two were spent anchored at Eyl. Assuming an average of twenty pirates on board at a given time (the “company” was not responsible for the expenditures of those on leave), the expense sheet for Computer’s operation might have totalled $230,000, as in

Table 4

. Even allowing for additional discretionary expenses of $50,000 on top of this already liberal estimate, we still fall almost halfway short of Hersi’s $500,000 figure. One explanation is that Hersi’s estimate was simply a baseless guess. But his frequent repetition of the figure suggests otherwise; perhaps $500,000 was the “official figure” bandied about in casual conversation by members of the gang.

Recalling that operating expenses were subtracted directly from Computer’s 50 per cent share of the ransom, is it possible that the boss was exaggerating his contribution in order to justify his lion’s share? Only Computer and the group’s accountant are likely to have had an accurate knowledge of its financial structure. In light of the average pirate’s lack of mathematical skills, a budget inflation of 100 per cent would hardly be too big an accounting glitch to put over on the group’s lower-ranked members.

* * *

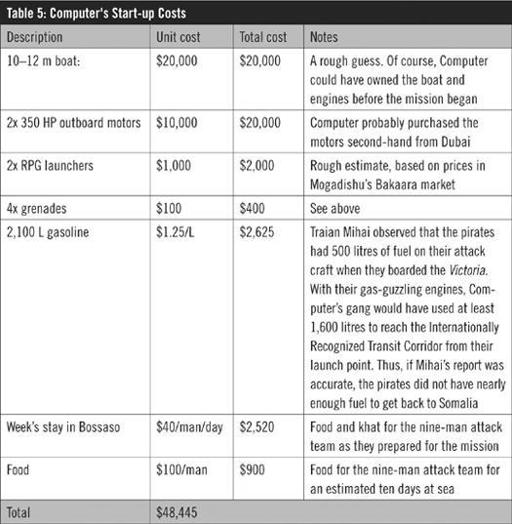

Computer had good reason to conceal the lucrative nature of his own payout. The necessary start-up capital—which went towards the purchase of a ten-to-twelve-metre boat, two outboard motors, weapons, food, and fuel—could not have exceeded $50,000 (see

Table 5

).

Of course, it is entirely possible that Computer already owned the boat and outboard motors, in which case his start-up costs would have been considerably discounted. But even if Computer’s initial contribution was in fact as high as $48,500 and his operating expenses were $230,000, he would have netted $621,500—a return on initial investment of an enviable 1,300 per cent. Sadly, Computer rebuffed my repeated attempts to interview him, and even instructed his underlings to avoid me altogether. Some months later, I again tried to reach him through my local journalist contacts, but received the following curt riposte: “Impossible. He is a Puntland government fugitive—will be shot or arrested on sight.”

I’ll wager that Computer will see the soldiers coming from miles away.

* * *

In many ways a typical Gulf of Aden hijacking, the

Victoria

was an ideal subject for a profile of a pirate gang. As I delved deeper into the operations of the

Victoria

gang, I gradually became aware of the similarities to a like-minded study conducted by then-University of Chicago grad student Sudhir Venkatesh and popularized by authors Steven Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner in their bestselling book

Freakonomics

. In

Freakonomics

, Levitt and Dubner explore the detailed financial statements of an inner-city Chicago crack gang, revealing that the most junior members of the gang, the street dealers—or, as Levitt and Dubner call them, the foot soldiers—earn a paltry $3.30 per hour. The point they make is simple: despite the glamorized wealth of the drug trade, very few people make a decent wage out of dealing crack.

A similar point can be made about Somali piracy. Media attention has focused on the multimillion-dollar ransoms paid to the pirates, but most of the members in a pirate gang earn barely more than a crack foot soldier. Once the ransom money is divided up, the middling amount received by the average gang member is quickly either spent or bled away by family and friends.

Even in the most high-profile hijacking cases, the ransom amounts can be deceiving. When Garaad complained (in

Chapter 5

) that everyone involved in the MV

Faina

hijacking “only got a few thousand,” he probably had a legitimate grievance. By the time the five-month-long negotiation for the

Faina

ended, four or five distinct pirate organizations were involved, and over a hundred pirates were stationed on board the vessel itself. Even though the $3.2 million ransom paid to release the ship was the largest at the time, if the

Victoria

is any guide, virtually the entire amount could have been swallowed by the costs incurred during the

Faina

’s captivity.

The parallels between crack and piracy go beyond finances. Like drug dealing for inner-city youth, piracy provides one of the few avenues for a young Somali to gain status and respect. As Levitt and Dubner point out, crack foot soldiers are willing—in the short term—to accept a job paying far less than minimum wage because they view it as one of their best chances for long-term socioeconomic advancement. In Somalia, where the prospects for career development are undeniably worse than in even the most destitute of American ghettos, it is hardly surprising that piracy is the profession of choice for many ambitious young men.

15

The Road’s End

O

N MY FINAL DAY IN

E

YL, WE LEFT THE

F

AROLE COMPOUND IN

Badey and passed through Dawad for the last time, stopping for a cup of morning

shah

in a cramped bodega. As we were sipping our teas, a maroon-and-chrome Land Cruiser pulled up to the shop. A few kids turned to me excitedly and pointed: “Burcad, burcad!”—pirates, pirates! The Land Cruiser revved its engine and sped away.

Dhanane, which lay on a promontory visible to the south of Eyl, should have been a half-hour drive down the coast. But as no such road existed, we were forced to strike inland for an hour and a half before turning onto a path running roughly parallel to the shoreline. As we headed back towards the ocean, our 4×4s began the arduous climb back up the ridge, their insides rocking and jarring like flight simulators. The “path” we were on barely deserved the name; it was fighting a losing battle with the mountain, asserting itself only in brief stretches between jutting slabs of rock. Stunted myrrh trees dug into the sandy soil, their roots tenaciously gripping the sloping rock face.

Upon reaching the top of the plateau I was again shocked by the stark change in landscape; it was completely desolate, reminiscent of the surface of Mars. The continual harsh winds had swept the plain clear down to the rock, leaving it denuded of vegetation save for scraggly patches of shrubs barely more substantial than lichens. Against this empty landscape, reddish termite mounds assumed monolithic proportions, rising out of the ground like a string of sand fortresses guarding the passage. The bluish haze of the Indian Ocean was visible in the distance, barely distinguishable at the horizon from the brown of a seaside bluff. Slightly further to the south, nestled in front of a chalk-streaked cliff jutting into the sea, lay the town of Dhanane. We bounced along for another fifteen minutes, but the headland hardly seemed to get any closer; with no reference points, it remained an unchanging mass in the distance.

As we approached the town, a pair of 4×4s rumbled up the path towards us, likely a pirate supply convoy returning to Garowe after making a delivery in Dhanane. On the trail of Somali pirates, there was no sign more encouraging than near-new Toyota Surfs, the closest thing the pirates had to a company car. As the Surfs pulled alongside us, a driver-side window rolled halfway down and a few hands extended cautious greetings, which were reciprocated by our driver, Mahamoud.

“If you weren’t here, we would capture or shoot them,” Colonel Omar declared. I could not tell if he was joking.

If Eyl was the Wild West, then Dhanane was the wilderness—a hamlet of huts beginning about fifty metres back from the cliffside, many with green-tinged thatched roofs the colour of a corroded penny. Rising ten metres above the ground, the spire of a lone radio tower dominated the town; a nearby mosque was the only stone building in sight. It was as if humanity had attempted to scratch proof of its existence into the bare rock, a testament that would be washed off the cliff by the first torrential rain. Of course, such a rain would never come in Somalia, but it seemed a miracle that the flimsy huts could withstand the vicious winds of the

hagaa

.

A few faded NGO signs marked the entrance to the village, probably planted during a brief detour by the tsunami relief expedition sent to Eyl in 2004. We drove slowly through the centre of town, past dwellings spilling rough-and-tumble towards the sea. The village was completely deserted, its inhabitants not yet awakened to our presence. We stopped the vehicles short of the cliff and strolled down to its edge.

The bluff on which Dhanane was situated wrapped around to cradle a large inlet at its base. Walking to the edge of the cliff, I gazed onto a white sand beach fifty metres directly below; the drop was precipitous, but a near-vertical path allowed access to it. Waves of rolling blue turned gently to green as they broke against the shallow incline of the beachhead. Subtract the wind, install a few shark nets, bring an end to the civil war, and Dhanane would have made a fine spot for a seaside resort. On the sand stood a solitary building resembling a beach house, surrounded by overturned fishing skiffs. There were no fishermen in sight, and it was easy to understand why; the winds in Dhanane were even stronger than those in Eyl, and in the horseshoe-shaped bay below they must have been close to tropical storm force. A pirate skiff would have been hard-pressed to make it past the first salvo of waves breaking against the shore.

My bodyguard Said grabbed my arm and pointed eagerly leftward on the horizon. There, almost obscured by the edge of the bluff, was the object of my trip to this obscure little town. It was the Dutch-owned cargo ship

Marathon

, hijacked on May 7, twenty-eight days previously, while transporting coke fuel through the Gulf of Aden safety corridor. There were eight Ukrainian crew members on board.

As I snapped away at these various sights, digital SLR in one hand, camcorder in the other, a number of young men detached themselves from the huts above and made their way to the cliffside to observe. They soon wandered over to Omar and began to question him.

“Why did you bring this spy?” one of them said. “Tell him that it’s a Yemeni fishing ship,” pointing to the

Marathon

, clearly hoping that I would go looking somewhere else for Europeans. He was hardly to blame for this cynical attitude, given the international media’s failure to spare any ink for the scores of unreported attacks on Yemeni fishermen.

The curious youth soon tired of their windy watch-keeping and receded back into the town, glancing back at me over their shoulders. We began to wind our way back up through the village, the orange tarpaulins of the hut walls snapping violently as we passed like sails luffing in the wind. We came to a small enclosure ringed by piles of stacked brushwood, where a few townspeople had gathered beside a small outdoor kiosk. Omar motioned to a thatched lean-to nearby, and I pushed through the canvas entrance and into the dark, cool interior. There were a few plastic chairs scattered in a circle around the wooden strut holding up the hut, and Omar and I sat down.

Two members of the local pirate chapter lounged on the woven mats lining the dirt floor of the lean-to. One, whom I later learned was the group’s accountant, had recently arrived from Garowe in anticipation of the impending delivery of the ransom money; he lay curled in a semi-foetal position, his cellphone clutched in his left hand. Another member of the gang, sporting an oversized UNICEF T-shirt, joked that he had renounced piracy and was now working for the United Nations. Discarded khat leaves lay in two messy piles at his feet, flanked by several packs of British Tobacco cigarettes. Ombaali reclined next to him with his 7-Up in hand, and they chatted like old comrades.

I had no idea whose hut this was or who had invited us in, but soon a man dressed in brown khaki pants and vest entered and greeted us. His name was Dar Muse Gaben, and he soon revealed himself to be a high-ranking member of the local group, the man in charge of organizing and delivering supplies to his colleagues aboard the

Marathon

. Gaben took his work into his off-hours, it seemed, because he soon returned with a round of

shah

and several warm 7-Ups for Omar and me. After some prodding, Gaben cautiously agreed to answer a few of my questions.