Pirates of Somalia (31 page)

Read Pirates of Somalia Online

Authors: Jay Bahadur

Tags: #Travel, #Africa, #North, #History, #Military, #Naval, #Political Science, #Security (National & International)

14

The Freakonomics of Piracy

M

ODERN SCIENCE MIGHT TAKE A SCEPTICAL VIEW OF

C

OMPUTER’S

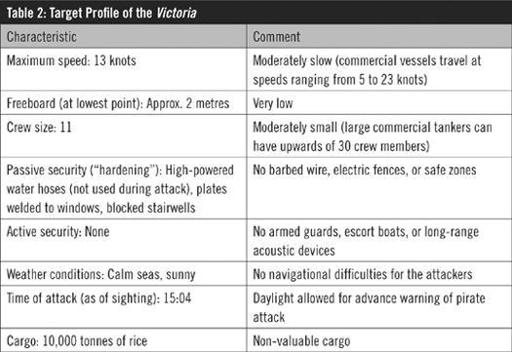

psychic talents, but it is hard to argue with success, and his clairvoyant directions could not have been more effective in leading his pack to a helpless victim. Despite travelling in the Internationally Recommended Transit Corridor (IRTC) and being within 80 to 160 kilometres of a Turkish warship when she was attacked, the

Victoria

was captured with relative ease. What made her such an easy mark? It turns out that the vessel possessed several attributes that rendered her particularly vulnerable, listed in

Table 2

.

In short, the

Victoria

was slow, low, and undermanned. The disadvantage conferred by her lack of speed is evident: with a thirteen-to-twenty-knot edge, Mohamed Abdi’s team overtook the

Victoria

less than forty minutes after they were sighted. Once they reached her in advance of the Turkish attack helicopter, the difficult part was over. The pirates must have been delighted to find a freeboard of only two metres, close to the lowest possible for a ship that size. Finally, the

Victoria

’s small crew not only meant fewer variables to interfere with a smooth boarding (such as crew members blasting the attackers with high-powered hoses), but also fewer sets of eyes on deck watching for pirates.

The only element favouring the

Victoria

’s crew was the timing of the hijacking. Pirate attacks most often occur at dawn and dusk—to take advantage of reduced visibility—and the fact that the pirates chose to attack in the middle of the afternoon meant that the crew was afforded an unobstructed view of the oncoming attack craft.

* * *

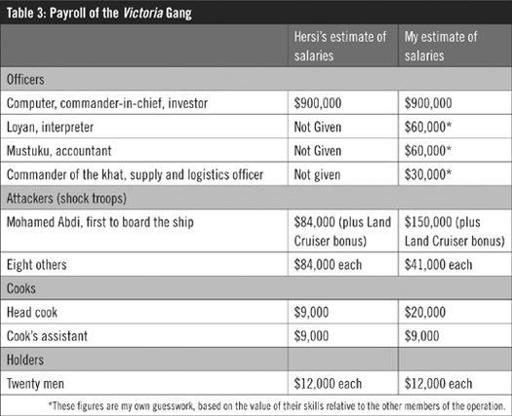

Hussein Hersi’s insider account in

Chapter 12

provides a detailed sketch of the

Victoria

gang, both from an operational and a financial standpoint. But can we trust his information? “Pirate math” frequently does not add up, so I will subject it to an external audit.

The first step is to establish the full size of the gang. Former hostages Traian Mihai and Matei Levenescu both stated that there were usually twenty pirates on board the

Victoria

on a given day, but provided two different figures for the number who congregated on the days leading up to the ransom delivery: thirty-two, according to Mihai, and thirty-eight, according to Levenescu. If, as Hersi said, each member of the operation was required to be on board the ship in order to receive his share (and it is hard to imagine any gang member would

not

want to be present for the big day), then thirty-two to thirty-eight individuals represented the total membership of the gang; I have averaged the two estimates to reach a figure of thirty-five. Of these, Hersi’s and Levenescu’s testimonies account for fifteen: Computer, Loyan the interpreter, Mustuku the accountant, the “commander of the khat,” nine attackers,

1

and two cooks. Presumably, the remaining twenty men were the “holders” who guarded the ship and crew, in rotating shifts, once it had been brought to Eyl.

* * *

Hersi supplied some detailed—though incomplete—payroll figures, including the salaries of Computer ($1.5 million), the nine attackers ($140,000 each), the twenty holders ($20,000 each), and the two cooks ($15,000 each). However, Hersi’s estimates assumed a $3 million ransom, while the actual amount turned out to be only $1.8 million. To reflect the reduced total, I have scaled down each of Hersi’s numbers by 40 per cent: Computer would have received $900,000, each attacker $84,000, each holder $12,000, and each cook $9,000. Regrettably, Hersi did not provide the incomes for the interpreter, the accountant, or the commander of the khat.

Unfortunately, these numbers sum to significantly more than $1.8 million even before including Loyan, Mustuku, and the commander of the khat, all of whom presumably collected respectable salaries. Where are Hersi’s mistakes? Computer’s 50 per cent share is probably accurate—it is well in line with the “industry standard” for the sole investor in a gang. The salaries paid to both the holders and the cooks are also probably roughly accurate; much less would not attract young men to a job that demanded almost two months of their time, and, while not as dangerous as that of the attackers, still carried substantial risks. The only remaining explanation is that Hersi overestimated the amount received by the attackers, to the extent of about $40,000 per man.

Matei Levenescu, it is important to note, dissented from Hersi’s account in two important ways. In his eyewitness description of the air delivery and subsequent partitioning of the ransom, Levenescu recalled that one member of the attacking team received a $150,000 share.

2

It is almost certain this was Mohamed Abdi, the first attacker to board the vessel. Abdi’s higher share of the spoils was not the only indicator of his elevated status within the gang—he also served as the pirates’ media spokesman, providing details of the ransom amount to journalists and confirming the ship’s release. Levenescu also differed from Hersi in reporting that the pirates’ cook—only one, he said (plus an assistant)—received a $20,000 share. I have accepted Levenescu’s first-hand version of events over Hersi’s, most of which was second-hand.

Using the combined testimony of Hersi, Levenescu, and Mihai, I was able to piece together a rough estimate of the

Victoria

gang’s payroll (see

Table 3

). These figures debunk the myth that piracy turns the average Somali teenager into an overnight millionaire. Those at the very bottom of the pyramid, the holders and the cooks, barely made what is considered a living wage in the Western world: to maintain a pirate crew of twenty, each holder would have spent roughly two-thirds of his time, or 1,150 hours, on board the

Victoria

during her seventy-two days at Eyl, thus earning an hourly wage of $10.43. The head cook and assistant by all accounts never left the ship, and therefore would have earned wages of $11.57 and $5.21 per hour, respectively (a high-end restaurant meal in Somalia, for comparison, goes for about $10 to $15).

Even the higher payout earned by the attackers seems much less appealing when one considers the risks involved. The moment he steps into a pirate skiff, an attacker accepts about a 1–2 per cent chance of being killed, a 0.5–1 per cent chance of being wounded, and a 5–6 per cent chance of being arrested and prosecuted.

3

By comparison, America’s deadliest civilian occupation, king crab fisherman, has an on-the-job fatality rate of about 0.4 per cent.

4

Granted, the $41,000 that an attacker earns buys a lot more in Somalia than it does in the United States. But given that most blue-collar pirates have a virtual army of destitute friends and relatives they are expected to share with, they do not typically experience a sustained rise in their standard of living.

As in any pyramid scheme, the clear winner is the man at the top. Computer may or may not be all-knowing, as his reputation claims, but he certainly seems a lot savvier than the men working for him.

* * *

So much for income, but what about the gang’s expenses? Hersi claimed that the gang spent $500,000 on supplies—purchased on credit—while awaiting the ransom. On the surface, this seems like an exorbitant sum. Where could it all have gone? The gang’s operating expenses fell into four categories, in order of decreasing cost: khat, transportation and fuel, weapons, and food and beverage. Since everything was paid for with credit granted on the basis of the forthcoming ransom, the “pirate price” for these various goods and services was approximately double the norm.

Khat was by far the biggest drain on the group’s balance sheet. The crew did not habitually chew khat with their captors, but each of the twenty pirates on board would have easily consumed one kilogram per day, given not much else to do with his time. The Chief noted (to his astonishment) that the pirates paid $38 per kilogram for the drug—or $76, at credit prices.

The group’s transportation and fuel expenses included three items. Hersi related that the gang had two Land Cruisers on permanent retainer, primarily to transport members between Garowe and Eyl. In Puntland, a Land Cruiser rents for $200–$300 per day; assuming the pirates paid twice that, the cost of their premium shuttle service would have been close to $60,000.

The second item was the diesel used to power the

Victoria

’s emergency generator. During the first stage of her captivity, the crew used this generator to provide the electricity for everyday conveniences: lights, the mess, air conditioning, and so on. But by June, the

Victoria

’s supply of diesel fuel had been depleted. The crew then resorted to the extremely inefficient process of generating electricity using the ship’s main engine, until, shortly after I left Eyl, the supply of bunker fuel reached critically low levels and the engine had to be shut down. At this point, the pirates began to ferry drums of diesel from the shore to power the emergency generator, which, according to Levenescu, they only turned on at night. Marine emergency generators typically have a power output of around a hundred kilowatts, and consume twenty-five to thirty litres of diesel per hour at full load. Given the expense, scarcity (due to the remoteness of Eyl), and logistical difficulties in moving large amounts of fuel from the skiff to the deck of the ship, it is likely that the pirates did not operate the generator above half its full capacity. If they ran the generator between 7 p.m. and 5 a.m., at a cost of about $1.50 per litre of diesel (double the norm), they would have spent $225 on fuel during each of the

Victoria

’s final twenty-five days in captivity. Added to this bill was $6,800 for the four tonnes of diesel the pirates brought on board to power the ship’s fuel heating system, in preparation for the

Victoria

’s release.

The gang’s third transportation expense consisted of fuel for the supply skiffs, which two to three times daily ferried people and provisions to and from the

Victoria

. During my trip to Eyl I was lucky enough to witness the loading of an early morning transport (including the unfortunate goat), which was powered by a twenty-five-horsepower outboard motor. Assuming that each round trip took about fifteen minutes, the daily gasoline consumption for such a motor would have been about eight litres. With local gasoline prices at roughly $2.50 per litre, the boat would have consumed $20 of fuel per day.

As the

Victoria

’s captivity wore on, the gang became increasingly paranoid of outside attack. To defend themselves, Hersi related that they purchased two PKMs—standard-issue Soviet machine guns—and three thousand rounds of ammunition. Such weaponry is surprisingly expensive, even in Somalia; assuming that they paid twice the regular price, the total cost of these arms would have been around $30,000.

Food and drink were the least of the gang’s expenses. Hersi said that the gang purchased and slaughtered two goats daily: one for the guards on the ship, and the other for the crew. Breakfast might have consisted of goat liver, or

beer

, perhaps served with

injera

bread in an onion and potato broth, and lunch and dinner would probably have been fried or minced goat meat served on pasta or rice (supplied free from the

Victoria

’s overflowing hold) with bell peppers, potatoes, tomatoes, lettuce, bananas, and limes. Accompanying the meals (and each khat session) would be sweet tea, 7-Up, goat’s and camel’s milk (to sop the rice), and bottled water. In Garowe, a goat costs roughly $25; using credit in the remoteness of Eyl, the pirates paid the inflated price of $100–$150 per goat. The cost of all other ingredients would have added up to no more than $100 per day.