Plymouth (23 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

The expedition was a failure. Many of the soldiers died of plague, food poisoning or exposure on the ill-equipped vessels. On the ships’ return into the Sound, hundreds of putrid corpses were thrown into the harbour, and the narrow streets were filled with homeless soldiers, many wounded, and all stinking and diseased. Mass graves awaited them. The captains had to sell their stores to feed the sick, with no support coming from the King. James Bagge was vilified in Parliament, accused not only of embezzlement but of plundering a French vessel in Plymouth Sound to line his purse. Rumours spread that the monies went to the Duke of Buckingham, and to protect his friend, King Charles I dissolved Parliament to prevent his impeachment. Plymouth joined Parliament in their censure of the King and his allies.

Buckingham then led a force to defend their protestant allies the Huguenots at La Rochelle, under attack from the French, but it was another disaster. The ill-fed and diseased soldiers mutinied in Plymouth and rebelled again when one of their number was sentenced to be hanged, the mob tearing down the gallows. At La Rochelle, as the ill-equipped English were forced to retreat, thousands drowned. Around 3,000 men, over half the expedition, were killed, and Buckingham’s popularity plummeted to an all-time low. Again sick and wounded men were brought to Plymouth. The council issued an order to try to prevent them landing in Plymouth, but still the diseased men were brought ashore.

Battles between Parliament and the monarch came to a head in 1642, and civil war was declared. Cornwall sided with the King, while Devon sided with Parliament. At first, the administration at Plymouth was Royalist, under Governor Astley. However, the King made the terrible mistake of calling Astley to join him as a Major General in the Royalist army. The moment Astley departed, Mayor Francis and his Puritan allies took charge of Plymouth and declared it for Parliament. Although the rest of Devon and many ports around the country fell to Royalist forces as the war progressed, Plymouth remained the only port for Parliament throughout the Civil War, fiercely defending itself against the King in years of siege and hardship.

By 1642, Plymouth was a strongly walled town, with the fortifications built in the time of King Henry VIII still present on every headland around the Sound. The mayor decided that an outer line of fortifications was necessary, along the natural northern ridge that runs west to east from the old Stonehouse creek north of Mill Bay, to Lipson and Tothill – a line of about 4 miles that forms a crescent around the town. Every man, woman and child was forced to work to build the fortifications, digging trenches, building earthworks, and supplying the soldiers with ammunition, food and drink. ‘Strong drink’ was provided for when the fighting got bad – and it got bad.

Every man in Plymouth signed an oath to die in defence of the town rather than see it taken by the King, and as the Royalists took Devon, the people grew ever more desperate to defend themselves. Rumours circulated of what happened to the inhabitants as other besieged towns fell to the Royalists – horror stories of children slaughtered, women raped and men sold into slavery. These may have been exaggerated, but they also contained a kernel of truth.

Soon the Plymothians were hemmed in by Royalist troops at Saltash, Plympton and the headland now called Mount Batten, and Plymouth became increasingly isolated. Refugees from across the South West, fleeing the King’s forces, arrived in great numbers in Plymouth, swelling the already overcrowded town to a population of 10,000. Living conditions inside the town soon became unbearable, with only the port able to supply food and fuel to the trapped inhabitants.

Warships at the time of the English Civil War. Ninety mustered in Plymouth Sound in 1625. (With kind permission of Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, Library of Toronto)

The King’s men blocked the leat from Dartmoor that provided Plymouth with its fresh water, and plague and typhus soon flared up. Firewood became unobtainable. Yet they refused to surrender. When a Royalist trumpeter arrived at the town with a request from the King’s forces for their surrender, he was whipped, beaten, imprisoned overnight, and then sent back with instructions never to visit the town again.

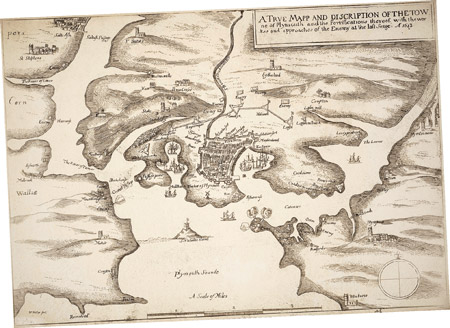

1643 siege map of Plymouth, by Wenceslas Hollar. (With the kind permission of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto)

Plymouth was populated by men of military expertise and daring, often fuelled by Puritan passions. Repeatedly they led enthusiastic raiding parties beyond the line of forts to take on the Royalists.

Aware that the Royalists had established their headquarters at Modbury, east of Plympton, Colonel Ruthven, a Puritan of the Plymouth militia, mounted a bold plan. Ruthven took 300 mounted men north and then east, circumventing the motley Royalist army in Plympton and, in the mists of dawn, took the Modbury headquarters by complete surprise. With swords and pistols, Ruthven’s men charged on Modbury, hitting the Royalist command post with such force that the 900 Royalists posted there immediately scattered. The Royalist senior officers, holed up in a local mansion, surrendered when Ruthven ordered his men to set fire to nearby outbuildings, the flames and smoke heading for the main house.

While Ruthven’s fervent Puritans desecrated the local church, removing all ‘heretical’ images and iconography, the Plymouth forces captured the senior Royalist officers. Ruthven’s genius was then to draw the remaining Royalist army – regrouping now for a counter-attack – to follow him east to Dartmouth, while the majority of the prisoners and Ruthven’s men actually travelled west to Plymouth through Plympton. Splitting the party had the Royalists fooled, and Plymouth triumphed with the largest cache of Royalist senior officers ever captured.

Over the four years of the siege, there were many of these little victories, but the greatest victory for the Plymouth forces was to come with the Sabbath Day fight.

![]()

A strange ghost from the English Civil War still haunts the Mount Gould Hospital, located near the line of forts once attacked by Prince Maurice in the Sabbath Day fights. After many strange occurrences, one male member of staff reported seeing a white lady in a patient’s room. As he watched, the white lady disappeared through the wall. Though the patient in the room was well that day, he was dead by morning.

![]()

Prince Maurice – nephew to King Charles I and a man renowned for his atrocities against civilians in the wars in Europe – had been put in charge of breaking the siege at Plymouth. To defend their eastern borders, the Plymouth forces had built a new earth-work called Laira Point, overlooking the tidal Laira Creek that ran into the Plym. Laira Creek ebbed and flowed through a deep valley on the other side of the steep north-eastern ridge, but Prince Maurice saw this as a suitably weak target to break the siege. He couldn’t have chosen a worse location to attack.

In the dark, the lonely sentinels at Laira Point were engulfed. Suddenly Royalist forces were upon them, surrounding them from every side at once, and putting the Parliamentary supply ships moored in the Plym River at great risk. Hearing the alarm, however, Plymouth mustered its forces to retake Laira Point: unseen in the darkness, they approached the fort from the south, at Tothill Ridge, with a surprise counter-attack. Now it was the Royalists’ turn to be surprised: the raiders suddenly found themselves under attack by 150 mounted defenders. However, despite this initial victory, the Plymouth forces broke under pressure, and they were forced to retreat west to Lipson Fort, near Freedom Park. Captain Wansey of Plymouth was shot in the fierce fighting.

The Royalists, spurred on by their triumph, charged west to take the town, but the Plymouth forces unexpectedly regrouped and ‘swept all before them like a roaring torrent’. The King’s men retreated, only to discover that the tide had turned behind them and now the Laira Creek was impassable. Trapped against the deepening rush of water, Maurice and his men floundered on the ridge overlooking the Laira, their horses plunging into the mud, riders riddled with shot from the attacking Plymouth forces. Hundreds of the Royalists died, drowning, sliding down the steep embankments into the muddy waters. At this point they were also targets for the ships still in the Plym estuary and many of the King’s men fell into the hands of the Plymouth fighters. For many centuries, Plymouth’s victory – the ‘Great Deliverance’ – was celebrated on 3 December, and with a commemorative monument at Freedom Fields.

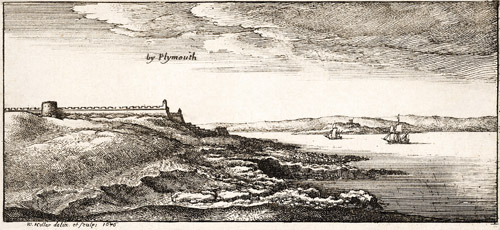

Plymouth Sound, showing the Civil War fortifications in 1646. (With the kind permission of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto)

In disgrace, Prince Maurice moved on, and in 1644 Sir Richard Grenville was appointed to oversee the siege on Plymouth. Again Sir Richard tried to intimidate the town into surrender, but his words were met with scorn. He had arrived late in the English Civil War after brutally attacking the rebellious Catholics in Ireland. Initially Grenville had declared himself for Parliament and had been appointed to lead an army to attack the King, but at the last minute he changed sides, taking his forces – and Parliament’s money – with him to join King Charles. Grenville was branded the worst kind of traitor: a turncoat, ‘skellum’ and a rogue.