Plymouth (20 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

1914-1918

A WAR TO END ALL WARS

B

RITAIN DECLARED WAR

on Germany on 4 August 1914, and the workforce at the Devonport dockyards immediately doubled. Around 9,000 extra men and women worked on building new ships, including the Q-ships designed to attack the German’s U-boats and testing the new K-class submarines. Submarine K6’s trial was disastrous, as the vessel submerged in the Sound and then refused to rise from the seafloor for two hours. The defect was repaired eventually by the inspector of engine-fitters, who was fortunately aboard, but the yard men from Devonport refused to go down in a submarine again.

At the outbreak of war, Salisbury Road Elemental School, like many other schools, became a temporary hospital. All the desks were unscrewed from the floors and replaced by 280 beds, a treatment centre and a neurological department. Less than a month later, the first 100 British and German casualties arrived from northern France.

The

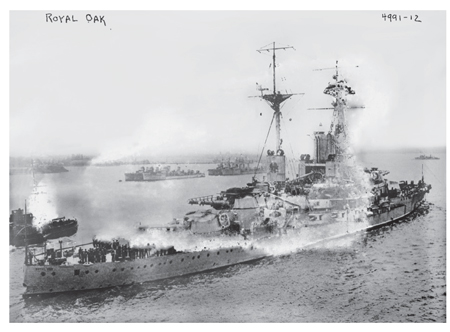

Royal Oak

. (LC-DIG-ggbain-29189)

The greatest early disaster for Plymouth was the loss of the Devonport-built and manned HMS

Monmouth

in the Battle of Coronel, lost off the coast of Chile with no survivors.

At the Battle of Jutland in May 1916 the Royal Navy lost 14 ships and 6,274 men. Five of the lost ships and four of those badly damaged were Devonport-manned. The

Indefatigable

was sunk with only two survivors. The Devonport-built the

Royal Oak

, a 27,500-ton battleship, survived the battle and continued to be deployed until the beginning of the Second World War.

All major roads into Plymouth were heavily guarded against spies and saboteurs. By 1916 there were genuine fears that Plymouth would suffer aerial bombardment from German Zeppelins operating from bases in North-West Europe – and one alarm, fortunately false, brought the town to a standstill. An unidentified naval plane flew over the coast bringing the evening rush hour to a halt. Crowds of residents remained trapped in the streets and in the train stations for several hours before it was revealed that the plane was ‘one of ours’.

A Zeppelin landing in front of Count Zeppelin, the inventor, and the Crown Prince. Fear of aerial attack brought Plymouth to a standstill in 1916. (LC-USZ62-44993)

Meanwhile, soldiers from the Devonshire Regiment were battling in Europe, many of their recruits from Plymouth and most enlisted in Plymouth or Devonport. Atkinson’s

The Devonshire Regiment, 1914-1918

is a remarkable book. Tragically, however, over half of its 742 pages are made up of lists of the dead: in the 1st Battalion alone, over 2,600 men died, 291 of them officers.

![]()

Amanda Bradfield, just eighteen, was murdered by her mother’s lodger, James Honeyands, in 1913. Amanda was married to a naval stoker (serving on the HMS

Monmouth

) when she went for a drink in the Courtenay Arms with Honeyands. They quarrelled. The argument continued into the street outside, where Honeyands pulled out a revolver and shot Amanda twice in the chest. He then tried to kill himself, but the revolver jammed. He was apprehended by passers-by.

Amanda did not die immediately, but lingered in hospital for ten days, on one occasion coughing up one of the bullets. Honeyands was charged with murder and hanged on 12 March 1913.

![]()

In 1917 the Devonshire Regiment faced a formidable German line at La Coulette. The Germans’ position was very strong, the ground flat and devoid of cover for 2,000 yards, with wire entanglements that were unusually thick and the railway embankments nearby proving to be deadly positions for the flanking fire that was bombarding the Devonshire troops. The German artillery at the rear of this formidable fortress was as yet untouched by the British attempts to bombard it – the British artillery was still far behind the ground forces. Atkinson describes the scene: ‘despite these formidable obstacles and fatigue and hardships the battalion had endured of late, the men went forward with the utmost dash. From the first, the Devons fared none too well. The hostile barrage caught them in their assembly positions and inflicted many casualties before they moved.’

![]()

When the German fleet surrendered in 1918, Sir Francis Drake’s famous drum at Buckland Abbey, just outside Plymouth, beat a ghostly tattoo. Sir Francis took the drum with him while circumnavigating the world. Legend says that if ever England is in danger, the drum will sound and Sir Francis Drake will return to defend us.

![]()

However, the Devons made a ‘fine effort’, capturing the first line of German trenches, and ‘for a short time the parties who had succeeded in entering the German trenches looked as if they were going to achieve the impossible’. However, German reinforcements arrived, and within a few hours it was reported that only two officers remained unhurt. The party in the German trenches were under fire and ‘barely holding on’. By mid-afternoon, the surviving Devons were digging in only a few feet from their starting point that morning. Over seventy were killed in the fighting, with one hundred and sixty wounded.

At the Battle of Fresnay, eighty-six men and officers were killed – including Captain Leonard Maton, who, having being wounded in previous battles, had been ‘retired’ to a desk job – but he refused to leave the front line. He was killed with his men on 9 May 1917.

One Plymouth man in the midst of these battles was Sergeant Thomas Henry Britton, who was born in Plymouth and enlisted at Devonport. The 1st battalion of the Devonshire Regiment were sent in to relieve the front line at the Somme – their task was to consolidate the position, rescue the wounded and rebuild the trenches, all under heavy shelling. They bravely fought on for three continuous days under fire, suffering 100 casualties, including Thomas. Every centimetre gained in ground at the Somme cost the British two lives.

Reginald Colwill was with the 2nd Devonshire Battalion in France and describes in detail the horror and the triumphs of their final year in battle. His tone is remarkable for its cool descriptions and also its honesty. He heaps great praise on Major Cope, their leader, but also on the men who braved the battles with fortitude and humour: ‘Who can explain the psychology of these men, who could face the extreme probability of death with smiles... It was the men who smiled who did great things.’

In March 1918 the Devons had established a headquarters at Brie, but the Germans were rapidly advancing on the other side of the river. After a failed attempt to bomb the bridge, the Devons were told to hold the bridge at all costs and prevent the Germans crossing the river. Now the Devons were the only force to stop them. But the Germans broke the British battle lines further up the river, at Éterpigny, and suddenly the Devons were forced into a retreat, with the enemy ‘hammering on our right flank for all he was worth’.

‘E’ company were the last to move out, with their Lewis gunners blasting at the oncoming German forces. One gunner had his leg shattered by a shell fragment, but kept on firing to prevent the Germans crossing the bridge. For half an hour he stayed at his post, blazing away, firing drum after drum of ammunition into the advancing enemy, taking a ‘fiendish delight in watching the deadly effect of his fire’, knowing all the while that his company was evacuating its position. This unknown hero not only managed to hold his position, but he even managed to escape and survive the battle.

Suddenly one platoon of ‘C’ company were entirely surrounded by Germans and had to be left to their fate – it was a tough decision by the commander, but ‘it would have been folly to consider throwing men away on merely heroic exploits’.

When ‘D’ company came under attack, Colwill praised their self-defence: ‘God! How they fought... Like demons possessed, they cut and hacked, fighting their way out, inch by inch. In time they succeeded though they left many dead behind them.’

Their next line was near Ablaincourt, facing east. Suddenly there were German soldiers coming over the hills towards them, and ‘the troops opened fire and hit a lot of them. Yet, on they came, line followed line... closer and closer every minute.’ But ‘D’ Company was successful in its attack, inflicting an appalling slaughter: 200 German soldiers lay dead in front of them in less than an hour.