Plymouth (8 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

The next morning, Elizabeth tried to claim that her husband had perished suddenly of natural causes during the night, but the neighbour spoke out and the body was exhumed: clear signs of strangulation were revealed. Elizabeth and her accomplices were subsequently brought before Judge Glanville for sentencing. He had them all hanged. The murder of ‘wealthy Page’ and the trial of Glanville’s daughter were later transformed into a play called

The Lamentable Tragedy of Page of Plymouth,

in which Glanville’s daughter re-enacts the vicious killing of her husband.

However, even at the time the story of the father Glanville executing his own daughter was considered to be untrue. It was possibly confused with the more reliable story of Judge Hody, who sat in judgement on the public assizes during the reigns of Henrys VII and VIII. Hody was presented with his own son, Thomas, who had confessed to a capital crime. He was forced to pronounce a sentence of death upon the boy. Thomas killed himself in prison before the executioner could take him, whereupon the father denounced his son as a degenerate. He refused to attend the boy’s funeral – and since that day, it is said, no boy has been christened Thomas in the Hody family.

Returning to the Glanvilles and the ‘wealthy Page’: in St Andrew’s church, near the Guildhall, the church officials were breaking the ground near the communion table to inter the body of a lady called Lovell, when, to their surprise, they discovered another coffin already buried there, with the inscription of ‘wealthy Page’. When opened, Page’s remains were found to be in a surprisingly perfect state, but crumpled to dust on being exposed to the air. The coffin and its contents drew hundreds of curious Plymouth citizens over the next few days, with many relics stolen as souvenirs, including the nails from the coffin. So if the ‘wealthy Page’ existed, perhaps the story of Judge Glanville could be true.

There is another version of the story, however, telling of a relative of Judge Granville, a Tavistock merchant by the name of Glandfeeld. Glandfeeld’s daughter Eulalia fell in love with her father’s lowly assistant Strangwich, but Glandfeeld forced his daughter to marry the wealthy Page instead. After the marriage, Strangwich visited Eulalia as her lover, and they plotted to kill her husband, bribing two servants to do the deed. The servants found Page in his bedchamber, stifled his mouth with a handkerchief and, throwing him onto the bed, broke Page’s neck. When apprehended, Eulalia confessed all to the mayor and Sir Francis Drake – and if a story is to be embellished, who better to include? The lovers were then hanged at Barnstaple, as Exeter was suffering another outbreak of plague.

But if Judge Glanville’s daughter was not the culprit hanged by her own father, then why does Glanville, tormented, apparently still haunt his Devon family estate, Kilworthy House? And why does his daughter also haunt the estate, appearing as an ominous spectre, missing her head?

1579-1620

TO BE A PILGRIM

T

HE PILGRIMS OF

the

Mayflower

were not the first English settlers in the New World, but they were among the first to survive the ordeal. In 1579 Sir Humphrey Gilbert claimed the first English base in Newfoundland, comprising mainly Portuguese and French fishing villages, but he sank with his ship in a storm before making it home.

Sir Walter Raleigh, one of Plymouth’s favourite courtiers, then took possession of North Carolina in the name of Queen Elizabeth I, but the first settlement there left 108 emigrants starving. They were then massacred by Native Americans. A second settlement simply disappeared: only the bones of a single man were ever found.

The third wave of settlers, led by John White, again disappeared. John briefly visited Plymouth to get supplies and returned to the American settlement to find everyone in his colony had vanished – including his wife and their daughter. Search parties found no trace, but there is a story that pale, red-haired children were born to a native tribe not far north of John White’s settlement... These small groups were easy prey to the natives.

In 1605 Captain Weymouth arrived in Plymouth, having explored the St George’s River and Penobscot in the New World and returning with five Native Americans on board (taken by force during failed negotiations with their tribes). Tisquantum, Manida and Shetwarroes were handed over as a prize to the commander of the Hoe Fort, Sir Ferdinando Gorges, who taught them English and forced them to stay with him for three years. Two of the natives, Manida and Shetwarroes, then helped the Plymouth Company establish a settlement in Maine, but the capture, kidnap and treatment of these first allies did little to secure the natives’ trust. Cold, disease and famine eventually brought yet another failed colony limping back to Plymouth.

Captain John Smith, an adventurer, created a more positive impression with the natives, though not until he was saved by Pocahontas, the big-hearted daughter of the great chief Powhatan. Smith was dragged before Chief Powhatan and his head placed on a rock, ready for the tribe to beat his brains out. Suddenly, Powhatan’s daughter Pocahontas, just twelve years old, laid her own head on Smith’s – kill him and you kill your favourite daughter too, she told him. Powhatan conceded and let the Englishman live.

Pocahontas saving Captain Smith. (LC-DIG-pga-02687)

Portrait drawn during ‘Mrs Rolfe’s’ visit to England in 1616. (LC-USZ62-8104)

Pocahontas was subsequently captured by the English, as part of hostage negotiations, and she eventually married John Rolfe, a tobacco farmer. She became a Christian and changed her name to Rebecca. In June 1616 Pocahontas (or Rebecca Rolfe, as she was now known) arrived in Plymouth with sixteen of her Powhatan tribe, including Tomocomo, a shaman, who tried to keep a tally of the English he saw by marking notches on a stick, but soon grew tired of it – these English were just too many to count. Probably this was the first time the Native Americans realised that these English settlers were to become a serious threat through sheer weight of numbers.

As she was about to return to her native land, Pocahontas died of a mysterious illness, leaving her infant son in the care of Sir Lewis Stucley (remembered by history as the man who betrayed Sir Walter Raleigh to his death at the hands of King James I’s executioner). Pocahontas’ shaman friend Tomocomo returned to his homeland unimpressed by the English and his brief meeting with King James I, who had not even offered him a present.

With King James on the throne, Plymouth’s fortunes worsened. Elizabeth had been no friend to religious non-conformists in the town, but her Plymouth ‘pirates’ were her fortune and she was always ready to turn a blind eye where money was concerned; her favourite, Drake, was of Puritan stock, after all. James I instead decided to make peace with Catholic Spain and enforced religious conformity throughout England, and a small group of Puritans, with links to Plymouth’s Puritan merchants, found themselves forced to flee to Holland to avoid King James’ militia. In time even Holland became unsafe, and the desperate group of pilgrims applied for a grant of land in Virginia where they might live and worship freely.

Pilgrims aboard the

Mayflower –

little did they realise what horrors awaited them on the coast of the New World. (LC-USZ61-206)

The pilgrims chartered two ships, the

Mayflower

and the

Speedwell

, but the latter failed to live up to its name. By the time they berthed in Plymouth to repair the leaking

Speedwell

, it was agreed that the voyage would be made only on the

Mayflower

, carrying just 102 men, women and children, a quarter of the original number. Half of these weren’t even Puritans but ‘strangers’ replacing Puritan settlers who had decided against the voyage at the last minute. It is impossible now to imagine how they could contemplate taking three pregnant women and twenty-three children on such a perilous venture. Their allies in Plymouth were hospitable, and prayers for a successful voyage were offered. They were not answered: the

Mayflower

set off across the Atlantic on 6 September 1620, and into a nightmare.

A rather fanciful portrayal of the landing on Plymouth Rock, engraved by Joseph Andrews in 1869. (LC-USZ62-4060)

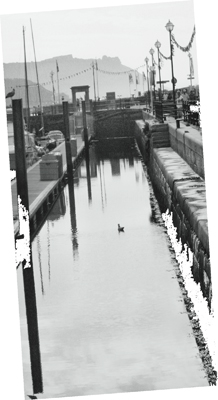

A view of the Barbican, with the memorial archway leading to the Mayflower Steps in the distance. These are not the original steps, as the quays at the Barbican have changed dramatically over the centuries.

For sixty-five days, the

Mayflower

fought her way across the Atlantic in terrifying storms, and the nauseated passengers crowded into a warren of small rooms between the leaky decks, barely 5ft high. Their late departure left them travelling in November, rather than the balmy summer planned. They were out of firewood, two of the settlers were already dead and scurvy was setting in.

The pilgrims were weavers, tailors and shoemakers, not adventurers with the skills required to carve out a settlement in the wilderness. Their success was founded on stoic resolve to create not just a settlement but a new way of living, under the leadership of John Carver, a man of humility, who would successfully bring together the disparate factions on board to work to a common cause.