Polly (15 page)

Authors: Jeff Smith

Farewell to Arms

(1940â3)

M

y brother Bob was called up very early in the war. In fact he was part of the âsecond militia' â though I don't know what that name was supposed to mean and who the âfirst militia' were. Anyway, he got his call-up papers and, I think, was quite looking forward to going away. Well, at that age it was all a bit of an adventure and we hadn't any idea what the war was going to be. The only thing that really terrified him was the thought of telling Mum and what her reaction would be.

At first he kept the call-up secret: he just didn't want her to know in case she got all emotional. Of course, she had to know and I eventually convinced him to tell her. But then, even more important, he refused point-blank to tell her when he was due to go.

âI don't want her blubbing all over the station, it'll show me up,' and so on. I said that he couldn't just go off on his own with no one to go with him to the station and, eventually, he agreed that I could go. I seemed to get all the âgoing-to-the-station-to-say-goodbye' jobs. Anyway, Mum wasn't stupid and it was impossible for Bob to hide all his arrangements, so she soon worked out when he would be going. On the day she got up early, got herself ready, sat down in the kitchen and waited. When the time finally came to go she just stood there and insisted so that, in the end, Bob had to give in.

We had to walk up to Bow to catch the bus to the station; I can't remember what station he had to go from, but Bob was terribly embarrassed all the way. Fancy your mother crying over you as you went off to war. As we approached the bus stop there was a bus drawing in â not our one though â and we saw a man running up a side street for all he was worth. So Mum did no more than step out in front of the bus and tell the driver to wait. The bus driver told her, in pretty broad language, about his timetable and how he had to get to wherever by whatever, etc, etc. In return Mum told him, in just as broad language, about the pressures of wartime, being reasonable, giving people a chance, etc, etc. She would not be moved. Only when the fellow reached the end of the side street he turned left, ran straight past the bus, and headed off up the road to goodness knows where! Good God, that really started it and I thought the war would be coming to an end right there. By this stage Bob was totally beside himself with embarrassment and there was terror in his eyes as he thought ahead to the scene at the station.

Well, we reached the station and there was the platform â a whole mass of people, mainly young men going off to war and young women hugging, weeping, kissing. Not a mother to be seen anywhere. Poor Bob. But then we got the surprise. Mum didn't say or do anything, but as she stood there these girls seemed to gravitate towards her. In no time at all she was surrounded by them, giving a word of comfort here, a little smile there, a squeeze to another. She was the pillar of strength supporting all the sorrow and anxiety that was being piled up on that platform. Looking back, I realise that she had maturity, she represented life going on and, of course, she had experience because she had been through it all before in the First World War. She was the heroine of the hour, the star of the day, and we looked at her with new eyes.

A little later in the war my sister Tiny was working in a menswear shop and really quite liked it. Her best mate was named Marie and was ever so posh. She had, it turned out, been âgiven away' soon after her birth because her mother just couldn't afford to bring her up. Instead she was brought up by her aunt who, it seems, looked after her quite well. For some reason, though, she was desperate to get away. At the time they began the call up for women, mainly into the Land Army and things like that, but they had concessions for those who volunteered. If girls volunteered and joined up together they could stay together and be posted ânear home'. So one day Marie started working on Tiny and suggested that they should join up together. After a bit Tiny agreed and they volunteered. Eventually the day came for them to leave. They went from Stratford station. So there we were, standing on the platform waiting for the

train to start, when suddenly Marie's aunt/mother suddenly cried out to Tiny âto look after my little girl'. This, for some reason, made Mum see red and she led off something chronic at this woman about who looked after who, whose idea it was, her poor child going âoff to the country' and goodness knows what else. It turned out later that Marie was desperate to get away because her aunt's âboyfriend' had started to molest her. Still, Tiny and Marie had a great time together living in the country and it was while serving near Colchester that Tiny met her husband to be.

Bob (left) and an army colleague with their lorry

.

One day six of the Land Girls, including Tiny, were out hoeing in fields near Peldon when they heard a plane approaching. When they looked up they saw it was a Flying Fortress flying low, streaming smoke and obviously in a bad way. It finally ploughed into the ground a few fields away, so they all ran over

to see what had happened and whether they could help. It was all a terrible mess, but lying on the ground a few yards from the wreck was an airman who seemed to be just a mass of burns. They were sure they had to do something but couldn't think what. Eventually, in desperation, Tiny rushed off to the edge of the field and lifted the gate off its hinges â goodness knows where she got the strength from. Then between them they carried the gate over to the man, lifted him onto it, and then carried him a couple of miles across the fields to the nearest main road.

That was that. They never heard any more, whether he lived or died, went back home or whatever. In wartime you didn't hear these things, it was all âsecurity'. They didn't even know the man's name, only that he was an American airman. The sequel came almost exactly fifty years later. Somebody saw an item in one of the local papers about an American ex-pilot trying to trace the girls who had saved his life all those years before. Knowing Tiny's story they told her about it and, after much umming and aahing, she contacted the address given. The local paper had taken up the cause and after much checking and chasing managed to trace five of the girls, including Tiny. Eventually the airman, now a retired US Air Force Colonel living in Spokane, Washington, came over and they had a reunion which made the national press and television.

Mind you, I don't think Tiny will ever forgive him for his admiring tribute to âthe Butch girl who lifted the gate off its hinges!' That was her. [Editor's note: A couple of years later Tiny was informed by the US Embassy in London of his death â she was very touched that they should have remembered her].

Produce

(1940â5)

M

um could cook a good meat-and-two-veg meal, even if it was a right performance and a terrible ordeal for everybody around her, but for everything else she was a real âhit and miss' cook. The food could come out beautifully or it could be a disaster, there was no way of knowing in advance which it would be, and Mum didn't know either. One day in the war, though, when I called round to see her, she put on the table the most beautiful cake you had ever seen. It had the most perfect texture and yellow colour â it looked like a picture in a book.

âHave a piece,' she said, and set about cutting a great big slice. I just couldn't understand it. I mean, where could she have got the ingredients, especially the fat, because it was so tightly rationed? If you did manage to get enough fat together to make a cake you certainly didn't dish it out in big slices. There was something going on.

âWhere did you get the fat from?' I asked.

âJust have a piece and enjoy it,' she replied, âit's ever so good.'

âYes, but where did you get the fat from?' I repeated.

After another couple of rounds of this to-and-fro she finally said it was from the butcher. Well, that was no answer because fat from the butcher was on ration just like everything else, so there still had to be more to it. I kept on asking and asking, and refusing to take a slice of cake, until I got the truth. Eventually she

admitted that it was horse-fat, which accounted for the beautiful colour of the cake! Well, you know how horse fat is quite yellow. It seems that the butcher had managed to get hold of a supply and then found that he couldn't sell it. Even with the tight rationing nobody would buy horse-fat until Mum turned up and took the lot for a knock-down price. I am afraid that even for a knock-down price I still couldn't bring myself to eat horse so I never did taste the cake. I don't even know what happened to it and whether anybody else ate it.

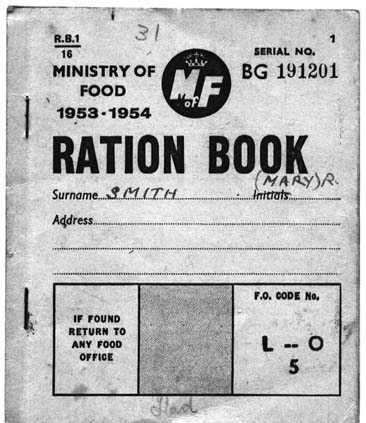

Polly's final ration book, kept just in case

â¦

These sorts of things seemed to happen to Mum. I remember that she was no good at making tea and somehow she never cracked the problem. Whenever she made tea it tasted awful and generally we used to avoid it, which suited her down to the ground because tea was expensive. Once, though, early in the war, I went round to see her and she was ever so insistent that I should have a cup of tea. I was suspicious and eventually got it out of her that she had got it cheap from âthat man up the road.' Well, âthat man up the road' was a real spiv. Goodness knows where he got his stuff from, but it must have been pinched. Everything he sold was ex-army and dirt cheap; he sold new army blankets for 4

s

at one time, I remember. Anyway, Mum had bought this tea from him and, because it was so cheap she had bought a load of it and was feeling generous. When I eventually gave in and said that I would have some tea she proudly went and got a packet out from the cupboard under the end of the dresser. She boiled the kettle, looking ever so smug, and made the tea. I was dreading it because, as I said, Mum couldn't make tea. In the event it was worse than you could have ever imagined in your worst dream â even Mum couldn't drink it! Unfortunately the taste was all too obvious and the reason all too clear. Mum had also bought a large quantity of cheap, almost certainly

ex-army (if the army had ever managed to get its hands on it, that is), carbolic soap and she had stacked the whole of this treasure trove together under the dresser. She tried separating them but it was no good because the damage had already been done. After a couple of weeks she had to throw all the tea away â a fine bargain that turned out to be.