Polly (17 page)

Authors: Jeff Smith

âYou're injured,' she said.

âNo I'm not,' I replied.

âYes you are,' she said.

And, sure enough, I had some sort of cut at the top of my nose and the blood was trickling down my face. I couldn't feel anything, I think because apart from the shock I was absolutely covered in plaster-dust and it was just soaking up the blood as it went. So she wrote a label, pinned it on me, and said I had to go to hospital. Then we had another performance because I said that I couldn't leave the baby, and it was quite clear that Fred couldn't look after him. Luckily Mrs Jones from a couple of doors along came up at that point and she took Robert.

Then I had to go and see Fred who, as controller, whistled up a car from nowhere and off I went to Forest Lane Hospital. This was a maternity hospital really, but in those days anybody would deal with anything. I suppose they had to. They cleaned up the wound very quickly and it turned out to be pretty trivial, but the doctor patted me on the tummy and asked when it was due. When I told him he decided that I would have to stay in for observation, so we had another performance while I told him about the other baby. Eventually he said I would have to take some pill or other, and then he would let me out if I promised to take it easy.

While I was waiting I got talking to this old lady who was waiting for transport. She had been injured but was a bit unhinged too, and truth be told had no idea what was going on. They had found somewhere for her to go and now she had to wait. Eventually my pill turned up, and I swear it was the size of a tennis ball. I have never been good at taking pills and goodness knows how many attempts it took before I finally got this one down. No sooner had I done so when a taxi arrived. I decided to be helpful, so I went and found the old lady and packed her into the taxi, then set out to walk back home. After about a hundred yards I heard all this shouting, and looked round to see the doctor and a couple of nurses running down the road after me. The taxi was for me, not the old lady.

When I got back there wasn't much to be done. The house was ruined and so dangerous that it would have to be pulled down as soon as possible. Fred was still organising the recovery crews who were, by now, salvaging whatever furniture could be saved and arranging for it to go into store. I was given a ticket for Salway School where there was an emergency shelter and arrangements for feeding those who had been bombed out. As I was leaving this soldier came running out of the ruins of the house and held out his hand.

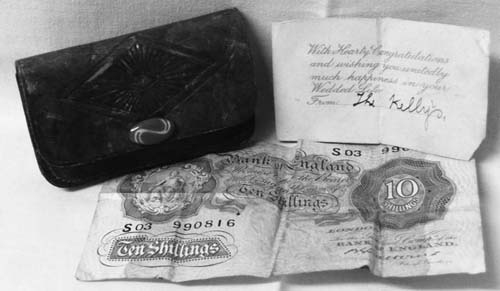

Mrs Kelly's purse and contents

.

âIs this yours, missus?' he asked.

He was holding the purse that Mrs Kelly had given us as a wedding present. It contained our 10

s

. 10

s

was a lot of money when Mrs Kelly had given it to us and we had decided to keep it for emergencies. In a real emergency it would have bought us a week's food, or paid the rent, or just tided us over. We got very close to using it once or twice in the early days, but never quite needed it. Whenever the design of notes was changed we substituted one of the new ones, but otherwise we hung onto it â and I have still got it complete with the little gift card from Mrs Kelly. It was still a lot of money even then and I have always remembered the honesty of that soldier â he could easily have kept that money and nobody would have ever been any the wiser. I suppose war brings out the best in some people, just like it brings out the worst in others.

Anyway, I arranged to go and stay with my sister in Buckhurst Hill and Fred arranged a car to take us there. My sister Jane was in the Land Army near Newmarket, and she found me a billet in a little hamlet nearby. That was how we'd met Aunty Blinco.

While we were away Fred found us half a requisitioned house in Earlham Grove, just round the corner from Keogh Road. We might have been safe in the country, but I didn't want to risk having my second baby with the primitive hospital system there, so when it was due I wanted to return to London.

Fred wasn't happy with the idea and tried to talk me out of it â he even sent me a letter listing all the incidents during a 3-day period but I still thought that London-with-bombs was safer than the Newmarket local hospitals (see chapter 18). By then the doodlebugs had finished, but we were getting rockets instead. They were worse because you got no warning and there was nothing you could do. One day I was walking down Earlham Grove with Robert in the pushchair and little Keith Lee walking beside me. He was a friend of Robert's and I had taken the pair of them shopping. As we crossed Sprowston Road we were suddenly lifted about 2ft off the ground â all three of us â and then put down again. Almost immediately there was an almighty explosion at the other end of Earlham Grove where the rocket fell. I have never heard anybody else talk about it, but I am sure there must have been some sort of air-wave or something as the rocket went past.

A mother and her child were killed in that incident. This woman and her husband were a bit strange, in fact I think that they were rather simple. Their son was an absolute horror and everybody used to avoid him and keep their kids away from him, but his parents loved him and they were such a happy little family. For some reason, though, the son and Robert really hit it off and they used to play together ever such a lot. An hour or so after the rocket landed I was standing at the door and saw the father walking down the road. He had been called at work and told of the deaths. As he walked down the road the tears were just rolling down his face â I can still see him and it still chokes me up to think about it.

At the very end of the war I was just coming out of Woolworths with Robert (and the baby in the pram) as a man was coming in. He looked at us and fainted! He was a manager in the sugar-boiling department at Clarnico when I used to work there and he lived nearby when we were in Keogh Road. Robert used to hang on the gate watching the world go by, so this man first used to say hello, then he talked to Robert, then used to give him a sweet, and eventually Robert asked if he could have a sweet for his Mum too, so he used to get two sweets. This man had thought that it was me and Robert who had been killed by the rocket â no wonder he fainted.

The other near-miss was the rocket that landed in the middle of Earlham Grove. We were away at the time and it only did minor damage to the house, including shaking most of the plaster off the living room wall. When Jane got married just after the war we covered the gap with a huge Union Jack. That rocket provided the site for Earlham Grove School.

Early Post-War

(1945â50)

I

t's funny to look back to just after the war and remember how rough it was, though at the time we thought that it was fine â I suppose because it was so different from the war. Really, anything was bound to be good when you weren't being bombed and didn't have to worry about who was going to get killed next. The council gave us half a requisitioned house in Earlham Grove. Goodness knows who had owned it before or how it came to be requisitioned but at the time you just didn't think about that sort of thing. It was one of those big Edwardian houses with big rooms and tall ceilings, and was built for an altogether more gracious age. It even had a coach house. Well, we called it the garage but it was meant for a horse and carriage. It was built onto the side of the house and had huge double doors to allow the carriage to go in and out but, of course, we only ever used the little wicket gate let into one corner of one of the big doors. It even had a hayloft, to keep food for the horse I suppose, but we never went up there. The house must have been built early in the century when that area of Forest Gate was the choice of wealthy Jews from the East End rag trade who moved out to be away from the squalor but in easy reach of their factories. There were still a lot of Jews living along there and next door the Bs still even had a maid. She was a leftover from the 1920s when the middle classes all had a live-in maid, but Annie (that was her name) had never moved on and became pretty well one of the family. Goodness knows

how old she was, but by then I think she needed more help from the family than she could ever give them.

Polly's two sons in the garden of Earlham Grove in about 1948.

The upstairs half of our house was given to Mr and Mrs J who had lived just along by us in Keogh Road. They had one son named Reggie who was a teenager by then. Mind you, in those days we had never heard of teenagers; you just grew up from being a child to being an adult. Anyway, we had the downstairs half, which had a front room, a large kitchen in the middle, and a back room which opened through a conservatory into the garden. Our half of the house included the cellar, with its huge old stone wash-boiler in one corner, heated by lighting a fire under it, and the loo in the opposite corner. It also had a separate front cellar, which was once used by the maid but was now just an odds and ends store of stuff from whoever used to live there before us. Upstairs we used the front room as the bedroom, with our double bed in the middle and the boys' beds in opposite corners on either side of us. The back room was rather grand and had obviously been the lounge, but it cost a fortune to heat

so it was usually very cold and we didn't use it much apart from high days and holidays. I remember that when we moved in the walls were covered in some awful smelling brown-stain that had obviously trickled down the wall. I think it must have been disinfectant or something. I suppose that says something about the state of the place before it was requisitioned but it didn't bother us â we were just pleased to get a roof over our heads. It took ages to scrub it all off though, and even then I could always smell it but nobody else did. Maybe it was just my imagination. Our George slept in that room for a while when he was first de-mobbed and before he got himself settled down. But to all intents and purposes we lived in the kitchen, with its huge dresser all along one wall, a big pine kitchen table in the middle and a couple of easy chairs beside the fire. We only lived there for a few years, but we had some happy times and I still think of that as our first real home, perhaps because that was the first place where we had both boys and the family was âcomplete'. It wasn't at all convenient and for baths we had to use a tin-bath in front of the fire â though heating water was such a pain we didn't use it very much (Fred used to take himself up to the Turkish Baths once a week).

Just after the war we still had rationing, but even when stuff was off-ration nothing was easy to come by and you had to make do. One year we decided to raise some chickens for eggs and meat and so we went down to the egg-and-chick shop in Angel Lane and bought some day-old chicks. You could actually buy day-old chicks from this shop â it had a wooden box display in the window heated by a light bulb and it was always full of little fluffy chicks. The boys used to be fascinated. Anyway, we bought these chicks and though some of them died pretty quickly we managed to raise a couple of them in the shed at the end of the garden. We didn't have much success with the eggs so we decided that it was time to try the meat but, of course, this meant we had to kill one of them and we realised for the first time that none of us quite knew how. Well, we knew how, but none of us had the confidence to actually do it without causing the poor creature to suffer. At last my brother Bob volunteered to wring its neck and then, of course, we were all full of advice about how it should be done â how you had to be firm and do it quickly and strongly. The eldest boy was always a bit soft-hearted about animals and had got quite attached to the chickens so we had to send him off on some errand or something and Bob went to get the chicken. He brought it down to the garage and stood there holding the poor blighter while we all watched. At last he said that he couldn't do it while we were watching so we all went inside and waited. Suddenly there was this awful cry of, âMary! Mary!' from the garage so we

all rushed out to see what could possibly have happened. And there was poor Bob, standing there as white as a sheet, holding the chicken's head in one hand while this headless chicken was running round and round his feet. He was absolutely stuck to the ground in terror and we were just as paralysed with laughing, until the poor thing fell down. Afterwards he told us that he was so concerned about not making the poor thing suffer that he had wound his arms round as far as he could with his hands round the chicken's neck and then untwisted them round as hard and as fast as he could, but so hard and fast that its head had come clean off! We just had time to clean up the mess and hide the evidence before the eldest boy got back and we told him that somebody had stolen the chicken. I don't know whether he ever put two and two together when we had chicken for dinner.