Polly (4 page)

Authors: Jeff Smith

Dad working in the market had other benefits. When I was ill once he came in to see me and asked if there was anything I wanted, some grapes or something. Well, I didn't want anything to eat, but I really wanted some flowers. I knew that posh grown-ups got flowers as presents and I wanted the same. It was early in the year, springtime, and blow me down if he didn't turn up from work that evening with a box â yes, a whole box â of daffodils. From that day I have always loved yellow flowers, especially daffodils. I suppose he got them cheap, if he paid for them at all, but he was always generous over that sort of thing. Our Bob had a friend who was run over and killed by a car. It was all dreadfully sad. Somehow in those days the communities seemed much closer together, and an accident like that touched everybody. Anyway, for the funeral

Dad got a whole box of chrysanths from the market. I thought it would be a good idea to keep some of them for the house â after all, nobody would notice a couple of bunches missing from a whole box. Mum was horrified at me, and completely adamant, âThose flowers was bought for Billy Hoskins and Billy Hoskins would have them â ALL!'

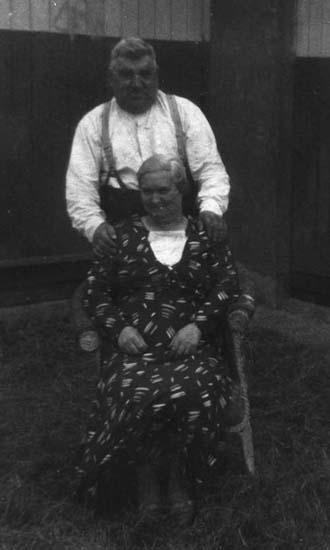

Mum and Dad on holiday in the late 1930s.

There was always great excitement when it snowed â not for us kids but among the unemployed men. They would all rush off straight down to the Council Offices and see if they could get taken on for snow clearing â it was about the only work that many of them could get. Those taken on would be given their streets and go out to spend the day shovelling snow. You have to remember that they were dreadfully poor, most of them couldn't afford any proper warm clothes. Can you imagine shovelling snow all day wearing a vest, jacket and scarf, thin trousers, no socks but only a pair of thin shoes (maybe with holes in) on your feet and no gloves on your hands?

Mum was always generous to these poor devils. She used to keep an eye on the street from the front bedroom window and would give them a hot drink when they got as far as our house. We had the top half of the house and the stairs led straight down to the front door. One day Mum went downstairs to talk to a snow clearer and after a couple of moments came back upstairs, made a mug of cocoa and sandwich and went back down. I stood in the kitchen doorway to watch what was going on but she shouted at me to shut the door and keep the warmth in. I was being nosey, though, so I went out onto the landing and shut the door behind me. That way I could stand in the shadow and still watch what was going on at the front door. I don't know whether Mum knew I was there or could still see me, but I thought that I was hiding. Anyway, she gave this man the cocoa and sandwich and he came in and sat on the foot of the stairs. He was shivering like nobody I had ever seen, or have ever seen since, I think. At first, he could barely get the sandwich into his mouth because he couldn't control his teeth. Anyway, Mum stayed talking to him until he finished the food and got up to leave. The poor bloke didn't seem to know enough ways of saying âthank you', and I suddenly realised that he was actually bowing to MY MUM!

âThanks lady,' he said one more time, âyou saved my life.' I think he meant it.

Jobs were impossible to find and men would do anything for the chance of work. There was a woodyard at the far end of the street, Glikstens I think it was. They had a couple of vacancies, nothing special â just a couple of men to work in the yard fetching and carrying. Normally these sort of jobs were snapped up as soon as they became available by somebody telling somebody as soon as anything was known. This time, though, they wanted to do it âproperly' and so they were stupid enough to advertise the jobs in the local paper, telling candidates to present themselves for interview on a certain date. Well, late in the afternoon of the day before that, a steady procession of men started going past our front door. One of them sat on our front wall for a rest and so

Mum gave him a cup of tea. We could barely understand what he said in reply because his accent was so thick. It turned out that he had walked, yes walked, from Newcastle-upon-Tyne to try for this job. From then on Mum stood at the front door, pretty well until bedtime, giving out cups of tea to anybody who asked. We kids ran up and downstairs with empty cups, washing up, fetching more milk and whatever. We were absolutely forbidden to go outside, though. By the time we got up next morning there were more people than I had ever seen in the street. Apparently Glikstens were horrified by the size of the crowd, and anyway they had no way of dealing with so many applicants, so they put a notice on the gate to say that they didn't have any vacancies after all. The result was disaster. Well, you can imagine, such a huge crowd of desperate men, some of them had walked the length of the country, along with all those who had been queueing since the day before and through the night. There was a riot, no other word for it. In the end the men broke into the yard and set light to it. I don't know whether it was an accident or deliberate, but the result was the same. Of course, the fire engines took ages to get through the crowds who were not feeling very cooperative anyway. By the time they got there the yard was ablaze from end to end and there was nothing to be done. It burned right through the night and well into the next day before they got it under control.

The police were called and had to quell the riot and control the crowd. Mum had sent me up to Stratford on some errand and when I got back there was a rope barrier across the end of Lett Road. I didn't think about it and ducked under the rope to go home. Suddenly this policeman called out and came chasing after me. I was dead scared, but when I explained I lived there he got another policeman to walk all the way home with me. A little while later there was a man sitting on our front wall, so Mum went to see what he was up to and send him on his way. Instead she took pity and asked if he would like a cup of cocoa. I will always remember his reply â âI'd even like a glass of water, lady.'

He must have been in a bad way because Mum invited him in to sit on the bottom of our stairs while she got the cocoa. Then she noticed his feet. He had the remains of a pair of boots wrapped round them, and inside those were some tatters of an old pair of cotton socks stuck to his feet by the dried blood. So she sent me to boil a kettle, then bring a bowl of hot water, then bring a flannel, then bring scissors to cut off the remains of the socks, then bring a towel. Mum was soft-hearted but never did anything herself â she supervised while others did all the fetching and carrying! To crown it all, she even dug out an old pair of Dad's socks and an old pair of boots before she sent him on his way. Dad hit the roof when he got home.

Over the next day or so the men gradually drifted away and the street became quiet again. I will never forget the desperation of those men that brought them from the other end of the country to start a riot in our street.

A Woman on the Bus

(1916)

O

ne day, a couple of years after the war [Editor’s note: Second World War], I was upstairs on the bus and started talking to this woman who happened to be sitting next to me. Goodness knows who she was, I’d never seen her before or since, but she was about the same age as me and grew up in the same places as me, so we had a lot of experiences in common. We were talking about how things used to be, how tough our early lives had been, how grim life had been in the First World War, the Depression, and so on and on, when we passed the City of London Cemetery. The woman looked straight past me at the cemetery and went all misty-eyed. For a couple of moments she sat silently watching the cemetery going past. Suddenly she said, ‘My baby brother is buried in there.’ Well, it wasn’t unusual for little babies to die back then; we didn’t have the medical services to care for babies either during the birth or if they got little colds or other illnesses afterwards. As often as not you couldn’t afford to get a doctor anyway, unless things were really bad, and then it was often too late. Even so, it didn’t make any difference that baby deaths happened so often – they were never any easier to cope with.

Her brother’s death had obviously affected this woman terribly and so I made some comforting noises about how awful it must have been, and how difficult it used to be for everybody, how babies used to die because we could not afford doctors, and so on, when she broke in, ‘It wasn’t like that!’ And

what a story she went on to tell! She admitted that most of her story had been put together afterwards, because at the time she was too young to realise quite what was going on. Her mother had never said anything about it and had refused to talk about it, so she had gradually made sense of the events she remembered as she grew up and her understanding increased.

Her mother had been pretty young, barely much of a teenager herself, and it seems that she had met this fellow who had a good job and in a matter of months they were married. They moved into a couple of rooms, which was good going when lots of just-marrieds had to live with one or other set of parents. Nine months later the first child was born – the woman that I was talking to. Within a very short time the First World War broke out and the woman’s father joined up. So, within little more than a year, this woman’s mother had met a man, married him, had his child and he was gone again. Looking back, it was clear that she had no idea at all how to cope with her life, though thankfully she still had her mother’s support.

Anyway, over the next couple of years they had quite a struggle to get by. She thought her father visited once or twice, he must have got leave sometimes, but she wasn’t completely sure. Then she gradually became aware that something was up. Her mother wasn’t very well, was beginning to get fat and there were all sorts of whispered conversations. She could see that her mother was dreadfully upset and she stopped going out. Instead her grandmother used to get all the shopping and she came round for long conversations, sometimes arguments. Her face was always cross and she barely spoke to her granddaughter. Eventually, her mother sat her down to tell her a ‘very important secret’. She was told it was terribly, terribly secret and that she must never tell anyone – not even her father! She was going to have a little brother or sister, but no one must ever know. She could not understand how nobody was ever to know, especially her father when he came home again, but she accepted what her mother had said. Her grandmother kept coming round and doing all the jobs that meant going out, but kept just as stony-faced as ever.

Eventually the day came; her mother kept getting pains and took to her bed. The daughter, even though she was only a couple of years old, could see that there was something wrong and wanted to get help, but her mother said not to worry, grandma would soon be there. Eventually grandma turned up, went in to see the mother, came out again and set about collecting ‘things’ together. She told the little girl to play, to be an especially good girl, and not to go into the bedroom. The grandma stayed much later than usual, in fact right into the night. At bedtime grandma put her to bed on two chairs in the living room. She

didn’t sleep very well and kept hearing shouts and yells from her mother, sobs, grandma’s hardest voice, and eventually a baby’s cries.

Her grandma was still there next morning when she woke up. Grandma made some breakfast and told the girl that every thing was alright and that her mother would just need a couple of days’ rest.

‘What about my little brother?’ she asked (she said that she ‘just knew’ it would be a little boy), but grandma just said something about not being a time for silly questions and she should eat her breakfast. And that was that. For the next couple of days grandma was there for almost the whole time. The girl went in to see her mother a couple of times but she looked perfectly well enough to a three-year-old. Then her mother got up and grandma went home. The girl kept asking about her baby brother, but only ever got answers to completely different questions.

The day after her mother got up for the first time she woke her daughter very early and said they were going for a walk. They were going to take her baby brother out – and this was the first and only time the baby was mentioned – but it was all still ‘a great secret’. Her mother said that she would have the special job of looking after her brother, but still she must not tell anybody about it. After a quick breakfast her mother dressed her up very warmly – it was winter – and put her in the pushchair. Her mother then tucked a very tight bundle in beside her, and somehow she realised this was her brother but couldn’t understand why she could not see his face. Her mother then wrapped and tucked her and the bundle into the pushchair with two or three blankets. She had never been so tightly wrapped in and could barely move. With one more warning about ‘the secret’ they went out. It was very early, in fact it was still dark and there weren’t many people about. They, or rather, her mother, walked for miles and after a while it began to get light. It was a cold, drizzly, dreary, morning but her mother didn’t seem to notice and just pushed on as fast as she could walk. They were walking up a long, tree-lined, street when a lorry went past them and then stopped a few yards ahead. There were a lot of soldiers in the back and they started calling out to them.