Pompeii (21 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

The upper-floor apartments,

cenacula

, were accessed through stairways from the street at numbers 18, 19, 6, 8 and 10a. The description

equestria

refers literally to the Roman elite class of ‘knights’ (or ‘equestrians’), a wealthy group who would expect to live in rather grander circumstances than this. Here the adjective is probably used as a promise (or an expectation) of some social respectability, as in the old phrase ‘

gentleman’s

outfitter’. The houses (

domus

) were most likely the ground floor apartments, numbers 7, 9 and 10, unless the atrium house in the centre was also up to rent, Nigidius Maius himself having moved elsewhere.

It is hard to know exactly where on the social spectrum of the town’s population to place the occupants of these various units, though various remarks in Petronius’

Satyrica

confirm the relative ranking of prestige implied by the material remains. At one point, in the middle of a marital row, Trimalchio takes a barbed potshot at his wife’s lowly origins: ‘if you’re borne on a mezzanine, you don’t sleep in a house.’ Elsewhere, the social rise of one of Trimalchio’s guests is marked by the fact that he is subletting his

cenaculum

(‘from the 1 July’, interestingly the same date as Nigidius Maius’ contracts began) because he has bought a

domus

. Nor can we be certain about the length of these leases, and so about the security of tenure enjoyed by the tenants. But another rental notice in the town, referring to accommodation in the Estate of Julia Felix, advertises ‘an elegant bath suite for prestige clients,

tabernae,

mezzanine lodgings [

pergulae

] and upper-floor apartments [

cenacula

] on a five year contract’.

What is clear, however, is that the

insula

Arriana Polliana nicely captures in a single block the varieties of housing available in the city. We can only now pity the poor

pergula

dwellers, constantly faced with the comparatively palatial expanses of the atrium house next door.

But it was not only the poorer Pompeians who lived in different kinds of accommodation. Not all the wealthier inhabitants of the town lived in the ‘standard’ Pompeian atrium house. There are some houses, for example, which in the last phases of the city’s history – while retaining some of the basic elements that we have already seen – have garden areas so developed and expanded that the whole focus and the character of the property seems completely altered.

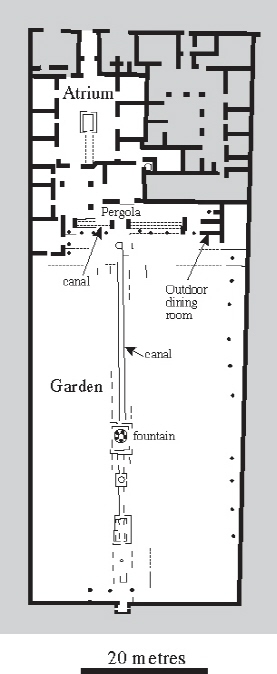

A classic case of this is the House of Octavius Quartio (so called after the name on a signet ring found in one of the shops there), which was being renovated at the time of the eruption. As the plan shows (Fig. 9), the house buildings themselves were not particularly spacious, but the focus of attention was on the large garden, and its elaborate decorations and water features (exploiting the mains water supply). Along the garden front of the house stretched a long pergola, covering a narrow course of water, crossed by a bridge and originally lined with statues. At one end was an outdoor dining room, at the other an ornamental ‘shrine’, which once held an image of the goddess Diana or Isis (the surviving paintings here include Diana bathing and a priest of Isis). At a lower level, another narrow waterway stretched some 50 metres down the length of the garden, spanned by bridges and arches, with elaborate fountains at one end and in the middle, and paintings decorating almost all possible surfaces. The garden on either side was planted with walkways of shrubs and trees, as well as more pergolas. The water itself doubled as ornamental pool and fish farm (Ill. 39).

The influence behind many of these features is the architecture of the out-of-town Roman house, or ‘villa’. Characteristic elements of the villa garden were ornamental watercourses, shrines and walkways between flowers and trees. Cicero on one occasion mocked the shamelessly aggrandising titles given to their garden canals by the Roman elite: ‘Nile’ or ‘Euripus’ (after the stretch of water between the island of Euboea and the Greek mainland). But he was, nonetheless, very keen on a Euripus in one of his brother Quintus’ country properties, and at one stage he had it in mind to build himself a shrine to the obscure goddess Amalthea, in imitation of an elegant feature in his friend Atticus’ villa garden. Later the emperor Hadrian was to install a very flashy ‘Canopus’ (another Egyptian waterway), which still survives, in his rural palace at Tivoli. Also the mark of a villa garden was the combination of productivity and ornament that we find in this particular pool/fishpond. For the Roman proprietor, part of the pleasure of his country estate was the way productive farming might be integrated into its decorative scheme: a meeting of agriculture and elegance.

Figure 9

. House of Octavius Quartio. A relatively small site, and even so the ornamental garden in this house vastly outstrips the small area of the building itself. The shaded portions are parts of different properties.

This design, then, brings the style of the out-of-town property into the city itself. It is very successful with modern visitors to the site, who love wandering along the waterways and under the pergolas, just as the ancient residents must have done. Some archaeologists, however, have been rather sniffy about it. There is too much, they argue, crammed into too small a space (‘two people cannot walk next to each other under the pergola without running up against a fountain, little bridge, pillar, or post at every turn, or tripping over the statuettes in the grass’). This is a ‘Walt Disney world’, in which an owner with little taste has tried to imitate the leisured country world of his betters, consistently choosing quantity over quality.

39. The view down the long garden of the House of Octavius Quartio. An elegant series of pools and pergolas – in a jewel-like miniature design? Or is this a scheme completely out of scale to the site, a classic case of

nouveau riche

pretensions going wrong? Archaeologists are divided on the question.

It is right to face the fact that ancient art and design can be decidedly secondrate. And some of the paintings in this house are ‘of modest quality’, to put it politely. Yet it is hard not to suspect that in finding the house ‘tasteless’, we are – albeit unconsciously – sharing the prejudices of many elite Romans, who were ready to scoff at palatial schemes brought down to an ordinary domestic scale. After all, Trimalchio, the ex-slave may have been horribly vulgar. But part of the joke of Petronius’ novel is that he is aping the culture of the aristocratic elite all too well. In laughing at him, we find we are laughing at them (or at ourselves) too.

No one has ever been sniffy in that way about the group of houses on the western edge of the city, built directly over the old city wall in the early years of the Roman colony (after 80 BCE, perhaps by some of the original colonists) – and in their final form dramatically dropping down the slope towards the sea, in up to four or five storeys (Ill. 15). These are now, in many ways, the most impressive properties in all of Pompeii, partly because to walk around them on their different levels, up and down their surviving staircases, gives a feeling of being

right inside

an ancient house that you rarely get elsewhere.

They are also one of the saddest stories of the modern excavations. Bombed in 1943, they were excavated in the 1960s but have never been properly published and even the unpublished records and notebooks are often skeletal. This means that we have little idea of the history of their development or of some of the details of their internal layout. It is hard in places to work out where the divisions between the houses fall, or how many living units there were in all. They are also not open to the public (although you can get a good view of them from the main entrance to the site at the Marine Gate). The result of all this is that, although they are a fondly remembered highlight of the site for those who have been lucky enough to get permission to visit them, they have not often made much of an impact in guidebooks, general histories of the town or even student courses. They have not affected our view of Pompeian houses as much as they should have done.

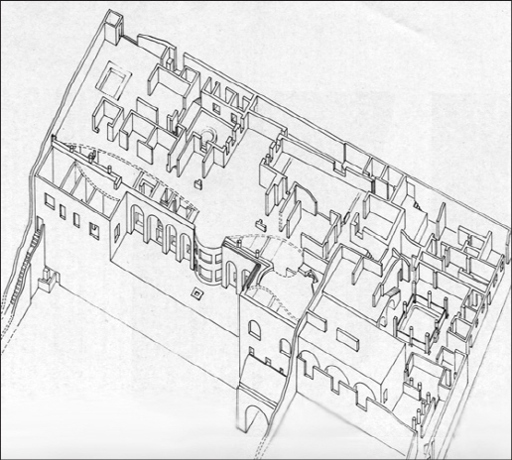

The best way of understanding these large, multi-layered properties is to think of them as atrium houses organised along Vitruvius’ principles, but vertically rather than horizontally, and facing the view over the sea rather than turned in on themselves. In the very grandest of these, the House of Fabius Rufus (named after a man whose name appears in several graffiti in the house), you enter from the ground level on the city side, into a relatively modest atrium for an establishment of this size. But instead of moving on through the house to the ‘exclusive’ areas, you move downstairs to two further levels where on the sea side there is a series of lavish entertainment suites with large windows and in places terraces outside. The service areas seem to be in dark quarters, set back into the hillside, with no view and precious little natural light (Ill. 40).

40. The House of Fabius Rufus. This axionometric reconstruction gives an idea of the complexity of this multi-level design. The show rooms look over the sea. The service quarters are tucked behind in the hillside, dark and gloomy as usual.

For the owners and the favoured invited guests, this was a place to enjoy the light, the air and the vista. A graffiti artist, at work on a stairway within the house, got the point. Amidst the scrawlings of one Epaphroditus, who has scratched his name several times, plus his girlfriend (‘Epaphroditus and Thalia’), and just under a lover’s rhyme that was enough of a cliché to be found written up several times across the town (‘I wish I could be a ring on your finger for an hour, no more ...’), someone has inscribed the first three words of the second book of Lucretius’ philosophical poem

On the Nature of Things

: ‘

Suave mari magno

’ – ‘Pleasant it is, when on the wide sea ...’ This continues, as our scribbler presumably knew, ‘... the winds stir up the waters, to gaze from dry land at the great troubles of another.’

Pleasant indeed it must have been to gaze out to sea from the House of Fabius Rufus.

Names and addresses

At the doorway of a small house in the south of the city, most of which behind the entrance still remains unexcavated, a small bronze plaque was found. It reads: ‘Lucius Satrius Rufus, imperial secretary (retired)’. If it is, as seems plausible, the name plaque from the door, then it is the only such marker so far known in the city. Here lived a man who was a member of, or at least connected to, one of the oldest families in Pompeii. His exact geneaology is uncertain because ex-slaves and their descendants took the family name of their masters, so a Satrius might be one of this local line of notables, or might trace his ancestry back to one of their slaves. In this case, given the apparent size of the house and the nature of his job, we might suspect the latter. But whichever is the case, it looks as if we are dealing with a local man, who worked in the administration of the imperial palace in Rome, retired to his home city. There he proudly boasted on his doorplate of his employment in the emperor’s service.