Pompeii (45 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

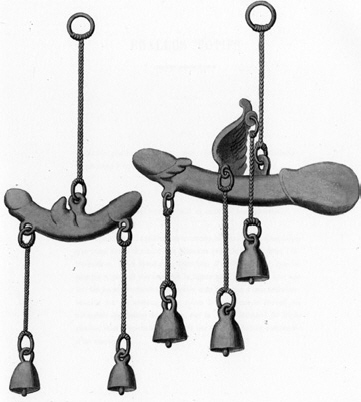

This is one of the most puzzling, if not disconcerting, aspects of Pompeii for modern visitors. In earlier generations scholars reacted by removing many of these objects from public view, putting them in the ‘Secret Cabinet’ of the museum at Naples or otherwise under wraps. (When I first visited the site in the 1970s, the phallic figure at the entrance to the House of the Vettii was covered up, only to be revealed on request.) More recently the fashion has been to deflect attention from their sexuality by referring to them as ‘magical’, ‘apotropaic’ or ‘averters of the evil eye’. But sexual they cannot avoid being. There are phalluses greeting you in doorways, phalluses above bread ovens, phalluses carved into the surface of the street and plenty more phalluses with bells on – and wings (Ill. 81). One of the most imaginative creations, which once jingled in the Pompeian breeze, is the lusty phallus-bird, a combination (I guess) of a joke and an unashamed celebration of the essential ingredient of manhood.

In this world, the main functions of respectable, well-off married women – that is, the occupants of the larger houses at Pompeii – were twofold: first the dangerous job of bearing children (childbirth was a big killer in ancient Rome, as it was in every period up to the modern era); and second the management of house and household. One tombstone from Rome famously hits the nail on the head. It is a epitaph put up by a husband to his wife Claudia. It praises her beauty, her conversation, her elegance; but the bottom line is that ‘She bore two sons ... she kept the house, she made wool.’ The lives of poorer women might in practice have been more varied – whether as shopkeeper, landlady or moneylender – but I doubt that the underlying assumptions about their role were very much different. This was not a society where women were in control of their lives, their destinies or their sexualities. The stories told by Roman poets and historians of racy, licentious and apparently ‘liberated’ women of the capital are part fantasy, part applicable only to such truly exceptional characters as those in the imperial house itself. The empress Livia was not a typical Roman woman.

81. The ‘phallus bird’ was one of the Roman world’s most extraordinary mythical creatures. Impressive, powerful – or just silly?

For elite men, the basic message was that sexual penetration correlated with pleasure and power. Sexual partners might be of either sex. There was plenty of male-with-male sexual activity in the Roman world, but only the very faintest hints that ‘homosexuality’ was seen as an exclusive sexual preference, let alone lifestyle choice. Unless they died too young, all Roman men married. Sexual fidelity to a wife was not prized or even particularly admired. In the search for pleasure, the wives, daughters and sons of other elite men were off-limits (and crossing that boundary might be heavily punished by law). The bodies of slaves and, up to a point, of social inferiors, both men and women, were there for the taking. It was not simply that no one minded if a man slept with his slave. That was, in part at least, what slaves were

for

. Poorer citizens, with a less-ready supply of servile sexual labour, would no doubt use prostitutes instead. As with dining, the rich provided for themselves ‘in-house’, while the poor looked outside.

Not that this made for a carefree sexual paradise, even for the men. As in most aggressively phallic cultures, the power of the phallus goes hand in hand with anxieties – whether about the sexual fidelity of one’s wife (and so the paternity of one ’s children) or about one’s own capacity to live up to the masculine ideal. In Rome itself, insinuations that a man had played the part of a woman, that he had been penetrated by another man, could be enough to blight a political career. In fact, many of the insults that scholars have sometimes taken as signs of Roman disapproval of homosexuality as such are directed only at those whose played the passive part. And, to return to Pompeii, whatever other associations that tiny bronze pygmy might have had, caught for ever in the act of attacking his own giant penis, it surely exposes some kind of sexual unease. Funny, fantastic, carnivalesque, it may have been. But it is hard to escape a more uncomfortable message too.

Nor is it the case that individual relations between Roman men and women were as unnuanced and mechanical as my stark summary might suggest. All kinds of relationships of care and tenderness flourished, whether between husband and wife, master and slave, lover and beloved. A expensive gold bracelet, for example, found on the body of a woman at a settlement just outside Pompeii is inscribed with the words ‘From the master to his slave girl’. It reminds us that affection can exist even within these structures of exploitation (though how far that affection was reciprocated by the ‘slave girl’ concerned, we of course do not know). And the walls of Pompeii, both inside and out, carry plenty of vivid testimony to passion, jealousy and heartbreak with which it is hard for us not to identify, even if anachronistically: ‘Marcellus loves Praestina and she doesn’t give a damn’, ‘Restitutus has cheated on lots of girls’. All the same, the basic structure of Roman sexual relations was a fairly brutal one, and not one that was female-friendly.

Within this context prostitution had a place both on the streets (or in the brothel) and in the Roman imagination. For the Roman government, prostitution could be a source of revenue. The emperor Caligula, for example, is said to have imposed a tax on prostitutes – though how exactly it was levied, where it was applied and how long it remained in force is anyone’s guess. Revenue apart, the main concern of the authorities was not to police the day-to-day activities of prostitutes but to draw a firm line between them and ‘respectable’ citizens, especially the wives of the Roman elite. Prostitution belonged to a motley group of occupations (including gladiators and actors) that were officially judged

infamis

or ‘disgraceful’, a stigma which carried with it certain legal disadvantages. Some prostitutes would anyway be slaves, but even those who were free citizens did not, for example, enjoy the protection against corporal punishment that usually went with Roman citizenship. Pimps and male prostitutes (who were, by the logic of Roman sexuality, effectively female) could not stand for public office. Tradition even had it that women prostitutes were not allowed to wear standard women’s clothes, but dressed in a man’s toga. This was a crossing of gender boundaries that firmly distinguished them from their respectable counterparts.

Prostitutes loomed perhaps even larger in the Roman imagination than in reality, from images of ‘happy hookers’ to the tragic victims of abduction sold off for sexual labour or the objects of public abomination or derision. In Roman stage comedies of the third and second centuries BCE, prostitution is a major theme. One of the characteristic romantic plots of these plays concerns the young man of good family who has fallen in love with a slave prostitute, controlled by a malevolent pimp. Despite their love, marriage is impossible, even if the young man could raise the money to buy her, because his father would not countenance such a wife for his son. But there is a happy ending. For it turns out that the object of his desire was actually a respectable girl all along: she had been the victim of a kidnapping and sold to the pimp; so she was not a ‘real’ prostitute after all. In comedy, at least, we are allowed to glimpse the awkward truth that the boundary between respectability and prostitution might not be quite so clear as we thought.

It is against this background that archaeologists have tried to pinpoint the prostitutes of Pompeii, and to identify the physical remains of the brothels. The total number they come up with depends entirely on the criteria they choose to adopt. For some the presence of erotic paintings can be enough to indicate a place for commercial sex. So, on this interpretation, a small room near the kitchen of the House of the Vettii, decorated with three paintings of a couple, man and woman, making love on a bed, is a dedicated place of prostitution – a moneyspinning sideline for the owners (or for their cook). It can be linked for good measure to a tiny scratched graffito in the front porch of the house which may offer the services of ‘Eutychis’ for 2

asses

. Alternatively, of course, the room has just been decorated in this way to please a favourite cook (whose lodgings, next to the kitchen, it may well have been), and the scrawled information (or insult) about Eutychis is nothing to do with it at all.

Others place the qualifying standard for a brothel rather higher. One scholar lists three conditions that more reliably indicate that we are dealing with a place primarily used for sex for profit: a masonry bed in a small room easily accessible to the public; paintings with explicitly sexual scenes; and a cluster of graffiti of the ‘I fucked here’ type. Needless to say, if you require all of these conditions to be met, the number of brothels in the town goes down – to one. On this argument, the upstairs or backrooms of bars might well have provided a place where some people sometimes paid for sex, but that is different from a brothel, in the strict sense of the word.

There are all kinds of traps for the archaeologist here. We have already noted the difficulties in interpreting the erotic graffiti and in deciding if the plain single rooms with masonry beds and doors directly from the streets were places of prostitution or just very small lodgings for the poor (why, after all, must we imagine that stone beds were particularly suited to prostitution?). But the key question concerns the difference between the dedicated brothel and any of the many other places in the town where sex and money were not kept entirely separate.

We have probably been rather too easily taken in by the Romans’ own attempts to insist that prostitutes were a clearly separate class of women (or men) and by the institutional image of the brothel and pimp given by Roman comedy. Most of the ‘prostitutes’ in Pompeii were probably the barmaids or the landladies (or the flower-sellers, or the pig-keepers, or the weavers for that matter) who sometimes slept with customers after closing-time, sometimes for money, sometimes on the premises, sometimes not. I very much doubt that many of them really wore togas (a classic piece of Roman elite male myth-making), thought of themselves as prostitutes or defined their place of work as a brothel – any more than the modern massage parlour is a brothel, or a hotel where, if you ask, you can rent a room by the hour. The search for the Pompeian brothel is, in other words, a category mistake. Sex for money was almost as diffused through the town as eating, drinking or sleeping.

Except in one case: a building five minutes’ walk east of the Forum, just behind the Stabian Baths, which meets all of the toughest criteria there have been for such an identification. It has five small cells, each with its own built-in bed and a series of explicitly erotic paintings, showing couples making love in a variety of different positions (Ill. 82). It still contains almost 150 graffiti, including a good number of the ‘I fucked here’ type (though not all are of that kind: one person at least was moved to scratch a quotation from Virgil). It is a rather dark and dingy place. Set on a corner, it has a door onto both streets (Fig. 17). What is now the main entrance in the one-way system used to cope with the crowds of tourists was probably the main entrance in antiquity too. If you enter this way you find yourself in a wide corridor, with three cubicles on the right and two on the left. At the end of the corridor, a masonry screen blocks the view of what lies beyond. That turns out to be the latrine – so clearly some care had been taken to ensure privacy for toilet-users, or alternatively to ensure that incoming clients were not greeted by the sight of another customer on the toilet.

82. This image of love-making from the brothel is set in more luxurious surroundings than the brothel itself seems to have offered. The bed is comfortably appointed, with a thick pillow. Next to it, on the left, stands a lamp, a hint that we are to imagine that the scene is set at night time.

The walls are mostly painted white, in what had been a relatively recent redecoration before the eruption (the imprint of a coin of 72 CE has been found in the plaster). High up above the level of the entrance to the cubicles are the erotic paintings, which show men making love to women from behind, underneath, on top, and so on. There are just two significant variants. One painting shows a single male figure with not just one, but two large erect phalluses (on the ‘two is better than one’ principle, presumably); another shows a man on a bed and a woman standing by his side, not engaging in lovemaking, but looking at some kind of tablet – perhaps meant to be, in a nice self-referential joke, an erotic painting.