Pompeii (47 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

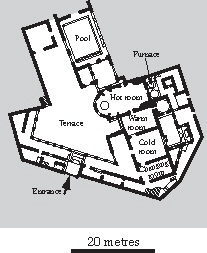

Key

a entrance to men’s bathing suite

b men’s changing room

c warm room

d hot room

e furnace

f hot room

g warm room

h women’s changing room

i plunge pool

j swimming pool

k shops

Figure 18

. The Stabian Baths

The Stabian Baths were the oldest in the city, going back long before the Roman colony. The different phases of their construction are very complicated to disentangle (and not helped by the fact that the notes of one major study of the fabric were destroyed in the bombing of Dresden in the Second World War). The very first building on the site, which some archaeologists have dated as early as the fifth century BCE, took the form of an exercise court (

palaestra

) and a row of ‘hip baths’ in the Greek style. But the baths as we see them now were the result of a major redevelopment in the middle of the second century, with a series of improvements and refurbishments going on right up to the end of the city’s life, including the provision of water direct from the aqueduct, rather than from the earlier well (Ill. 83). We assume that they were publicly owned and administered, not only because of their size (it is hard to imagine a complex this large being private enterprise), but also thanks to inscriptions which record the investment of public money: the sundial, with its Oscan text noting that it was set up with the proceeds of the fines; and building of the

laconicum

and

destrictarium

by

duoviri

in the first century BCE, ‘out of the money’, as the inscription states, ‘which they were legally obliged to spend either on games or on a monument’.

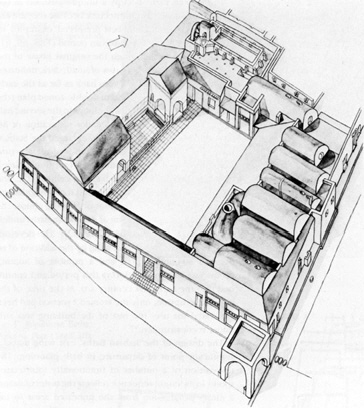

83. The Stabian Baths. In the centre of this reconstruction drawing is the open exercise area. On the right are the vaulted rooms which form the men’s and women’s bathing suites. The Via dell’ Abbondanza runs along the front face of the complex (bottom left) – with the large arch, associated with the family of Marcus Holconius Rufus.

The main entrance was from the Via dell’Abbondanza, just near the statue of Marcus Holconius Rufus, where the street widens to form a little piazza. A row of shops fronted the street itself, but going through the vestibule you came into a colonnaded courtyard, which was the exercise (and sitting) area. At some point money may have changed hands. For while some public baths made no charge, others levied a small fee. We do not know which was the case here, but the easiest place to have taken any cash would have been at the entrance to the main bath suite at (

a

).

The layout of the bathing rooms themselves is extremely practical. In the Stabian Baths the heating is provided by a single wood-burning furnace, which was connected to the underfloor heating system or ‘hypocaust’. The earliest example of this system to survive in the Roman world (it was probably invented in Campania), this provided a much more powerful way of heating the rooms than the earlier system of braziers, which was still in use at the Forum Baths (Ill. 84). The basic principle was that the floors of the rooms to be heated were raised on small pillars of tile, so providing an air space underneath. This was warmed by the heat of the fire – the nearer to the furnace each room was, the hotter it would become. The arrangement in the Stabian Baths allows two sets of room to be heated on either side of the fire: two very hot rooms, (

d

) and the smaller (

f

), and two warm rooms, (

c

) and the smaller (

g

).

Why two sets? The smaller set was for women, whose bathing was here segregated from the men’s. They did not use the impressive main entrance to the baths on the Via dell’Abbondanza, but entered up a side street through a door, which is said to have carried the painted sign ‘Women’ (visible soon after the original excavations, it is now completely illegible). Instead of emerging into an airy courtyard, they had to make their way down a long, poky corridor before they reached a place they could perhaps pay to leave their clothes (

h

) and enter their own smaller suite of rooms. This was the arrangement at the Forum Baths too, where there was a second less elaborate series of female bathing rooms. In the Central Baths, no such separate provision was planned: either women would have been excluded, or they would have bathed at separate times, or it would have been that red rag to ancient moralists – mixed bathing.

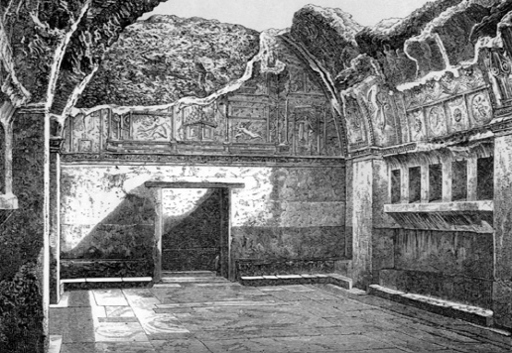

For the men visiting the Stabian Baths, the choices would have been many. They left their clothes in the changing room, (

b

), a beautifully stuccoed room, where the individual niches for the bathers’ belongings still survive (Ill. 85). We may guess that the establishment’s staff included a guard for this facility, but Roman writers tell many tales of petty thieving at the baths. Maybe it was better to leave your valuables at home. They could then move outside for all kinds of games and exercise. There was a swimming pool, (

j

), and, if the discovery of a couple of stone balls is significant, perhaps a place where you could play some form of bowls. The oiling and scraping that traditionally went with Roman exercise may have been provided by the visitor’s own slaves (brought with him for the purpose), or on a Hadrianic self-help basis. But there may have been staff at the baths for this too – though where the ‘scraping down room’ built by the

duoviri

was, we do not know. Inside the bath-suite itself, there was the possibility to sweat in the heat, to sit around in the small pools (rather like a modern hot tub), or to plunge into the cold bath, (

i

) – which is reckoned to be a later conversion of the earlier

laconicum

.

For those who lived in small dingy houses, or perched over their workshop, these baths must have been a real People’s Palace (Plate 16). Not only were they marvellously spacious, with all the pleasures of swimming and splashing and whatever kind of exercising took your fancy, but they were decorated in lavish style. The barrel vaults of the bathing suite were painted in rich colours, while the sun streamed in dramatically through roundels in the ceilings. Where the sun did not stream, the rooms were kept brightly twinkling with a battery of lamps. In one corridor of the Forum Baths a store of 500 lamps was discovered.

84. Bronze brazier from the Forum Baths, carrying a characteristic Pompeian visual pun. It was a gift to the Baths from a man called Marcus Nigidius Vaccula. ‘Vaccula’ means ‘cow’ – and so he emblazoned a cow as an emblem on this piece of metalwork.

It is not only the modern visitor who is drawn to reflect on quite how hygienic it all was. There was no chlorination in the pools to mitigate the effects of the urine and other less sterile bodily detritus. Nor was the water in the various pools constantly and quickly replaced, even if there was sometimes an attempt to introduce a steady flow of new water into them, which would at least have diluted the filth. The hot tubs in the bathing suite itself must have been a seething mass of bacteria (just as many eighteenth-century European spas). Martial jokes about the faeces that ended up in them, and the Roman medical writer Celsus offers the sensible advice not to go to the baths with a fresh wound (‘it normally leads to gangrene’). The baths, in other words, may have been a place of wonder, pleasure and beauty for the humble Pompeian bather. They might also have killed him.

Unsurprisingly, given the nakedness and the possible mingling of women and men (at least in Roman fantasy), baths were also associated with sex. Just like bars, some of them have been thought to be brothels masquerading under another name, with prostitutes lingering to pick up clients. The problem exercised Roman legal writers and jurists too. In trying to work out who exactly should suffer the legal penalty of being

infamis

for their involvement in prostitution, one writer cites a practice known ‘in certain provinces’ (not in Italy, in other words), where the bath manager has slaves to guard the bathers’ clothes, who offer a much wider range of services. Should he count as a pimp, Roman legal brains pondered – in theory.

In Pompeii we come face to face with this issue, in practice, in a set of baths situated just outside the city walls, next to the Marine Gate, and known now as the Suburban Baths. Excavated in the 1980s, these baths were a private commercial operation, located on the ground floor of a building which had domestic and other accommodation above. Much smaller than the public bathing complexes in the town centre, and with no sign of a women’s section, their attraction must have been the wonderful views they commanded over the sea, which bathers could enjoy from a spacious sun terrace (this was not the place to come to exercise). First built in the early first century CE, these too were undergoing repairs at the time of the eruption.

85. The men’s changing room from the Stabian Baths, before its restoration. Clearly visible are the stuccoed ceiling and, on the right, the ‘lockers’ for leaving clothes.

Their modern claim to fame is the changing room. High up on one wall you can still see eight scenes of athletic sexual intercourse, mostly couples (one of which

may

be two women), but also a trio and a foursome enjoying group sex (Ill. 86). These now survive on one wall only, but originally they would have appeared on two other walls, adding up to perhaps twenty-four different varieties of sexual position in all. Under the erotic scenes themselves, we find paintings of a series of wooden boxes or baskets, each one numbered (I–XVI still survive). Why the pictures of sex, and why combine them with pictures of numbered boxes?

The most likely answer lies in the simple fact that this was the changing room. Unlike the equivalent in the Stabian Baths, there were no built-in niches to leave your clothes, but still visible are the traces of a shelf running round the room under the paintings – on which individual boxes or baskets would have been placed. The paintings above serve to number the various baskets and to give the bather an amusing

aide mémoire

for remembering where he had left his kit: ‘number VI – that’s the threesome’. Others have wanted to push the interpretation further and suggest that these paintings acted as an advertisement for a brothel on the upper floor, or even as a menu of options for sale (‘Half an hour of number VII, please’). Perhaps this is also a case (as ‘in certain provinces’ ) where the slave girls in the changing room were doubling as prostitutes. Perhaps the graffito near one of the entrances to the upper floor, apparently advertising the services of Attice for the (high) price of 16

asses

, is to be connected to these paintings.