Pompeii (46 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

Figure 17

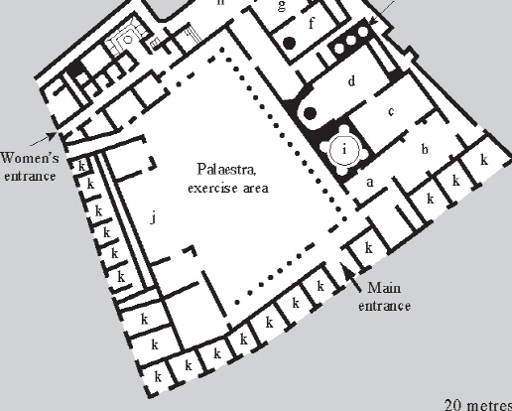

. The brothel. Nothing fancy here. The brothel was small and cramped. Apart from the lavatory, there was nothing but five tiny cubicles off a hallway. Where the money changed hands is far from clear – as is the use of the upper floor. Was it a separately rented apartment, or did it house the pimp and the girls?

The cubicles themselves are small, with short masonry beds, which would (one hopes) have been covered with cushions and covers, or at least something a bit softer than the hard stone. There is now no sign of any way of screening off the cubicles; but that may well be a consequence of the rough techniques of the 1860s excavators. If the view to the latrine was blocked by a substantial barrier, it is hard not to imagine at least a curtain which could be pulled across these doorways. Most, though not all, of the graffiti comes from inside the cubicles, and it is from these scraps of writing that we get some hints of who used the brothel and how.

The men who came here were not afraid to leave their names on the wall. So far as we can tell, these names include none of the well-known figures of the Pompeian elite. Prostitutes, as we already noted, were probably for those without ready access to the sexual services of their own slaves. The one man who clearly notes his job was an ‘ointment seller’. In fact, this collection of graffiti is one of the best indications we have that some command of reading and writing was found widely among the relatively humble people at Pompeii. Most of them sign up as individuals: ‘Florus’, ‘Felix went with Fortunata’, ‘Posphorus fucked here’. But occasionally, it seems, the customers came on a joint outing: ‘Hermeros with Phileteros and Caphisus fucked here’. This was possibly group sex, but more likely a boys’ night out.

The prostitutes themselves are harder to place. The names on the walls include a number of Greek or eastern women’s names (including, interestingly, a ‘Myrtale’ (p. 230), which can often indicate slave status. But these may be ‘professional’ names, assumed for the job, and so tell us nothing about the real background of the girls concerned. There is no clear evidence of any male prostitutes, though there are some references in the graffiti to sexual practices (such as buggery: in Latin

pedicare

, usually referring to men) which would not absolutely exclude the possibility that men as well as women worked here. Where there is a sign of prices, they are rather above the’2

asses

’ we often find on the walls of bars. One man, for example, claims that he ‘had a good fuck for a

denarius

[that is 16

asses

]’. This may mean that sex on the side with a serving girl came cheaper than in the brothel itself. It could be a further hint that the ‘2

asses

’ line was more of a conventional insult than a real price.

The layout of the graffiti within the building may tell us even more. One recent study has pointed out that the first two cubicles nearest the main entrance contain between them almost three quarters of the graffiti. Why? Possibly because they were used not just for sex itself, but as waiting rooms, so men had time here to scratch their thoughts and their boasts into the plaster. More likely, and more simply, these were the cubicles next to the street which were used more. You came in and took the first available ‘slot’.

How the brothel was organised, we can only guess. Were the girls who worked here slaves with a pimp owner who ran an organised business? Or was it all rather more casual? More freelance? One relevant factor is an upper floor, accessed by a separate entrance on the side street. This had five rooms, one considerably larger than the others, linked by a balcony serving as a corridor between them. There are no fixed beds here, nor erotic paintings nor surviving graffiti of any sort (though there is much less surviving decoration at all). There is nothing to prove what happened on this level. It could have been more prostitution. Or it could have been where the girls lived (and on this model the pimp perhaps occupied the larger room). Alternatively it was not directly linked to the brothel at all, but was a separate rented apartment (address: ‘above the brothel’). In which case, the working girls might simply have worked, lived and slept in those small cubicles.

It is, frankly, a rather grim place. And it is hardly improved by the stream of visitors who – since its restoration a few years ago – now make a bee-line for it. It usually proves to offer the tourist only a brief pleasure. It has been calculated that the average visit lasts roughly three minutes. The local guides meanwhile do their best to make it appealing, with not entirely accurate stories about the peculiar encounters that once took place in it. As some have been heard to explain: ‘The paintings have a practical purpose. The prostitutes couldn’t speak Latin, you see. So the clients had to point to a picture before they went in to let the girls know what they wanted.’

A good bath

A tombstone from Rome, put up some time in the first century CE to an ex-slave, Tiberius Claudius Secundus, by his partner Merope, includes the following piquant observation: ‘wine, sex and baths ruin our bodies, but they are the stuff of life –- wine, sex and baths’. Tiberius Claudius Secundus had not, in fact, done too badly, for he had lived to be fifty-two years old. But the wry sentiment blazoned here was almost certainly a popular Roman maxim. A version of it turns up, for example, as far away as Turkey: ‘Baths, wine and sex make fate come faster’.

So far in this chapter we have looked at the wine and the sex of ancient Pompeii. What about the baths: those three large sets of public bathing complexes in the town (now called, from their locations, the Stabian, Forum and Central Baths) and a number of smaller privately owned commercial establishments, catering to a public or semi-public trade?

Roman bathing was synonymous with Roman culture: wherever the Romans went, so too did Roman baths. Bathing in this sense was not simply a method of washing the body, though cleanliness was one part of its purpose. It was a mixture of a whole range of (for us) different activities: sweating, exercising, steaming, swimming, ball-gaming, sunbathing, being ‘scraped’ and rubbed down. It was Turkish bathing plus, with all kinds of further optional extras that might be added on, from barber’s services to – in the very grandest metropolitan versions – libraries. The bathing complexes that were designed to house all these activities were some of the largest and most elaborate and sophisticated pieces of architecture in the Roman world. In Pompeii, the three main public baths together occupy a space larger than the Forum itself, even though they are tiny by comparison with the vast schemes of the capital. The whole of the Forum Baths at Pompeii would fit easily into the swimming pool of the third-century CE Baths of Cara-calla at Rome.

The baths were both a social leveller and one of those places where the inequalities of Roman society were most glaringly on display. Everybody except the very poorest went to the baths, including some slaves – even if they were only acting as retinue for their master. The very richest did have their own private baths at their home, as in the grand House of the Menander at Pompeii. But, as a general rule, the well-off would have shared their bathing with those less fortunate than themselves. In other words, unlike for dining, they went

out

to bathe.

On the one hand, the conventions of bathing brought everyone down to size. Bathing naked, or nearly naked (there is evidence for both practices), the poor were in principle no different from the wealthy – possibly healthier and of finer physique. This was Roman society on display to itself, without all those usual markers of social, political or economic rank: striped togas, special ‘senatorial’ sandals or whatever. It was, as one modern historian has put it, ‘a hole in the ozone layer of the social hierarchy’.

On the other hand, the stories which Roman writers tell about baths and bathers return time and again to competition, jealousy, anxiety, social differentials and ostentation. This was partly a question of the body beautiful, for both men and women. According to one ancient biographer, the emperor Augustus’ mother could not bear to go to the baths ever again, after an unsightly mark appeared on her body when she was pregnant (it was in fact a sign of the divine descent of her son). And the poet Martial wrote a pointed epigram about a man who laughed at those with hernias, presumably in the baths, until he was bathing one day and noticed he had one himself.

But it was also a question again of displaying (and pulling) rank. A notorious incident in the second century BCE involved a consul’s wife, who was travelling in Italy and decided that she wanted to use the men’s baths in a town not far from Pompeii (the men’s suite must have been better appointed than the women’s). So not only did she have the men thrown out, but her husband had the local elected

quaestor

flogged for not clearing them out quickly enough, and not keeping the baths themselves clean.

One nice variant on this theme, with a happier ending, concerns the emperor Hadrian. The story is told that when he was visiting the baths one day (for even emperors might bathe in public – or make a point of so doing once in a while) he noticed a retired soldier rubbing his back against the wall. When questioned, the man explained that he could not afford a slave to rub him down. So Hadrian gave him some slaves and the cost of their maintenance. Returning on a later occasion, he found a whole group of men rubbing their backs on the wall. The cue for another act of imperial generosity? No. He suggested that they should rub each other.

There was also some edgy ambivalence about the moral character of the baths. True, many Romans assumed that bathing was good for you, and indeed it might be recommended by doctors. But there was at the same time a strong suspicion that it was a morally corrupting habit. Nakedness, luxury and the pleasures of hot, steamy recreation were in the eyes of many a dangerous combination. It was not only the noise that worried the philosopher Seneca, when he complained about living above a set of baths.

Archaeologists have tended to stereotype and normalise Roman baths much as they have Roman houses. An array of Latin names are applied to the various parts of the cycle of cold and hot rooms:

frigidarium

(cold room),

tepidarium

(warm room),

caldarium

(hot room),

laconicum

(hot sweat room),

apodyterium

(changing room) and so on. These terms were sometimes used by Romans themselves. In fact, an inscription in the Stabian Baths at Pompeii records the installation of a

laconicum

and a

destrictorium

(a scraping room). But they were not the standard everyday words that modern plans and guidebooks suggest. I very much doubt that many Romans would, in practice, have said, ‘Meet you in the

tepidarium

.’

Nor was there the kind of fixed procedure in the baths that these impressive Latin terms encourage us to think. Archaeologists are almost always too keen to systematise Roman customs. Although we are often told by experts on the baths that the principle of Roman bathing was to move through progressively hotter rooms, before going back to the beginning and finishing with a cold plunge, there is no firm evidence for that. All kinds of different pathways would have been possible (and, in fact, some experts hold the opposite view that they worked through from hot to cold). Nor is there any reason to suppose that a visit would always have required a couple of hours, minimum, or that visits for men were always in the afternoon. Practice was almost certainly much more varied, procedures much more ‘pick and mix’, than the modern desire to impose rules and norms would have us believe.

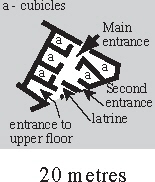

The variety of opportunities and entertainments offered by a relatively large bath complex will become clearer if we take a look at the Stabian Baths at Pompeii (Fig. 18). One of the three main sets of public baths in the centre of the town, these were – like so much else – under repair at the time of the eruption, with only the women’s area in full working order. In fact there must have been a certain pressure on bathing space in Pompeii in 79. Of the public baths, only the Forum Baths were operating to capacity. A brand-new set (the Central Baths) were being built to the most up-to-the-minute designs but had not yet been completed. Even the private commercial establishments, which tended to be smaller than those operated by the city, and which might have been more picky about their clientele, were not all up and running. One, for example, had been in ruins for many years (perhaps a commercial failure), and the so-called Sarno Baths on the lower floors of an apartment block were being restored. Those on the Estate of Julia Felix, ‘an elegant bath suite for prestige clients’ as the rental notice puts it, were one of the few in operation – and were presumably, given the likely demand, a nice money spinner.