Pompeii (58 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

110. The little Temple of Isis still captures the modern imagination much as it did that of eighteenth-century visitors. Because it was in full working order at the time of the eruption, and not looted in the years that followed, it offers the most vivid picture of a religious centre in the town.

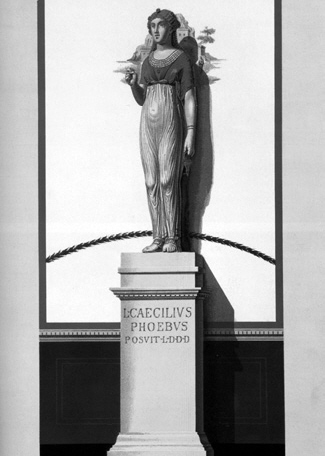

The overall impression is one of cultural mix. Here, for example, standard classical portraits (such as the bronze of mime actor Norbanus Sorex) and sculptures of traditional deities such as Venus rub shoulders with ‘real’ Egyptian bric-a-brac, such as a fourth-century BCE tablet from Egypt inscribed in hieroglyphs – presumably intended to evoke ‘authentic’ Egypt. We see this mixture too in the best-preserved image of Isis from the complex (Ill. 111). This statue was made in the first century CE, adopting a Greek style of sculpture of several hundred years earlier. She is hardly Egyptian at all, but for the characteristic rattle or

sistrum

she carries in one hand, and the ankh, or Egyptian cross, she once carried in the other. It is hard to resist the feeling that this cult is treading a fairly safe line between its traditional civic Italian links and its mystical Egyptian ‘otherness’. That is the message too from all those Egyptian deities who shared space on the household

lararium

with little models of Lares, or Hercules, or Mercury.

The traditional aspects of the Isiac cult are well illustrated by the inscription above the main entranceway, recording the restoration. It reads: ‘Numerius Popidius Celsinus, the son of Popidius, restored with his own money the Temple of Isis, from its foundations, after it had collapsed in the earthquake. On account of his generosity, the decurions co-opted him onto the town council, without fee, although he was only six years old.’ There are other signs of this family’s benefactions in the temple. Celsinus’ father, ‘Numerius Popidius Ampliatus, senior’ donated a statue of Bacchus. Their names also used to appear in black and white mosaic, along with that of Corelia Celsa (presumably wife and mother) on the floor of the

ekklesiasterion

.

As we have already seen, it looks as if the elder Popidius was using the restoration of this temple to launch his young son into the Pompeian political elite. We do not know for sure that Popidius Ampliatus was an ex-slave and so precluded himself from political advancement in the town, but a man of that name does appear among the ‘attendants of Augustus’, who were predominantly slaves or ex-slaves. So that seems very likely. What is more interesting though is that restoration of the Temple of Isis so easily counts in the game of benefaction and generosity that characterised civic advancement in Pompeii. Initiatory, foreign and strange, the Isiac cult may have in some respects been. But the bottom line was that it was a public cult, on public land, as plausible a vehicle for social advancement as that of Fortuna Augusta. Isis was one religious option among several for the inhabitants of Pompeii.

In the 1760s, the Temple of Isis was among the first buildings fully excavated on the site. It was a lucky find and it instantly captured the imagination of European travellers. True, a few killjoys found it disappointingly small. But for most it offered double excitement: simultaneously a glimpse of ancient Egypt and of ancient Rome. Exotic and a little bit sinister, it gave Mozart, who visited Pompeii in 1769, ideas for the

Magic Flute

. Fifty years later, it gave Bulwer-Lytton the idea for the nasty conniving villain of his

Last Days

, the Egyptian Arbaces – who was written up with all the predictable racial stereotypes. But it was responsible for even more powerful myths too. For it was the pristine state of the temple, almost undisturbed, that helped to create ‘our’ myth of Pompeii, a city interrupted in mid-flow.

111. A nice illustration of the cultural mix represented by the cult of Isis at Pompeii, straddling the traditions of Egypt, Greece and Rome. This nineteenth-century painting shows a statue of the goddess herself, holding Egyptian symbols. But the figure itself looks back to a recognisably Greek style of sculpture.

In fact, the last sacrifice was still burning on the altar here when the pumice started to fall. Or so they said.

Ashes to ashes

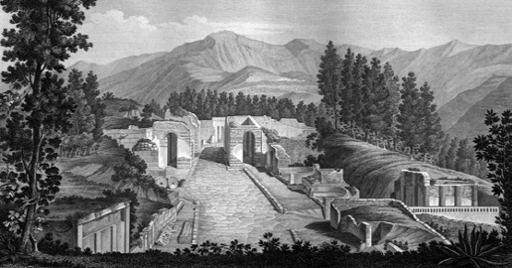

Early visitors to the remains of Pompeii entered the city through its cemeteries. We now buy our tickets, maps, guidebooks and bottles of water in a modern ‘visitor centre’, which could just as well be the entrance to a busy train station as to a buried city. Our eighteenth-century predecessors usually followed one of the ancient roads into the town, lined as they were with imposing and affecting monuments to the dead.

Romans kept the dead out of their towns. There were no city-centre cemeteries or village graveyards, putting the dead in the middle of things. Instead, here at Pompeii just like in Rome itself, the memorials to earlier generations hugged the routes in and out of the town outside the walls. Ancient travellers entered Pompeii past the often imposing residences of those who had lived decades, maybe centuries before. For although cremation was the normal funerary practice during the heyday of Pompeii (at least since the arrival of the Roman colonists in the early first century BCE), this did not discourage extravagant memorials. Tiny urns holding the ashes of the dead were lodged in a whole range of grand designs – in the shape of altars, elegant semi-circular seats or benches, (convenient resting places for the living too), multi-storey constructions with columns and statues of the departed.

For the early tourists this set the tone for their visit. Pompeii was a site of human tragedy, a city of the dead. The tombs they first saw as they started their visit (albeit the memorials of those who, likely as not, had died safely in their beds) offered the prompt to a good deal of reverie on the transience of human existence, and on the inevitabity of death for all of us, high or low. Dust to dust, and – appropriately for Pompeii – ashes to ashes.

But, of course, death and commemoration was anything but equal in ancient Pompeii. The memorials reflected exactly those hierarchies and inequalities that we have seen repeatedly in the life of the town. We already spotted (pp. 2–4) the irony of that little party of unsuccessful fugitives, with some 500

sesterces

between them, being finally overwhelmed next to the tomb of Marcus Obellius Firmus, aedile and

duumvir

, whose funeral alone had cost ten times that amount. His tomb was typical of the grander designs, though by no means the most splendid: a simple walled enclosure, within which the single urn was buried, with a terracotta pipe installed next to it, to channel offerings made to the dead man by his descendants. Unless they had been convinced by the more optimistic claims of some of the newer religions, most Romans had, it seems, a rather hazy and grey picture of what happened after death. Nonetheless, as here, they might take the trouble to provide some kind of sustenance for their ancestor – though how often the tube was used we do not know.

Other members of the Pompeian elite, both male and female, were commemorated with more flashy monuments than Obellius Firmus. In fact, the tomb of the priestess Eumachia is the biggest so far uncovered, standing high above the road on its own terrace and including – a wry reflection on her gender, as it must now seem – a marble sculpture of Amazons (mythical female warriors), a large seating area and the burial plots of Eumachia herself and some of her relations and dependants. On some, the honours or benefactions of the deceased were displayed in images as well as words. We have already seen (Ill. 72) the

bisellium

or seat of honour carefully carved onto the tomb of the

Augustalis

Caius Calventius Quietus, as proud an assertion of status as any made by the richest aristocratic landowners. Others carry sculptures or paintings of gladiatorial contests – presumably intended to represent those financed by the dead man during his lifetime.

Many of these monuments ended up marked with graffiti of the usual demotic type, or covered with publicity notices for games and shows. Their plain walls must have provided a convenient space for messages and adverts in a prominent roadside location. But it is hard not to suspect that there was also an element of ‘getting your own back’ at work here. How satisfying it must have been to deface these aggressive memorials to wealth, power and privilege.

Needless to say, the poorer sections of Pompeian society did not enjoy such luxurious final resting places – unless they were among those slaves and ex-slaves lucky enough to be granted space in their masters’ monument. For the rest, some would have been able to afford a small part of a large communal tomb. The ashes of others ended up in cheap containers inserted directly into the earth, marked with just a simple stone. Even that would have been too good for those at the very bottom of the social pile. At Pompeii, as elsewhere in the Roman world, their bodies were probably unceremoniously dumped or burnt, with not a funeral celebration or permanent marker at all.

112. Street of tombs. This engraving captures the approach to the city for the early visitors. Entering the city by the Herculaneum Gate, they came face to face with the monuments of death. On the right, just visible is the semi-circular seat which formed the memorial to the priestess Mamia – celebrated by Goethe in his account of a visit to Pompeii.

Quarrels beyond the grave

It was not only the inequalities of Pompeian life that left their permanent mark in the cemeteries outside the town. Occasionally the quarrels and disputes of the living city extended beyond the grave. In fact, one of the most vivid glimpses of the rough realities of ancient society, a sad story of friendship made and lost, comes from a large tomb outside the Nuceria Gate, located near the monument of Eumachia. It is the memorial of an ex-slave, Publius Vesonius Phileros, who built it well in advance, during his own lifetime, for himself and for two others to share. It is a nice indication of the fluidity of relationships and affections, cutting across the formal hierarchies of Pompeian society. For Phileros built a tomb to include also the remains of his one time owner, a woman named Vesonia, and his ‘friend’, a free-born man by the name of Marcus Orfellius Faustus. Full-length statues of all three of them – sadly missing their heads – still look down at the passers-by from a niche on the upper storey of the façade.