Pompeii (54 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

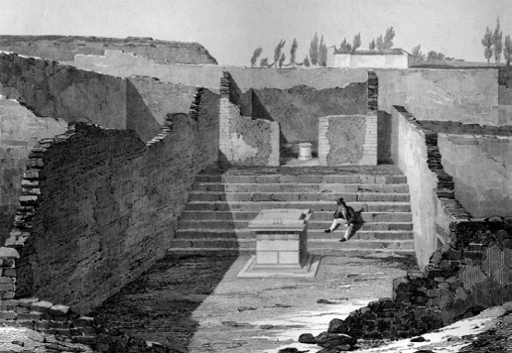

102. An early traveller takes a rest – or seizes the chance for some romantic reflection on the passing of time – in the ruins of the tiny Temple of Jupiter Meilichios (or Aesculapius). Even this very small building shows the standard structure of a Roman temple: a room (or

cella

) to house the statue or statues of gods, and an altar outside.

Sometimes the gods associated with the temple are easy to identify. The temple in the commanding position at one end of the Forum, for example, can only be that of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva – located in this prime site as in many, if not most, Roman towns (Ill. 100). The goddess Fortuna Augusta is clearly named in the inscription. For several others we are reduced, for better or worse, to conjecture. The vast temple overlooking the sea, next to the Marine Gate, was very likely the Temple of Venus – but there is no firm evidence for this beyond a battered statue and our conviction that there must have been a substantial temple to the colony’s patron somewhere in the town. The tiny temple tucked almost out of sight, behind high precinct walls near the theatres, has proved a real puzzle (Ill. 102). Archaeologists have recently returned to the theory of J. J. Winckelmann, the ‘Father of Art History’, who visited Pompeii in the mid eighteenth century and called this a temple of Aesculapius, the god of healing – again on no firmer evidence than a statue found there which may have depicted the god. Others have called it the Temple of Jupiter Meilichios (‘honey sweet’ – a title connected with the gods of the underworld). This is on the basis of an inscription which refers to a temple of that name. If it is not the Temple of Meilichios, then that must still be waiting to be found somewhere else in the city (or, as some now think, outside – matching it up with a shrine beyond the city walls). There is, as we shall see again, a domino effect in many of these conjectures – one identification can easily topple another.

The overall design of these temples may be familiar. What went on inside them is much less so and much more surprising. Temples were not places where a congregation of worshippers gathered or where religious rituals were carried out. The essential function of any Greek or Roman temple was to house a statue of a god or goddess. We should not imagine bloody sacrifices carried out in the dark inner room of any of these buildings. These always took place outside in the open air. The temple was the home of a divine image, or ‘cult-statue’. The most common Latin word for it,

aedes

rather than

templum

, means simply ‘house’.

Yet only rarely would the statue have stood entirely on its own. Many temples acquired a lot of clutter, sometimes very precious clutter. Dedications and offerings to the god or goddess in fulfilment of a vow often ended up here. Someone might, for example, promise a gift to Aesculapius if he got better from his illness – and, on recovery, deposit what he had promised in his temple. Statues and other works of art were often displayed here too. In Rome itself, temples were a favourite place to house rich pieces of booty captured in war, or the authoritative texts of laws inscribed on bronze tablets. And all kinds of other activities might also have gone on around the statue of the god. The Roman senate used the space inside several temples for its own meetings, some of the wealthiest citizens deposited their wills in the Temple of the goddess Vesta, and the basement of the Temple of Saturn served as the Roman state treasury. All these valuables mean that they must have been well-policed by their caretakers (security guards, cleaners and maintenance men rolled into one), firmly locked at night and open to the public only under supervision.

This was the pattern at Pompeii too. The traces are, at first sight, more fleeting than we might hope – whether because, like the Temple of Venus, these temples were in the middle of building works when the eruption came, or because their precious fixtures and fittings made them an obvious target for looters after the eruption (the archaeological remains, after all, being much the same in each case). Alternatively, of course, their loyal caretakers may have removed some of the more precious objects as they fled the eruption.

But all kinds of telling pieces of evidence do survive. We have already seen the piece of booty from the capture of Corinth in 146 BCE that was put on show in or near the Temple of Apollo. This same temple also displayed a magnificent pair of bronze statues, of Apollo and Diana (only her head now survives) in its piazza, as well as a replica of the strange

omphalos

(that is the ‘navel of the earth’) which was one of the sacred symbols of Apollo’s famous shrine at Delphi – and another example here of Pompeii’s wide cultural reach. We even get a hint of the security systems that these temples might use. Still visible along the front façade of the Temple of Fortuna Augusta are the remains of metal railings, which could close the building off (Ill. 103). One leading expert on Pompeii once assured me that these had been a nineteenth-century addition, designed to stop tourists climbing on the monument. That is just what they look like. But they were actually intended to keep ancient Pompeians out.

Even some of the town’s most ruined monuments can give us more information on temple life and organisation than we would suspect at first sight, tantalising glimpses of their cult statues and the other riches which once were there, and sometimes unexpected stories of what was going on in Pompeii in 79. A good case in point is the Temple of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, which at least from the arrival of the Roman colonists housed the trio of deities which defined Pompeii as a Roman town. It is frankly not much to look at now (Ill. 104). Its steps and some sadly truncated columns remain at the front. On top of the podium, the inner room of the temple is still clearly visible, and within it the scant remains of what was once a two-storey internal colonnade. At the far end are the niches which would have displayed the statues of the three gods. In its present state, it is grim and functional. But we get a vivid ancient view of it in one of the small friezes in the House of Caecilius Jucundus (Ill. 5). Although the intention of this sculpture was to demonstrate the damage done by the earthquake (damage from which this temple perhaps never recovered), it also offers us a nice – maybe slightly imaginative – snapshot of the building in its original setting, complete with some of its decoration. The altar stands outside on a platform set into the steps of the temple. On either side of the steps we find an equestrian statue, while behind the altar, by leaving out two of the six columns, the sculptor has been able to show us the doors leading into the inner room and, above, a garland or wreath decorating the pediment.

We have other clues about the building’s original appearance and its use. First, the podium on which the temple stands is not solid. It is hollow, and contains a basement room, which you could reach either via some stairs from inside the temple, or through a door at pavement level on the east side. Light was brought into this basement by shafts set into the floor above. This fact alone suggests that the room had a practical use. For why provide lighting if no one was likely ever to go into it? One idea is that it was intended as a store for the surplus dedications from upstairs: whenever the temple caretaker felt that a clearout was needed, he would not throw the pious offerings out, but carefully stash them away in the basement. Another is that it was the city council’s treasury or bank vault, just as the treasury at Rome itself was in a temple cellar. Either is possible. But sadly there is no indication that anything was in there at the time of the eruption apart from some assorted pieces of sculpted marble.

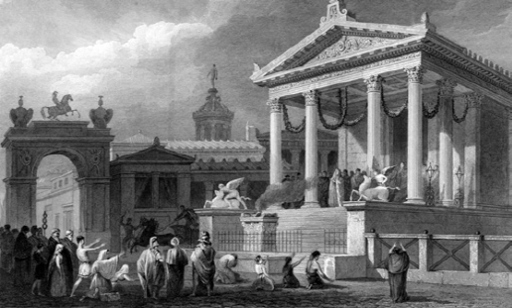

103. This nineteenth century reconstruction of the Temple of Fortuna Augusta rightly imagines the religious rituals taking place outside the temple and in its portico. The artist has included the metal railings (though not at a height to keep a vandal out) and has brightened up the exterior with festoons. But the crowd of worshippers in front seem implausibly flamboyant.

104. The now rather desolate ruins of the Temple of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva. How dilapidated this end of the Forum was at the time of the eruption is still disputed.

There are also clear signs that it was once much more richly decorated than it appears today. The floor was inlaid with geometric patterns of marble (so-called

opus sectile

) and the walls of the inner room were brightly painted. These paintings are now faded almost beyond recognition, but they were clearly visible when the building was first excavated in the early nineteenth century and when this temple was one of the star attractions of the site. In fact it was this spot that the poet Shelley chose for his picnic when he visited Pompeii in December 1818. Even if it was originally rather dark – for there is no obvious source of light except the main doorway – the inner room, with colonnade, statues, rich fittings and offerings, must have been an impressive sight. At more than 10 by 15 metres, and with the doors left open so you could see what you were doing, it would have been a place for the local council to meet.

That is, if there was not too much clutter and bric-a-brac getting in the way. The nineteenth-century excavators found a few inscriptions recording dedications for vows fulfilled (including one for the ‘well-being’ of the emperor Caligula), and the base of a statue put up in honour of a man, Spurius Turranius Proculus Gellianus, who had held various posts in Rome and the town of Lavinium. What his connection with Pompeii was, and quite why he was given a statue in this particular place of honour (if this was its original location), we have no idea. The excavators also turned up, in and around the temple, a good haul of bits and pieces of sculpture. As William Gell describes it in the 1830s, giving a nice flavour of the curious assemblage: ‘Many fingers of bronze were discovered ... a group representing an old man in a Phrygian cap taking a child by the hand, half a foot high; a woman carrying her infant ... a hand, a finger, and part of a foot, in marble; two feet with sandals; an arm, and many other colossal fragments.’

Standing out amongst all this was a colossal marble torso, which could only have come from the statue of a god, and two striking heads: that colossal bearded marble head of Jupiter himself (Ill. 99), and a smaller female head (Juno or Minerva). These heads have often been thought to be all that is left of the cult statues of the three deities. If so they must have been what we now call ‘acrolithic’ sculptures (literally ‘stone extremities’). This was a favourite ancient method of making huge images that would have been too big, heavy and costly to make out of solid marble, and much, much too costly to make entirely out of bronze. It involved constructing a frame out of wood or metal, covering most of the frame with rich clothing, and using marble just to stand in for the skin of hands, feet and faces. This partly explains why museums of ancient sculpture are now rather over-provided with large marble extremities. It is not only because they break off easily (which they do). It is because hands, feet and heads were often all that was made in marble in the first place.

But a more careful look at these remains produces a strange picture of the Temple of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva at the time of the eruption. For a start the male head and colossal torso cannot possibly belong together. Then there is the puzzle of why these parts of the precious cult images were found just lying around. Perhaps it was the result of an inefficient rescue job as the volcano exploded, or of hurried looting later. But if, as seems more likely in this case, the general disarray in the temple was caused by restoration works in progress (after one or more earthquakes) why was such little care taken with the old statues? Were the authorities really happy that parts of their venerable old images were just scattered on the temple floor? Most curious of all, on the back of the marble torso there is another sculpture in relief, showing three small figures. The marble has obviously been reused. This heroic male chest has, recently we would guess, been carved out of an earlier relief sculpture. All these factors, combined with the haul of other very fragmentary pieces, have made some archaeologists think that in 79 the building was not merely being restored, but it was actually temporarily decommissioned as a temple and was being used as a sculpture depository, workshop and site office. No need to worry about the careless treatment of the old cult statues. What was found here, impressive as some pieces are, were just the spare fragments in the depository.