Pompeii (52 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

95. One of the bronze helmets found in the gladiators’ accommodation. Like the others, it is so richly decorated (here with an image of the goddess ‘Rome’) and in such good condition, that it is hard to imagine that it has seen active combat. Much more likely it is part of the gladiators’ ceremonial or parade dress.

How are we so certain that these were gladiatorial quarters? The simple answer lies in the extraordinary finds of bronze gladiatorial armour and weapons in ten of the rooms around the peristyle. These added up to fifteen richly decorated bronze helmets, fourteen shinguards, six shoulder-guards, as well as a small assortment of daggers and other weapons. Most of these are richly decorated, with scenes from classical myth or emblems of Roman power. One helmet, for example (Ill. 95), displays a personification of Rome itself, surrounded by defeated barbarians, prisoners and trophies of victory. Strikingly they are all in a perfect state. Not one shows any sign of ever having been used in fighting. These may well have been the parade collection, such as we saw carried along in the representation of the opening procession at the games. If so, nothing survives of their day-to-day fighting equipment.

The prospects for these gladiators were grim, but not quite as bad as we might fear. The good news for them was that they were an expensive commodity. Many of them would have been bought at a price; and all of them would have used up many of the

lanista

’s resources in their training and keep. He would not want to waste them. Even if gladiatorial shows in which no one was ever killed would hardly be crowd-pullers, and even if the sponsor wanted his money’s worth, it would be in the troupe manager’s interests to keep the deaths to a minimum. It would surely have been part of the deal between

lanista

and sponsor that when a fighter lost, more often than not the sponsor should give a lead to the crowd in allowing him to be reprieved, not to put him to death there and then. Needless to say, that must have been the instinct of the gladiators too. Training and living together, and no doubt becoming friends, they would hardly have been going all out for the kill.

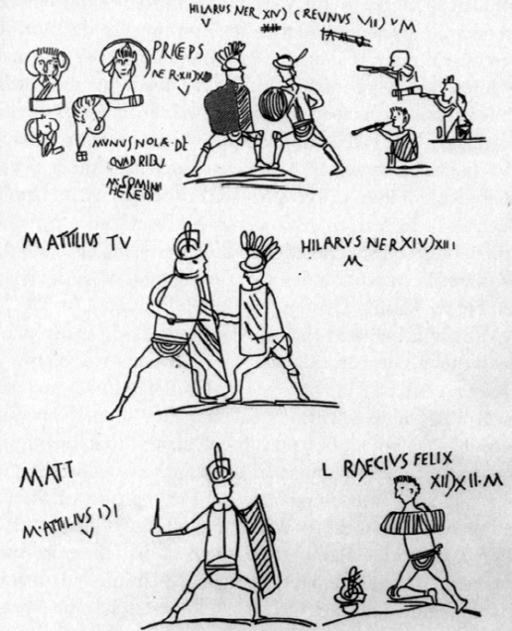

96. This vivid record of three gladiatorial bouts at Nola (the place is mentioned next to the topmost pair of fighters) was found scrawled on the outside of a tomb. One of the fighters is a first-timer. The middle register features M(arcus) Attilius who is marked down as a ‘novice’ (‘T’ for

tiro

). After his first victory (‘V’ stands for

vicit

), he goes on to win his second fight against the more experienced L(ucius) Raecius Felix. The musicians shown at the top remind us of what a noisy occasion these games must have been.

That is certainly the picture we get from the Pompeian graffiti which record the results of particular bouts of fighting. One of the most evocative examples is a set of drawings with accompanying captions found on a tomb, depicting a four-day series of games at nearby Nola (Ill. 96). The gladiators are a mixture of old hands, with thirteen or fourteen fights to their name, and a novice undertaking his first two fights. None of the losers are killed, for next to each of their pictures there appears the letter ‘M’ for

missus

, or ‘reprieved’. From the record of the gladiators’ ‘form’ that is also recorded (‘fought 14, victories 12’) we can tell that two of the losers had been spared at least twice before. In the show presented by Mesonius, on one day nine pairs of gladiators fought. Out of these eighteen, we can still identify eight outright victors, five men reprieved and three men killed. Occasionally a Pompeian gladiator is recorded as fighting more than fifty fights.

Nonetheless, even if defeat often did not mean death, the loss of life must have been by our standards considerable. To put exactly the same figures in a less upbeat way, three dead out of a total of eighteen gladiators, suggests a death rate of about 1 in 6 in each show. Small as the sample is, it fits with the overall record of numbers of fights fought by each gladiator for whom that total is recorded. True, there are a few old-stagers, but only a quarter of those we know have more than ten fights to their name. If we reckon, the other way round, that three quarters would have died before their tenth fight, that means a loss rate of some 13 per cent per fight. Even assuming that they did not fight very often (two or three shows a year is one estimate), if they entered the arena at the age of seventeen they could expect to be dead by the time they were twenty-five.

But if longevity did not come with a gladiatorial career, celebrity perhaps did. There were clearly some star gladiators whose names were paraded on the advertisements for shows, including one beast-fighter too, called Felix, whose match against some bears was specially highlighted in one notice. The figures of gladiators, in their distinctive armour, are also found throughout the town, and in every medium you can think of. They turn up as little figurines, as images on pottery lamps, and forming the handles of bronze bowls. One statue of a gladiator, more than a metre high, seems to have done duty as a kind of trade mark, or inn sign, at one tavern near the Amphitheatre. Gladiators would have seen their own images all over the place.

It is also commonly said that they had enormous sex appeal for the women of Pompeii and elsewhere in the Roman world. The satirist Juvenal writes of some imaginary upper-class Roman lady who runs off with the great brutish figure of a gladiator, obviously attracted by the ancient equivalent of ‘rough trade’, and by the glamour that his dangerous life brought. The Roman imagination certainly saw the gladiator in these terms. But we find a cautionary tale when we try to follow this fantasy through to the real life of Pompeii. We have already seen (p. 5) that the myth of the upmarket Pompeian lady being caught red-handed in the gladiatorial barracks, with her gladiator lover, is just that: a myth. But some of the other evidence for the sex appeal of the gladiators requires a second look too.

Some of the most famous graffiti from Pompeii are about two particular gladiators and their female fan club. ‘Celadus, heartthrob of the girls’, ‘Celadus, the girls’ idol’, ‘Cresces, the net-man, puts right the night-time girls, the morning girls and all the others’. It would be nice to think of some love-struck Pompeian women wandering around the town and immortalising their passion for Celadus and Cresces on the walls they passed. And that indeed is how they are often treated by modern scholars. But it is not so simple. These graffiti were found inside the old gladiatorial barracks. They are not the fantasy of the girls. They are written by the gladiators themselves – simultaneously bloke-ish boasting and the poignant fantasies of a couple of young fighters, who faced a short life and may never have got their girl, or at least not for long.

When it comes to reconstructing the everyday life of an ancient, it matters a very great deal where exactly your evidence is found.

Those other inhabitants

Pompeii teemed with gods and goddesses. Whatever they would have made of the rest of my account, it would certainly have surprised the inhabitants of the ancient city that, so far, I have tended to leave in the background the various deities who bulked large in their lives. The city contained literally thousands of images of these gods and goddesses. If you count them all, big and small and in every medium, they were probably more in number than the living human population.

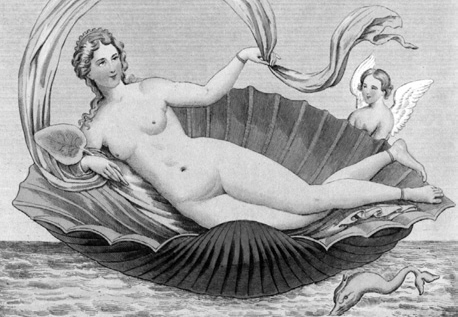

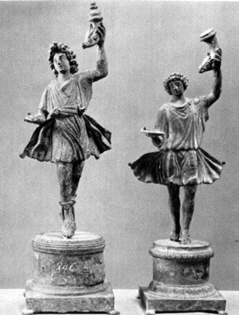

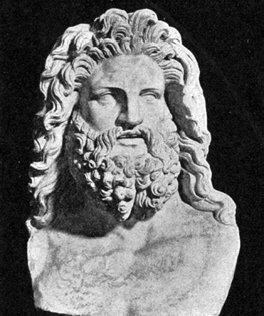

They certainly came in all sorts, shapes, sizes and materials – ranging from the large painted pin-up Venus (Ill. 97), sprawling awkwardly across a massive seashell which pointed to her mythical birth from the waves, to miniature dancing bronze figures of the Lares or ‘household gods’ (Ill. 98) or a little bronze bust of Mercury used to balance a set of weighing-scales. Some were presumably intended to prompt feelings of reverence and awe: the large marble head of Jupiter, for example, found in his temple in the Forum (Ill. 99). Others, such as the boisterous caricatures in the private baths in the House of the Menander (Ill. 51) or some of the more overblown phallic versions of the divine Priapus (Ill. 36), must have been joking parodies. Others again, such as a self-consciously old-fashioned bronze Apollo from the House of Julius Polybius, were no doubt valued as precious

objets d’art

, as much as they were revered as sacred images. Many of the standardised images of Minerva in her long robes and helmet, or Diana in hunting gear, would have seemed safely traditional. Not so the ivory figure of Indian Lakshmi (Ill. 11) or the miniature images of the dog-headed Egyptian god Anubis. To some Pompeians these would have seemed at best troublingly exotic, at worst weird and dangerous.

97. Roman gods were imagined in variety of guises. This Venus, with little Cupid in attendance, seems disconcertingly like a modern pin-up.

98. Bronze figurines of the ‘household gods’ or Lares, dressed in their characteristic tunics (said to be made of dog-skin) and carrying an offering bowl and brimming cornucopia (horn of plenty).

99. The majestic face of Jupiter. This colossal head was found in the remains of the Temple of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva in the Forum.