Practical Genius (2 page)

Authors: Gina Amaro Rudan,Kevin Carroll

Gina’s book,

Practical Genius,

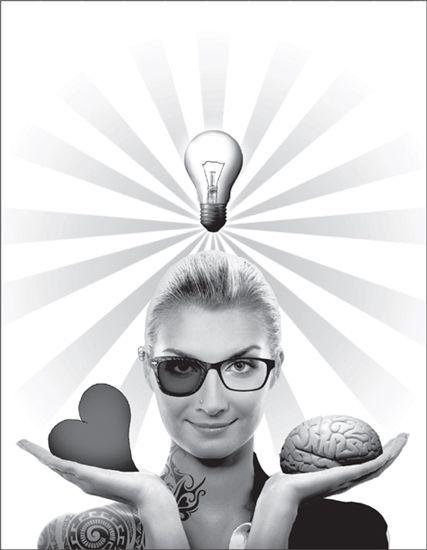

brought back powerful memories of this lesson, how it took root in me and shaped the way I live and work and play in the world. “We all have our very own innate genius, an intellectual sweet spot located somewhere between our heart and mind,” Gina writes.

I live at that sweet spot, thanks in part to Nana Carroll sharing her genius with me. Be still now, and begin the journey of

Practical Genius

that will show you how to live in yours, too.

Kevin Carroll

www.kevincarrollkatalyst.com

GENIUS

GENIUS

RANCESCA PRADO

Where the Journey Begins

Do you ever feel as though you are two separate people—the face you present at the office and the authentic self you are in the rest of your life?

Do you feel as though there’s a whole set of your skills, talents, and assets that you’re not using every day because you’ve allowed what you do for a living to become what you are?

So many of us wake up every day to a dreaded alarm clock that drags us from the comfort of our cozy beds to pitch us into daily routines—routines that we have willingly chosen but often can’t quite remember why. Many of us go to jobs, earn a living, maybe we’re even doing what we are good at for eight hours a day (or more).

But most likely we’re not doing what we love. We march through the stages of life—college, career, marriage, kids, more career—and we wake up one day and twenty or thirty years have passed, and we wonder, “Hey, what was that? What do I have to show for it? Who

am

I?”

How do smart, motivated, accomplished people like us, who are walking around with all the human assets one could ever hope for, end up in this no-man’s-land? How did we fool ourselves into believing that this was the best we could do?

The great American engineer and futurist Buckminster Fuller once said, “Everyone is born a genius, but the process of living degeniuses you.” That’s a fact, Jack, and it’s why we have two types of problems:

You’re going through the motions, armed with the latest technology and a closet full of career wear, and you’re thinking “This is okay, I’ve got a good life” while ignoring the fact that there is a whole other side of you that lies dormant, eager to be released from the tidy cage of your conformity. You are one of the millions battling with the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde syndrome, checking half of yourself at the revolving doors of your office building, walking through your workday with an unconvincing smile, sitting silently in one too many meetings doodling a masterpiece in your Moleskine notebook.

If this sounds like you, you have allowed yourself to be degeniused.

You’re a die-hard creative person working from a home studio, swimming though life with the imaginative right side of your brain leading the way while the practical left side is unactivated. You pass your days, months, and years waiting patiently for a “lucky break.” You bounce from inspiration to inspiration, passionately invested in the creative process but not in the

business

of being creative.

If this is who you see in the mirror every day, you, too, have allowed yourself to be degeniused.

So many of us are unconsciously compromising some of our greatest natural assets because of external factors, past hurts, or current fears. Or, even worse, we have sacrificed our skills, strengths, and passion to the expectations and influence of others. Or we’re consciously hitting the snooze button, rolling over and going back to sleep every time we’re reminded how far from feeling happy and fulfilled we are in our work and personal lives.

I call this the “degeniused self,” and he has been allowed to sit in the driver’s seat of our lives for far too long. The degeniused self sabotages your potential, holds you back, and accepts mediocrity. This is the side of you that operates from fear and shines dimly, if at all. This is the person who has allowed people, organizations, environments, and circumstances to beat the genius out of you. Enough already!

“Will all the geniuses in the room please raise their hands?” I ask this question at every corporate training session I facilitate, and it astonishes me how few hands go up. Regardless of the industry—whether I am speaking to an auditorium full of bankers, marketers, or scientists—most people hesitate, look around to see who else has raised their hands... and shyly choose

not

to outwardly demonstrate their belief in their own genius.

If I asked you the question right now, how would you respond? Would you confidently say, “Here I am!” and acknowledge the spark of genius within you? Or would you hesitate and stammer that you’re “not so smart, not so special, not really.”

The second response was the one I most often received when I first started my Genuine Insights practice, and I must admit it drove the marketer in me crazy. When I discovered how many of my clients had no idea if they even had a drop of genius inside them, I realized I was looking at both a crisis and an opportunity—an opportunity

I seized. So many professionals know exactly what their career strengths and skills are, but the recognition of their most potent ingredients obviously stopped short. Some folks would stare back at me puzzled, not sure how to answer the simple question “What contributes to your genius?” Or they would dismiss the question entirely, not believing it had any relevance to them at all.

I’ve been studying this concept of “genius” for years now. In that time, I’ve interviewed hundreds of professionals and asked them for their definition of genius. I’ve learned that the majority of us have been conditioned to believe that genius is something far beyond our reach. It’s amazing how few of us believe we actually possess genius—yet nearly everyone believes it’s the secret ingredient of self-fulfillment and success in life and in business.

Let’s take Bill, for example. He was a successful investment banker who had been laid off from his firm and decided he wanted to do something completely different with his life and career. During our first session together, I asked Bill what his definition of genius was, and he answered, “Genius is about good genes, and unfortunately, I didn’t get any genius genes.” In his opinion, genius was an all-or-nothing proposition—either you have it or you don’t. Unfortunately, it’s an opinion that many of us share.

The problem with the commonly accepted concept of “genius” is that it’s a quality—like creativity—that has a magical, elusive connotation. Most people consider genius to be a gift, a lightning bolt from the gods that strikes a lucky few like Mozart or Einstein, but not the rest of us.

I’m here to tell you that this is simply not true. Every one of us has the capacity for genius. Any one of us could achieve or discuss or express something so extraordinary that it could change the world. More important, it could change

your

world.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that there’s an Isaac Newton or a Leonardo da Vinci deep inside us, just waiting to be discovered.

It means that when you are a fully realized person—authentic and entirely visible to the world—you are capable of exceptional accomplishments in your work, in your community, and among your friends and family.

It means that

you

are the genius, operating not necessarily in the lofty, exclusive heights of science or culture but right here, right now. It’s the kind of practical, street-level, everyday genius that can change the game for you, your business, and every aspect of your life.

But if genius is such a game changer, why does the concept of genius seem so alien to our experience? Why have we been programmed to believe that this gorgeous word can be applicable only to a select few who have been blessed with a rare, extraordinary talent?

In 2008, I had one of those life-changing experiences you usually see described on

The Oprah Winfrey Show.

Like more than 20 million people before me, I decided to have corrective eye surgery after having grown tired of wearing glasses or contacts for most of my life. So many people I knew raved about this surgery—you know, “Gina, it’s a piece of cake” or “Gina, you will wake up the morning after and will finally be able to see the alarm clock without your glasses.”

The stories I

didn’t

hear were about the common risks associated with the surgery. I didn’t bother to research or investigate them either. I honestly could not be bothered with the details; all I cared about was the end result—no more glasses, no more annoying contacts, nothing but blue sky (that I would be able to see

really, really clearly!

) ahead.

Over the course of the evening after my surgery, I developed an infection. Only one in twenty-five thousand patients gets this particular kind of infection, which results in severe inflammation—and I happened to be one of them. And instead of waking up to that alarm clock experience everyone had predicted, the day after what should have

been routine surgery I opened my eyes to... nothing. What followed was three days of darkness, certainly the longest three days of my life.

That temporary blindness was as terrifying and painful and deeply disturbing as anything I’d ever experienced. But it also brought the most profound, life-changing insight of my entire life.

The sudden loss of sight placed me in a kind of heightened reality chamber. It was as if I had been given a truth serum, only the truth was being revealed to myself. Though I had very little sight during those days, I could suddenly see one thing very clearly: that I could no longer continue with my traditional job and my existing life.

Not that my working life was so bad. In fact, it was pretty great by most standards. I’d been working in corporate America for more than a decade, rising to great heights in positions at Avon and PR Newswire. I had a great office and nice suits, and I made a healthy salary. From the outside, I looked successful and happy.

But something was missing. While I had been working myself to the bone every day in the office for the last decade, I felt I was hiding a big part of myself—the most important part, my creativity and passion—deep inside. Eventually, I was so stressed out at the prospect of starting my workday that I literally made myself sick. Just about ten months before my scheduled eye surgery, I had been diagnosed with shingles (which, if you’ve never had it—lucky you).

Shingles is brought on by stress.

How the hell could I end up in the hospital with the shingles over work?

I asked myself at the time. Work that I didn’t even love doing anymore. How did this happen? Why? For what reason did I allow myself to get to this miserable moment?

During the days I spent in darkness, I began to see in great detail the actualization of the career I’d always dreamed of, which was to coach and write. Despite this terrifying experience—coupled with the very grim economic reality of the moment (Wall Street had just collapsed, and the rest of the country was rapidly following it down into the sinkhole)—I knew I had to make a dramatic change in my life.