Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power (19 page)

Read Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power Online

Authors: Steve Coll

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #bought-and-paid-for, #United States, #Political Aspects, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Business, #Industries, #Energy, #Government & Business, #Petroleum Industry and Trade, #Corporate Power - United States, #Infrastructure, #Corporate Power, #Big Business - United States, #Petroleum Industry and Trade - Political Aspects - United States, #Exxon Mobil Corporation, #Exxon Corporation, #Big Business

Yet, the environment in which ExxonMobil and the Bush administration devised parallel approaches to managing science and public policy in the age of oil spills and global warming was influenced by several factors that Darwin would not have recognized. One was the prominence of lawyers and their win-for-the-client mind-sets. The tobacco industry’s near bankruptcy had demonstrated that not even talented lawyers could overcome terrible facts in a product liability matter. Yet that example had also shown how industry funding and purposeful, subtle campaigning could profitably delay a legal reckoning for a dangerous product through the manipulation of public opinion, government policy, and scientific discourse.

The scientific facts about oil pollution and climate change that ExxonMobil and its political and intellectual allies in Washington had to manage as the Bush administration took office were nowhere near as daunting as those that confronted the tobacco industry when the dangers of smoking were publicly recognized in the early 1960s. By comparison, the public health effects from the burning of fossil fuels were often indirect. The American economy’s dependence upon oil and gas was not the product of some clever marketing campaign, as cigarette smoking arguably was, but was embedded in technological and industrial evolution.

When regulators or lawsuits challenged ExxonMobil’s liability on environmental matters, the corporation turned fiercely combative—Irving’s internal protocols provided for rapid intervention by ExxonMobil’s law department, which spent large sums on the most talented and aggressive outside litigation firms. “They took a very hard line on the legal issues,” explained a member of the corporation’s board of directors. “It’s very much a take-no-prisoners culture.” From Washington to Houston to capitals worldwide, ExxonMobil executives internalized the corporation’s attitude toward lawsuits of all kinds: “We will not settle just to avoid a struggle; if we believe we are in the right, we will use our superior resources to fight and appeal for as long as possible, and when the case is over, your house may no longer be standing. Think twice before you take us on.” ExxonMobil’s spokespeople and lobbyists regularly expressed dismay that the scientific findings they presented about the

Valdez

cleanup, climate, chemical regulation, and other public policy issues were not accepted by journalists, judges, and politicians as fully credible.

David Page knew that the government scientists thought of him as a corporate shill, and he felt insulted by that accusation. “It’s not about corporate America,” he said. “To compare Exxon to a tobacco company is totally outrageous. They are two very different things. I will tell you, my livelihood was teaching students chemistry and biochemistry. I didn’t need to work for Exxon or anybody else. If I thought for a minute that I was being asked to say something that wasn’t true or to hide information or act in [an] indefensible way at all, I would have taken a hike and not had any further relationship. I don’t hold my nose when I’m talking.”

Jeffrey Short ultimately quit his government job in part because of the distractions caused by the corporation’s unrelenting Freedom of Information Act requests. “We’re all scientists—we didn’t sign up to do that,” he said.

Mandy Lindeberg could think of only one positive aspect of her experience as an ExxonMobil adversary. Knowing that every field note she and her colleagues made would be scrutinized by corporate litigators and scientific consultants, she said, “forced us to be very good scientists.”

15

Six

“E.G. Month!”

E

quatorial Guinea seemed like a place that Gabriel García Márquez had invented, a former American ambassador once remarked.

1

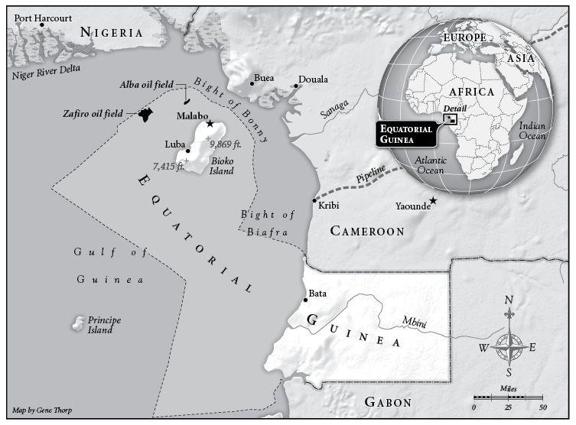

A thumbprint on the west coast of Africa, the entire country consisted of an offshore island, where the capital of Malabo was situated beside a cliff-walled harbor, and a sliver of land on the continental shoreline. It had been one of Spain’s few African colonies. In 1968, Generalissimo Francisco Franco, Spain’s then-septuagenarian dictator, granted independence to a government led by Francisco Macías Nguema, an anticolonial politician. Macías turned out to be a depraved mass murderer. He imprisoned, tortured, and killed his opponents by the score. He closed schools, campaigned against intellectuals, and burned boats to prevent his people from fleeing his realm. His security guards executed 150 people in a sports stadium on Christmas Day while loudspeakers blared “Those Were the Days.” In Malabo, Macías maintained an active torture chamber in Black Beach prison. He increasingly walled himself away on the slice of mainland Africa where his Fang ethnic group predominately resided. He descended into paranoia and lashed out at anyone who challenged him. Roughly a third of Equatorial Guinea’s small population would die or manage to escape during his reign.

2

On August 30, 1971, Lannon Walker, a diplomat at the United States embassy in neighboring Cameroon, telephoned his colleague Len Shurtleff to report signs of trouble emanating from the nearby American embassy in Malabo. Walker reported that Al Erdos, the American chargé d’affaires in Malabo, might also be going insane.

Erdos had been sending strange cables in recent weeks. Now he had come on the shortwave radio to report on some sort of Communist plot involving one of his American colleagues, whom he had tied up in a vault in the chancery. Walker asked Shurtleff to fly to Malabo to investigate. The diplomat arrived that evening by chartered aircraft. At the tiny embassy—little more than a rented house—Erdos, visibly distraught, pulled him aside. He announced, “I lost my cool. I killed Don Leahy.”

He was referring to the embassy’s administrative officer. Inside the chancery Shurtleff found scattered papers and spattered blood. A woman’s scream called him to an interior room. There he found Mrs. Leahy kneeling over the body of her dead husband. He had been stabbed to death with a pair of embassy scissors.

An autopsy showed that Leahy had semen in his trachea, suggesting that love or sex had been an issue between murderer and victim. At his subsequent trial in a Virginia federal court, Erdos entered an insanity defense; his lawyers blamed Equatorial Guinea’s menacing tropical dictatorship for having driven him mad. The jury convicted him of manslaughter.

3

The case established a tone in U.S.–Equatorial Guinean relations that would persist for years to come. The host government accused one of Erdos’s successors of sorcery and expelled him; the ambassador in question, John Bennett, had persistently raised concerns about the country’s human rights record. The United States shut its Malabo embassy, pleading budget constraints. Thereafter it serviced Equatorial Guinea by airplane from its embassy and consulate in Cameroon.

E

quatorial Guinea was perhaps the most politically toxic oil property Lee Raymond had acquired from Mobil. Given Exxon’s reserve replacement challenges, however, it was hard to be picky. Resource nationalism in the Middle East had driven all of the Western majors to Africa in search of bookable reserves. Exxon had had success on its own in Angola, but Raymond would mainly be dependent on Mobil’s legacy properties if he wanted to share in Africa’s emergence after 2000 as an increasingly important oil play. Some of the contracts available to Western oil companies in West Africa, such as in Nigeria, could be restrictive. Equatorial Guinea was a case where the upside was more attractive, financially—as it had to be, given that, on the world’s political risk charts, the country presented an extreme case of uncertainty. By 2001, ExxonMobil operated oil platforms about forty miles offshore, where workers on four-week rotations pumped steadily rising amounts of crude—more than 200,000 barrels per day and rising, or about 8 percent of ExxonMobil’s worldwide production of oil and gas liquids that year. Mobil had negotiated a contract with Malabo’s inexperienced government in which it secured the right to recoup its investment expenses from oil sales in the early years of production, paying Equatorial Guinea’s government an initial royalty of only about 10 percent. The principle that Mobil should be able to recover its costs early was typical of deals designed to protect international oil companies from political risk, but these specific terms were favorable. Now oil prices were rising, and the project looked likely to pay off big to both parties.

4

ExxonMobil’s headquarters and residential compound in Malabo stood beneath a towering dormant volcano. A large population of monkeys inhabited the mountain’s rain forests; they were shy because humans had long hunted them as food. In the evenings heavy tropical clouds often skirted the volcano, which had two peaks, like a double-humped camel. Lightning flashes and quiet rumbles of thunder added to an air of ominous majesty. The ExxonMobil refuge contained stucco buildings with Spanish red tile roofs—residences, offices, and recreation facilities, including a swimming pool. It was not particularly luxurious—certainly not as comfortable as the burgeoning Marathon Oil waterfront compound across the bay, which housed more workers than ExxonMobil’s did and had been laid out for tennis courts, basketball courts, squash and racquetball courts, a clubhouse, and a restaurant. At night, Marathon’s gas flares and the white safety lights at its liquefied natural gas and methanol plants illuminated the dark water that spread out beneath ExxonMobil’s smaller facility.

The second-generation dictator who oversaw ExxonMobil’s inherited contract was Teodoro Obiang Nguema, a nephew of Macías’s and a brigadier general trained at a military academy in Spain. In 1979, Obiang had led an uprising against his uncle and seized power. He arrested Macías and assigned mercenary bodyguards to execute his uncle by firing squad.

5

“When I came to power, the place was completely destroyed,” Obiang remembered. “No electricity, no roads. The schools were closed.”

6

Few reliable statistics were kept for the country by its government or international agencies, but per capita income was perhaps one hundred dollars per year. Hunger stalked the forest villages, less than a third of the population had access to safe drinking water, mothers and babies commonly died in childbirth, and life expectancy was less than fifity years. Because of the depredations of the Macías years, the country’s cocoa economy, once modestly successful, no longer existed. Obiang settled into power in a less wanton but no less ruthless manner than his predecessor. He turned ministries, businesses, and land over to his family members and through them constructed layers of internal security, strengthened at the inner core by his palace guard of salaried Moroccan soldiers. Black Beach prison remained open, and the torture techniques of its jailers and political prosecutors did not much change, according to one human rights investigation after another.

Still, Obiang kept the United States satisfied about his foreign alliances. Unlike Macías, he sought to work as a professional authoritarian, in the manner of those who led neighboring nations in West Africa. At business meetings Obiang usually turned up in a dark, tailored suit with a pocket kerchief; he could be coherent, direct, and even sophisticated, if also persistently obtuse about the precepts of good government. To interact more successfully with his French-speaking neighbors, Obiang took on a French tutor at his palace. He played tennis regularly and jogged along the rutted, red clay road between the airport and Malabo’s elegant but water-streaked colonial plazas. He danced through the night at parties and drank copiously.

7

He developed cancer and eventually traveled to the United States about four times a year for treatment. The scope and seriousness of the disease was a closely guarded secret, but Obiang, as rugged as a crocodile, seemed to overcome it. His regular medical travel to the United States and a deep antipathy toward France and Spain turned him gradually into an unrequited friend of America’s. Oil, he hoped, might persuade Washington to embrace him.

Equatorial Guinea’s territorial ocean waters encompassed some of the same geology that had much earlier enriched Nigeria and Gabon with oil dollars. Obiang provided exploration leases to Spanish oil companies during the late 1980s. It was relatively early in the development of offshore oil technology, and the Spaniards reported they could find nothing. “Thanks to the American embassy” in Cameroon, Obiang recalled, Joe Walter, an irrepressible Houston wildcatter, agreed to take a second look. In 1991, tiny Walter International discovered Equatorial Guinea’s first oil, in the Alba field. Obiang interpreted the news as evidence that Spain had deliberately suppressed his country’s economic potential, while the Americans seemed prepared to back him. Walter sold out its holdings as Mobil, Marathon, and Amerada Hess arrived to explore farther. Equatorial Guinea hired no outside lawyers or investment bankers to negotiate; Obiang’s first-ever oil minister, Juan Olo, worked out the terms. Mobil acquired rights to the offshore Zafiro field, which, as it turned out, contained at least a billion barrels, or at least three times Mobil’s entire annual worldwide production of oil and gas liquids in 1995.

8

Mobil embedded itself in financial partnership with the Obiang government; it paid for land, office leases, and security services. The local companies it worked with had many ties to the president and his family. Under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, it can be illegal for American companies to make sidebar payments to businesses controlled by foreign government officials who are at the same time handing out lucrative contracts for oil. In later years, the Department of Justice questioned Mobil’s deals with local firms, but ExxonMobil warded off the investigations by arguing that it had no alternative but to invest with the ruling family because there was no market for land or services that was not controlled by the Obiang clan. The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, as interpreted by Justice, did not hold that some countries should be avoided altogether, only that American corporations should not act corruptly if they had a choice in the matter. Some of Mobil’s and later ExxonMobil’s payments to Obiang’s regime covered scholarships for students and relatives selected by the president to study in the United States. The corporation also held a joint investment in a fuel services company; Obiang controlled the venture’s minority partner, a company called Abayak, according to the findings of a U.S. Senate staff investigation.

9

“The private American (especially oil) companies would not wish to be pulled into U.S.G. [United States government] efforts to combat human rights violations in Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea,” reported a U.S. embassy cable written just after Equatorial Guinea’s oil began to flow in earnest. “U.S. companies are aware of human rights violations . . . [but they] present themselves as ‘ahead of the curve.’”

10

That seemed mainly a euphemism for corporate strategies of hunkering down, avoiding publicity about human rights and other controversial aspects of Obiang’s reign, and staying as far away as possible from recurring State Department campaigns to reform Equatorial Guinea.

There were foreign policy episodes, such as in the Aceh war, when ExxonMobil leaned on State to intervene on the corporation’s behalf. Equatorial Guinea provided a different imperative: The Bush administration’s human rights campaigning in Africa was more likely to taint ExxonMobil in Obiang’s eyes than to help the corporation’s position as an oil contractor. ExxonMobil therefore adopted a low-profile posture of strict noninterference in Equato-Guinean politics, coupled with quiet advice to Obiang aimed at helping him improve his international reputation, which would redound to their mutual benefit.

Lee Raymond regarded the State Department as not particularly helpful to ExxonMobil, notwithstanding the example of the administration’s intervention to stop G.A.M.’s targeting of the corporation. America’s career diplomats did not understand international business very well, and some of them were outright hostile to large oil firms, Raymond believed. Where they did try to intervene in a commercial or contract matter, they often did not know enough detail to be constructive, and they did not appreciate the need for strict confidentiality, he concluded. Raymond could talk from time to time with his friend Vice President Cheney, who understood his issues, but the ExxonMobil chief executive had come to the view that as for the American foreign policy and government bureaucracy in general the best approach was, as he told his colleagues, “Don’t talk to them.” That did not mean ExxonMobil never asked State for favors; it meant only that the corporation’s demands for Bush administration intervention were erratic, inconsistent, and influenced by Raymond’s access to back channels with Cheney and other officials he regarded as sophisticated and reliable, such as Samuel Bodman, who would become secretary of energy during President Bush’s second term. ExxonMobil and its handful of international American peers in the international oil industry “blow hot and cold,” the veteran American diplomat John Campbell wrote in one cable to Washington from West Africa. “For the most part [they] prefer to try to address industry-specific issues themselves. They may turn to the [State Department], only to back away from requests on further consideration. If their efforts fail to achieve a resolution or problems become more acute, they can quickly return demanding action.”

11