Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power (54 page)

Read Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power Online

Authors: Steve Coll

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #bought-and-paid-for, #United States, #Political Aspects, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Business, #Industries, #Energy, #Government & Business, #Petroleum Industry and Trade, #Corporate Power - United States, #Infrastructure, #Corporate Power, #Big Business - United States, #Petroleum Industry and Trade - Political Aspects - United States, #Exxon Mobil Corporation, #Exxon Corporation, #Big Business

Because of ExxonMobil’s appeals, the

Doe

case wound its way toward the United States Supreme Court. ExxonMobil retained the prominent Supreme Court advocate Walter Dellinger and the well-known white-collar defense lawyer Theodore V. Wells Jr. to represent the oil corporation. The Supreme Court asked the Bush administration for an opinion about whether it should take on the appeal. The issue fell to the administration’s solicitor general, Paul Clement. His office invited the two sets of lawyers to separate informal meetings at the Justice Department.

Collingsworth had by now moved into a new private firm. One of his partners, Bill Scherer, was a Florida Republican who had helped President Bush during the 2000 vote recount. Scherer believed in the human rights agenda behind the Aceh case and sought out a meeting at the White House to put in a word for his partner’s cause. He met in Washington with one of Karl Rove’s successors on the political side of the West Wing. His White House interlocutor heard him out and then told him, straightforwardly, “That’s up to Dick Cheney.”

15

In a reception area at the solicitor general’s office at the Justice Department, on Pennsylvania Avenue, Agnieszka Fryszman and her team waited for their session with Clement. The intimidating figures of Dellinger and Wells emerged—they had gone first and had just completed their presentations on ExxonMobil’s behalf. “They are grinning, laughing,” one of the participants recalled. “They think their meeting has gone really well. They’re high-fiving each other, popping champagne bottles—not literally, but you can tell they’re going out to celebrate.”

Fryszman’s team found their meeting to be a tough grind. They were interrogated about their anonymous clients, particularly about whether there was really enough evidence to withstand scrutiny if the case went forward. The human rights lawyers were impressed by the quality of the government interrogators, but they had no confidence about how the decision would come out. They went out afterward and knocked back shots, trying to keep their spirits up.

16

They soon had reason to be joyous: Clement decided against ExxonMobil and told the Supreme Court that there was not enough at stake in American foreign policy to justify extraordinary action by the high court. Time had changed the Bush administration’s thinking about the balance of American interests in Indonesia: During the long delays in the case, not only had the Aceh war been settled, but Indonesia had evolved toward stable democratic politics and was enjoying rapid economic growth. The country could now afford scrutiny of its past human rights problems; such a trial might even strengthen its democracy.

Judge Oberdorfer suffered a stroke shortly after Clement’s decision. He prepared to retire. As he recovered from his illness, he composed an opinion ordering the

Doe

case to trial, one of the last written decisions of his career. He came out on the side of the Does. “Plaintiffs have provided sufficient evidence, at this stage, for their allegations of serious abuse,” the judge concluded.

17

ExxonMobil appealed again. Its lawyers had outlasted Oberdorfer. A new judge might see the issues differently. In Aceh, among the original eleven Does, two more of the plaintiffs died as the appeals went on, leaving widows and estates to pursue their claims.

Nineteen

“The Cash Waterfall”

I

n Hugo Chavez’s Venezuela, ExxonMobil’s strategy for attracting goodwill in the midst of political contention relied on the powers of art. The corporation staged a salon exhibition in Caracas at regular intervals, with prizes for the best work. It held the event at the National Art Gallery on the Plaza de los Museos. A serene, neoclassical building housed the gallery on grounds that contained a manicured interior courtyard, weeping willows, and a small pond. Tim Cutt, an American who served as the president of ExxonMobil’s Venezuela operations after 2005, presided over the exhibitions with the careful decorum of a museum curator who must please donors and patrons of impossible quirkiness and diversity. The tone Cutt and his colleagues sought to convey at the events was,

The art speaks for itself; it brings us all together

. In Venezuela’s eroding democracy, however, that wish proved increasingly difficult to fulfill.

The trouble began as the 2006 presidential election approached. The long struggle between President Hugo Chavez and his opponents intensified. A son of schoolteachers, Chavez had enrolled in a military academy as a young man, played baseball, wrote poems, fought in counterinsurgency campaigns, and rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel. During the 1980s, he became involved in leftist movements seeking to challenge Venezuela’s business and landed elites for power; with his red beret and fiery rhetoric, he emerged as a populist leader. He was jailed for his role in a 1992 coup attempt and later won the presidency by promising to restructure Venezuela’s corrupt, inequitable economy for the benefit of the poor. Once in office, he acted with increasing ruthlessness to consolidate power. Democratic, civic, business, and military forces opposed him.

Venezuelan artists seized on the annual ExxonMobil exhibition at the National Art Gallery as a forum for dissent: They submitted to the contest only paintings oiled in black, with the map coordinates of Venezuela, from west to east, lightly etched on the dark canvases. ExxonMobil’s Caracas executives decided they had little choice but to mount the stark paintings all around the gallery.

The artists demanded the microphone at the exhibition’s opening. The corporation’s mortified local public affairs team negotiated an agreement to let them speak briefly; Tim Cutt yielded the floor. The artists explained one after the other that their paintings depicted the future of Venezuela under Hugo Chavez: It would be bleak, they said, in case anyone missed the symbolism of their canvases. They denounced the president and his encroachments on civic freedoms. ExxonMobil’s executives nodded politely.

This was the sort of awkwardness that had persuaded the corporation’s engineer executives to steer clear of politics in the countries where they worked, and to concentrate as narrowly as possible on those issues that enabled oil and gas production. Now ExxonMobil had opened the door to art-as-politics and there was little the Caracas office could do to reverse course, its local executives believed. If they canceled the next contest, they would signal fear or, worse, that ExxonMobil was somehow choosing sides in Venezuela’s polarized polity. It was not clear whether Chavez or his opposition would prevail across the long arc of years by which ExxonMobil measured geopolitics: As recently as 2002, the president had barely survived an uprising and coup attempt.

Once the ExxonMobil art wars were launched, the Chavez regime acted decisively: It dispatched its own cadres to the next corporate salon. The Chavez loyalists took the floor and delivered pointed speeches against Yankee imperialism. There was nothing the ExxonMobil executives could or would do to stop them; the National Art Gallery was state owned, and these were Venezuelan government representatives. Cutt and his aides reported the incident to their supervisors at the ExxonMobil upstream division in Houston. Their shared conclusion, said a former executive involved, was that “this is going to be harder and harder to handle.”

1

E

xxonMobil had multiple interests in Venezuela: downtream filling stations, some oil production ventures, and supply agreements that directed Venezuelan oil to a large refinery in Chalmette, Louisiana, which ExxonMobil owned jointly with Venezuela’s state-owned oil company. The web of contracts, financing agreements, and supply linkages meant that confrontation with Venezuela’s leader could prove unusually messy and costly. The dependency was mutual: Venezuela’s oil was unusually sour, not suitable for most refineries worldwide, whereas the Chalmette facility was tailor-made to handle it profitably. Moreover, as the U.S. embassy noted succinctly, “Chavez’s priority is regime survival.”

2

He needed oil royalties, profits, and taxes—the principal source of revenue for the Venezuelan treasury—to pay for expanded social spending born of his self-styled Bolivarian revolution. After the failed 2002 coup attempt, Chavez signaled in speeches and rambling television interviews that he intended to take greater control of Venezuela’s oil industry, to challenge what he described as the dominance of foreign profiteers. Yet some of ExxonMobil’s executives calculated that the president could not afford to spook international oil corporations precipitously or to trigger even more capital flight from Venezuela than was already taking place in response to the president’s policies.

As Chavez gathered power and increasingly employed the populist rhetoric of resource nationalism to stir his followers, ExxonMobil responded initially with appeasement. During 2004, Chavez came under intense pressure from the democratic opposition, a wave of resistance that culminated in the scheduling of a referendum in August of that year to determine whether he could continue in office. Part of the charge against him was that he was jeopardizing Venezuela’s economy through his rash, irrational, corrupted populism. Chavez pressured the international oil companies in Venezuela to sign and publicize agreements with his regime on the eve of the election. Televised signing ceremonies would signal confidence in his presidency by bastions of global capitalism. ExxonMobil had been talking with successive Venezuelan governments for nine years about a multibillion-dollar petrochemical investment that would supply plastics to Latin America’s burgeoning economies. It had never been able to close even a preliminary deal. Now Chavez volunteered to sign an initial understanding—if ExxonMobil would agree to a televised signing ceremony three days before the referendum vote, effectively handing Chavez the American corporation’s endorsement.

The Bush administration sought to contain Chavez and hoped democratic forces would overthrow him peacefully. The referendum was a critical moment. The administration tried not to undermine Chavez’s opposition by embracing them openly, but there was no question which side of the vote Bush was on. ExxonMobil’s executives understood perfectly that the administration would prefer them to take no steps that would strengthen Chavez on the eve of a critical vote about his legitimacy and tenure in office. On the other hand, here was a long-sought investment opportunity finally on offer. The corporation capitulated to Chavez. It agreed to a televised signing ceremony just three days before the election.

Charles Shapiro, Bush’s ambassador in Caracas, asked an ExxonMobil executive why the corporation would accept such a clearly supportive contract signing on the eve of an “event that has convulsed Venezuela’s political life.” The executive replied that ExxonMobil “could not think of any other issues to raise” with Chavez’s government in the contract negotiation, and the Venezuelans had been “pressuring the company [to] sign immediately.” Lee Raymond, then ExxonMobil’s chief executive, telephoned the Bush White House to tell them of his decision. His deputies in Venezuela signaled that Raymond might be willing to meet Chavez personally if the petrochemical talks advanced far enough. Amid fraud allegations, Chavez won the vote.

3

The peace ExxonMobil purchased that summer did not last. Politics, not the maximization of profit, drove Chavez’s thinking about Venezuela’s oil industry. Reasserting Venezuelan control over the country’s oil was for Chavez an irresistible opportunity. As his assaults on the contract terms enjoyed by the international oil majors intensified, ExxonMobil’s executives and lawyers decided that this time, they would not give in. They also decided to maximize Chavez’s pain. They concocted a legal ambush—carried out, in its final act, on a wintry Friday afternoon in the Manhattan offices of a prestigious law firm—to seize by stealth more than $300 million in cash from the fiscally strapped, debt-laden Venezuelan regime. It would be one of the largest asset seizures ever attempted by an American oil corporation. The Bush administration struggled to punish Chavez for his anti-American policies in a way that measurably pinched him. ExxonMobil, when it finally aligned with the administration’s perspective, developed a practical scheme. The corporation’s motivations were pecuniary—the interests of its private empire, not the policies of President Bush, provided the cause. The plan involved a mechanism of modern global finance known to its participants as “the cash waterfall.”

E

xxon had been thrown out of Venezuela once before, in 1975, when the country’s elected government embraced the global trend of oil nationalizations. (Venezuela’s government claimed its intervention was not a full expropriation, but Exxon insisted that it was, and the American government backed Exxon up as the company fought for compensation.) To ease Exxon’s departure, Venezuela cut some unpublicized sidebar deals, an American official and a former Exxon executive said later. The state-run oil giant, Petróleos de Venezuela, known by its acronym, P.D.V.S.A. (pronounced as “peh-de-vay-suh”), allowed Exxon to purchase Venezuelan oil at discounted rates, for refining and onward sale.

Nationalization had proven to be disastrous for the Venezuelan oil industry the first time around. P.D.V.S.A. had many outstanding engineers and executives educated at international universities, but under political control the state-run company could not acquire the capital and technology required to maintain oil production. Venezuela’s oil output fell by more than half, from 3.7 million barrels per day in the mid-1970s to just 1.8 million barrels per day by the mid-1990s.

Falling global oil prices also played a role in the industry’s collapse, in part because much of Venezuela’s oil was “extra-heavy,” meaning it was laden with sulfur, acid, salt, and heavy-metal contaminants. (An industrywide system developed by the American Petroleum Institute designated oil as “light,” “medium,” “heavy,” or “extra-heavy,” on a scale that, among other things, compared the density of a particular batch of oil with the density of water; extra-heavy oil was denser than water. The A.P.I. scale used numerical degrees to describe grades of oil, ascending from heaviest to lightest. Extra-heavy oil was less than 10 degrees, whereas light or “sweet” crude, the most suitable for refining, could be as high as 48 degrees. Oil rated higher than 31 was labeled “light.”) Heavy oil required extra production steps to prepare it for sale. Among other problems, the oil did not flow smoothly in its natural form. The costs of these additional processes meant that most heavy and extra-heavy oil could be extracted profitably only when global oil prices were high. P.D.V.S.A. lacked the technologies to produce Venezuela’s reserves economically as prices fluctuated at low levels during the 1980s and 1990s.

Venezuela reversed its attitude toward outside corporate oil investment as the cold war’s end spurred privatizations worldwide. The country’s oil-dependent economy had long stagnated, and rates of poverty had risen, in line with the grim forecasts of resource curse theorists. To generate more revenue for development, the government opened talks with international oil companies about deals that would allow foreign ownership of Venezuelan crude again, through joint ventures with P.D.V.S.A.

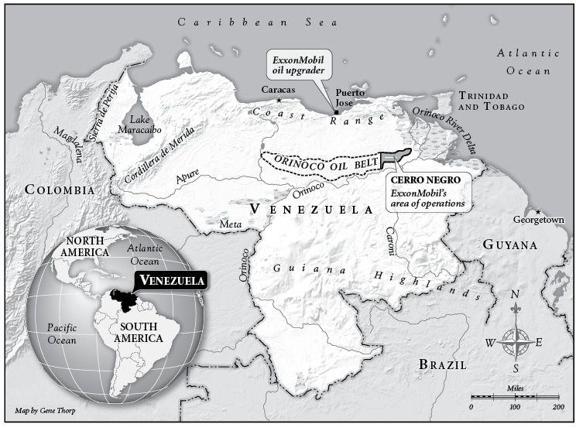

Some of the deals involved the country’s rich, underdeveloped vein of extra-heavy oil, in the Orinoco River Basin, which lay in Venezuela’s wet coastlands to the east, near Guyana. The Orinoco River snaked thirteen hundred miles to the Caribbean through tropical palms and slash-and-burn agricultural fields. The United States Geological Survey estimated that the basin held between 380 billion and 650 billion barrels of recoverable oil, perhaps double Saudi Arabia’s endowment. This vast reserve lay beneath the river basin’s muddy soil, but the petroleum was unusually viscous and contaminated. American, Canadian, and European oil companies had begun to experiment by the late 1990s with new technologies that could efficiently “upgrade” heavy oil near wellheads and refine it to a lighter blend, suitable for international markets. Mobil was a leader in the field. Its executives opened talks with Venezuela’s oil ministry about an Orinoco heavy-oil project in 1991 and finalized a contract six years later. The deal was known as the Cerro Negro Association Agreement. (There were four such associations created to mine Orinoco’s reserves. Total of France, Statoil of Norway, ConocoPhillips, Chevron, and BP all participated, either as operators or as minority holders.)