Project Best Friend (7 page)

Penelope didn’t much like the reference to tantrums. She preferred to think of what had happened as an outburst. Still, it was kind of Bob to understand that she was trying her best on the tour (which was difficult with the other girls barging in and being silly). And it was even kinder of Bob to stick up for Penelope – especially to Rita.

‘Yeah, she’s really nice,’ came Tilly’s voice. ‘Last week she gave me half of her lunch when I forgot mine. And she patted my back when I thought I was going to throw up after the cross-country run. She just does a wobbly-chuck every now and then.’

‘Well,’ Bob said, and Penelope thought she could hear a smile in her voice, ‘out of ten, I’d give that wobbly-chuck a five. I’ve done way, way worse. Once I squished a sandwich in a boy’s face because he called me stupid. A jam sandwich. Now

that

was at least a seven.’

The girls laughed again. Penelope wasn’t keen on the term ‘wobbly-chuck’ either, but she was beginning to feel much, much better.

‘Besides,’ Bob continued, ‘we all do stuff like that sometimes.’

Rita piped up again. ‘In year two, some kids were mucking around and they spilled juice on Penelope’s work. She went bright red, and didn’t say anything for the rest of the day!’

Penelope wondered if Rita had actually written a list of all her outbursts over the years, or if she’d stored them all up in her head.

‘That’s actually so true, Bob,’ Tilly said. Penelope was pleased that Tilly was ignoring Rita’s comment. ‘Like, for instance, you have a bad temper too, don’t you Jo? Remember when you screamed your head off at the boys because they won that netball match?’

‘Yeah, and when you’re mad you go all sooky, Tilly,’ Joanna replied. ‘You bawled your eyes out that time Felix knocked your arm and you dropped your pink doughnut in the dirt!’

‘I just have overactive tear ducts,’ said Tilly, but she sounded amused, rather than cross. ‘Anyway, that was

years

ago.’

‘It was

last

year,’ Joanna replied with a giggle. ‘Boo hoo.’

‘See?’ Bob said. ‘What Penelope did wasn’t a big deal.’

‘Right,’ came Tilly’s voice.

‘Penelope also had a major meltdown in …’ But Rita’s voice trailed off as the others all agreed with Bob.

‘Yeah, of course it wasn’t,’ Joanna said.

‘It so wasn’t last year, Joanna,’ Tilly continued. ‘And stop sticking your tongue out. It’s disgusting.’

Penelope could hear Joanna’s giggle getting smaller and smaller as the girls left the toilets. She snuck a peek under the door to check there was no-one left. Then she left the cubicle and tidied her ponytail in front of the mirror, smiling at her ref lection. Bob was absolutely going to be the greatest best friend in the whole world.

All she had to do now was to keep following Grandpa George’s advice.

As Penelope had expected, going with the flow was very difficult. At recess, she found herself sitting at the benches in the courtyard (frying in the hot sun) rather than under the shady tree, because most of the other girls (including Bob) were on the benches too.

Things were back to normal. The girls were so full of chatter that Penelope hardly got a word in. Ordinarily, Penelope would have forced her way into the discussion, even if it was about Rita’s boy band, or some silly crush Eliza had.

But today, especially after what happened in the girls toilets, Penelope was determined not to force anything.

At lunchtime, going with the flow was almost impossible. Joanna (the naughtiest girl in the class) had brought water balloons to school. She filled them up at the taps and tossed them randomly at people, which was definitely against school rules.

Penelope stood at the top of the hill and watched. Sarah was the first girl to be water-bombed. She was running away from Joanna, so Penelope could only see her back. But even from a distance, Penelope could see the mark it made on the back of her dress. Penelope held her breath as she saw Sarah’s shoulders shaking, but when Sarah turned around, she realised the shaking was from laughter.

So, they were having fun. Nobody was getting hurt. And water was just water. It wouldn’t leave a stain.

Penelope remembered to breathe. This was the correct way to think when you were going with the f low. As another water bomb exploded in Alison Cromwell’s hair, Penelope didn’t even hold her breath. There may have been an extra-long blink, but that was all. And even though the teacher on yard duty, Mr Joseph, was

supposed

to be aware of what was happening in the playground, but had no idea (just like the day Penelope had earned her ‘Watchful Eye’ award), Penelope didn’t say a word to him.

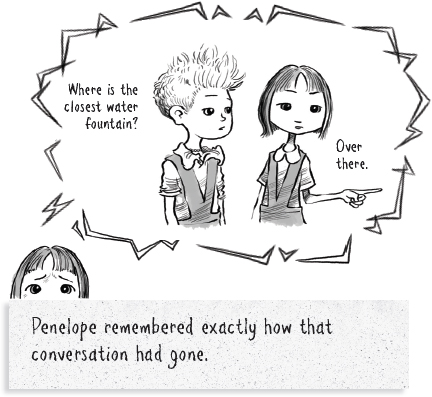

By the time the school day had finished, Penelope had spoken with Bob exactly once.

Even if Bob did think Penelope was nice, and even though she had stuck up for her in the toilets, Penelope doubted that this conversation could, in any way, be considered the beginning of a very special friendship.

Every Tuesday night (even after her daughter had a rather difficult and very complicated day) Penelope’s mother went to Zumba class, so dinner was make-your-own. Penelope looked through the shopping bags on the kitchen bench. She was pretty sure that microwave macaroni and cheese wouldn’t fulfil the requirements of the food pyramid. But she could put some carrots on the side, though she was almost certain that Harry (who was upstairs on his computer) wouldn’t eat them.

Penelope was putting the groceries away and thinking about her very complicated day when she felt something oblong and hard underneath the last brown paper shopping bag.

Penelope lifted the bag up. Then she gasped, because what was under the bag was entirely the sort of thing to inspire a gasp. It was a proper gasp, too, where her mouth opened into an O and then she clapped a hand over it.

Right there, on the bench in front of her, was an

entire tin

of fifty-two Derwents. It was brand new, still with the plastic covering. On top of the tin of fifty-two Derwents was a yellow sticky note with her mum’s scribbly writing on it.

Hey Poss,

I hope your day went OK.

Mum x

Penelope clutched the Derwents to her chest where she was quite sure her heart was. The tin felt cool against her school dress.

A little tear blurred her vision for a moment, but not because she was sad.

On Wednesday morning, before her mum got up, Penelope slipped a very lovely and very Derwent-colourful picture under her door.

Wednesday went pretty much the same way Tuesday had. So did Thursday. There always seemed to be a crowd around Bob, and Penelope hardly got a chance to talk to her. Penelope was seriously beginning to wonder if going with the flow was going to work.

It was a relief to stay back after school on Thursday to help Ms Pike prepare for their monthly session at the aged care centre down the road. Penelope loved going there. Sometimes the children would sing a song. Other times, someone would recite a poem.

At the last performance, Joanna had, unexpectedly, done a very nice job with

The Man from Snowy River,

which had made two of the elderly folk tear up.

For their visit on Friday afternoon, the class was going to perform a lovely bright song that Mrs Raven, the music teacher, had taught them called

Love and Marriage.

Penelope had noticed that Bob was a quick learner. She knew all the words already, even though she’d missed most of the rehearsals.

Penelope suspected that some of the boys (not Oscar) were

deliberately

forgetting the lyrics. She had suggested a solution to Ms Pike, and was now writing the lyrics, very clearly, on a large piece of cardboard so there could be no excuse.

It was very pleasant sitting in the classroom alone with Ms Pike. Ms Pike’s voice was lovely as she dictated the words. Penelope particularly liked the line,

they go together like a horse and carriage.

She liked the idea of things going together so neatly.

Penelope couldn’t help worrying about who she would end up partnering with on the way to the aged care centre. Going with the f low was taking an exceptionally long time to work, so it clearly wouldn’t be with Bob. If it had to be a boy (which had happened before), she hoped it would be Oscar. But with each moment she spent with Ms Pike, Penelope felt calmer and more settled.