Proud Highway:Saga of a Desperate Southern Gentleman (54 page)

Read Proud Highway:Saga of a Desperate Southern Gentleman Online

Authors: Hunter S. Thompson

The reason I sounded so uncertain on the phone the other night is that I feel that I'm plotting to cast off a son and my mind balks at the necessity

of doing it with a cool and reasonable head. I've become very attached to Agar and I hate the idea of giving him up. I can't take him to Europe, however, so I will have to do something with him by January 1, when I plan to leave for New York.

I wrote Mr. Baumgartner, asking for suggestions, and he gave me your name, saying you'd be happy “to see” Agar because he was out of your line. [â¦] In a nutshell, I suppose I should sell Agar. I've considered boarding him, lending him, leaving him with my family, but all these would work to Agar's disadvantage. So, rather than try to hang onto him in some uncertain way, I think I should sell him into a home where I'm sure he'd be happy. Since he's used to being treated more like a human than a dog, this would rule out most of the people who would answer an ad if I placed one in the paper. Most people seem to think all Dobermans are crazy mean and should be kept chained and muzzled. Agar is not that way and I wouldn't sell him to anyone who might treat him like a vicious criminal.

So, if you know of anyone who would like to buy Agar, I'd appreciate hearing from you. I think anyone I'd locate through you would be all right. As a last resort, I will either take or send him back to the Baumgartners. Since I took him out of a good home, I feel an obligation to see that he gets another one when I have to give him up.

Other salient items: I bought him for $100.00; since I know nothing about the Doberman market, I hesitate to put a definite price on him right now.

He has never been bred.

I have reason to suspect that he has a tapeworm. I have contacted a vet, who says an enema will cure it. Before getting this done, I wanted to talk to someone who knew Dobermans. Had you not been so rushed the other night, I'd have asked you about it. Agar shows no ill effects, but the day before I called you, what appeared to be a segment of a worm crawled out of him and gave me quite a shock. I had thought only puppies got worms. At any rate, I intend to take him to the vet in the next few days. If this is not the right thing to do, I'd very much like to hear from you and find out exactly what should be done.

He is very gentle and very restless. I run him about two miles a day behind the car to keep him in shape.

He is very intelligent and so obedient that I never cease to be amazed.

That's about it. You can reach me by phone at GL-1-xxxx, any time after noon. I look forward to hearing from you.

Sincerely,

Hunter S. Thompson

TO FRANK ROBINSON,

ROGUE:

Thompson pitched both a short story and an article on bluegrass music to

Rogue,

which turned down both. At the time Thompson was plotting to move in early spring to either London or Rio de Janeiro

.

December 22, 1961

2437 Ransdell Ave.

Louisville 4, Kentucky

Dear Mr. Robinson:

Here's another story you might like. I do. It's a much better (technically) story than the one you bought, different tone, not quite as dramaticâand a lot shorter.

Length seems to be a pretty salient point in this league. You people did a pretty fair job on that “Burial at Sea” business, but I can't quite figure your idea in ignoring all my letters. Doesn't make much difference, actually, but henceforth I'll be careful to send you my shorter stuff so I won't have to worry about having them trimmed down.

This one, I think, is pretty trim as it stands. Anyway, here it is.

One more thingâI'm doing a feature for the New York

Herald Trib

on a place called Renfro Valley, a sort of unpublicized Grand Ole Opry down in eastern Kentucky. I went down there to see what they thought about the current boom in Folk and Bluegrass music and got the word that I'd have a fight on my hands if I kept on using the term Bluegrass Music. Renfro Valley is very much in the Bluegrass region.

Seems it might be an interesting articleâmusic in the Bluegrass, as opposed to Bluegrass Music, Manhattan-style. The only real link seemed to be Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs, who once worked at Renfro, along with some people called the Coon Creek Sisters, from Pinch 'Em Tight Holler. Lot of interesting photos to be had down there, a good many novel ideas, decent home whiskey, and probably a worthy short article, mostly photos. Let me know what you think about it. I plan to bug off for New York in about ten days, so if you want something in that line, send a quick word.

That's about it for now.

Sincerely,

Hunter S. Thompson

“N

EW

Y

ORK

B

LUEGRASS

”

N

EW

Y

ORK

C

ITY

âThe scene is Greenwich Village, a long dimly lit bar called Folk City, just east of Washington Square Park. The customers are the usual mixture: students in sneakers and button-down shirts, over-dressed tourists in for the weekend, “nine-to-five types” with dark suits and chic dates, and a scattering of sullen looking “beatniks.”

A normal Saturday night in The Village: two parts boredom, one part local color, and one part anticipation.

This is the way it was at ten-thirty. The only noise was the hum of conversation and the sporadic clang of the cash register.

Most people approach The Village with the feeling that “things are happening here.” If you hit a dead spot, you move on as quickly as you can. Because things are happeningâsomewhere. Maybe just around the corner.

I've been here often enough to know better, but Folk City was so dead that even a change of scenery would have been exciting. So I was just about ready to move on when things began happening. What appeared on the tiny bandstand at that moment was one of the strangest sights I've ever witnessed in The Village.

Three men in farmer's garb, grinning, tuning their instruments, while a suave MC introduced them as “the Greenbriar Boys, straight from the Grand Ole Opry.”

Gad, I thought. What a hideous joke!

It was strange then, but moments later it was downright eerie. These three grinning men, this weird, country-looking trio, stood square in the heartland of the “avant garde” and burst into a nasal, twanging rendition of, “We need a whole lot more of Jesus, and a lot less rock-n-roll.”

I was dumbfounded, and could hardly believe my ears when the crowd cheered mightily, and the Green-briar Boys responded with an Earl Scruggs arrangement of “Home Sweet Home.” The tourists smiled happily, the “bohemian” elementâuniformly decked

out in sunglasses, long striped shirts and Levi'sâkept time by thumping on the tables, and a man next to me grabbed my arm and shouted: “What the hell's going on here? I thought this was an Irish bar!”

I muttered a confused reply, but my voice was lost in the uproar of the next songâa howling version of “Good Ole Mountain Dew” that brought a thunderous ovation.

Here in New York they call it “Bluegrass Music,” but the linkâif anyâto the Bluegrass region of Kentucky is vague indeed. Anybody from the South will recognize the same old hoot-n-holler, country jamboree product that put Roy Acuff in the 90-percent bracket. A little slicker, perhaps; a more sophisticated choice of songs; but in essence, nothing more or less than “good old-fashioned” hillbilly music.

The performance was neither a joke nor a spoof. Not a conscious one, anywayâalthough there may be some irony in the fact that a large segment of the Greenwich Village population is made up of people who have “liberated themselves” from rural towns in the South and Midwest, where hillbilly music is as common as meat and potatoes.

As it turned out, the Greenbriar Boys hadn't exactly come “straight from the Grand Ole Opry.” As a matter of fact, they came straight from Queens and New Jersey, where small bands of country music connoisseurs have apparently been thriving for years. Although there have been several country music concerts in New York, this is the first time a group of hillbilly singers have been booked into a recognized night club.

Later in the evening, the Greenbriar Boys were joined by a fiddler named Irv Weissberg. The addition of a fiddle gave the music a sound that was almost authentic, and it would have taken a real aficionado to turn up his nose and speak nostalgically of Hank Williams. With the fiddle taking the lead, the fraudulent farmers set off on “Orange Blossom Special,”

then changed the pace with “Sweet Cocaine”âdedicated, said one, “to any junkies in the audience.”

It was this sort of thingâhip talk with a molasses accentâthat gave the Greenbriar Boys a distinctly un-hillbilly flavor. And when they did a sick little ditty called, “Happy Landings, Amelia Earhart,” there was a distinct odor of Lenny Bruce in the room.

In light of the current renaissance in Folk Music, the appearance of the Greenbriar Boys in Greenwich Village is not really a surprise. The “avant garde” is hard-pressed these days to keep ahead of the popular taste. They had Brubeck and Kenton a long time ago, but dropped that when the campus crowd took it up. The squares adopted Flamenco in a hurry, and Folk Music went the same way. Now, apparently out of desperation, the avant garde is digging hillbilly.

The Village is dedicated to “new sounds,” and today's experiment is very often tomorrow's big name. One of the best examples is Harry Belafonte, who sold hamburgers in a little place near Sheridan Square until he got a chance to sing at the Village Vanguard.

Belafonte, however, was a genuine “new sound.” If you wanted to hear him, there was only one place to go. And if you weren't there, you simply missed the boat.

With the Greenbriar Boys, it's not exactly the same. I thought about this as I watched them. Here I was, at a “night spot” in one of the world's most cultured cities, paying close to a dollar for each beer, surrounded by apparently intelligent people who seemed enthralled by each thump and twang of the banjo stringâand we were all watching a performance that I could almost certainly see in any roadhouse in rural Kentucky on any given Saturday night.

As Pogo once saidâback in the days when mossback editors were dropping Walt Kelly like a hot, pink potatoâ“it gives a man paws.”

Â

Thompson in his study

. (P

HOTO BY

H

UNTER

S. T

HOMPSON; COURTESY OF

HST C

OLLECTION

)

Hunter with Dana Kennedy in San Juan

. (P

HOTO BY

W

ILLIAM

J. K

ENNEDY; COURTESY OF

HST C

OLLECTION

)

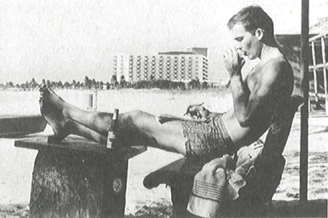

Thompson at work in Rio

. (C

OURTESY OF

HST C

OLLECTION

)

1

. A photographer who lived close to the Murphy house, who became a longtime friend and ally of Thompson's.

2

. Donald Maynard was a Big Sur/Monterey carpenter, handyman, and deliveryman.

3

. Mrs. Webb was a longtime Big Sur resident and a born-again Christian who ran the hot springs before Mrs. Murphy.

4

. Thompson had written Mailer on December 7, 1960, wondering why he hadn't attacked Nixon in print during the presidential election.

5

. The “little black book” was Henry Miller's

The World of Sex

, published privately by Miller in 1959. (Grove Press eventually published the book in 1965.)

6

. Willie Stark was the protagonist in Robert Penn Warren's

All the King's Men

.

7

. Lord was considered the “hot” New York agent at the time.

8

. Jay Gould was a late-nineteenth-century New York robber baron who owned railroads and the

New York World

.

9

. Major Frank Gibney was in the Office of Information Services at Eglin and contributed to the

Command Courier

.

10

. Pete Ballas was in charge of publicity for the

Command Courier

.

11

. Thompson made up this quote just to tease Kennedy.

12

. Fomento was Puerto Rico's news service/international development office.

13

. Claude Fink was a fictional character.

14

. Thompson is referring to William Styron's

The Long March

(New York: Vintage, 1957).

15

. Kennedy had sent Thompson back issues of the

San Juan Star

to assist him in writing “The Rum Diary.”

16

. Sontheimer was the head of the Puerto Rican News Service.

17

. Harold Lidin, the

Star

's correspondent, covered the events surrounding the assassination of dictatorial Dominican president Rafael Trujillo in 1961.

18

. Ann and Fred Schoelkopf were undergoing a brutal separation.

19

. Thompson had shot out his neighbor's windows with his .22 caliber pistol.

20

. Dick Price, who would become Michael Murphy's partner in the Esalen Institute.

21

. Denne Petitclerc, a

San Francisco Chronicle

reporter, was a close friend of William Kennedy's.

22

. Paul Semonin had gotten deeply involved in the civil rights movement and leftist politics. He was arranging to go to Ghana, to study firsthand the anti-imperialist movement of Kwame Nkrumah.

23

. Hudson was a first-rate sculptor known for making Alexander Calderish metal pieces. He became Thompson's closest Big Sur friend. Together they hunted wild boar and started building a sloop to sail around the world.

24

. Trotter owned land at Big Sur where he sometimes allowed Thompson and others to hunt wild boar.

25

. Ed Norman was the rural postman who would also deliver groceries on credit from Monterey.

26

. References are to childhood friends of Thompson's.

27

. Sports editor of the

San Juan Star

.

28

. Clifford lived in Aspen from 1953 to 1979, was a columnist for the

Aspen Times

for twelve years, and owned the local bookstore. She and Thompson later became close friends when he moved to Woody Creek.

29

. Smith Hempstone was a

Chicago Daily News

reporter whose pieces on Africa, published in the

Louisville Times

, caught Thompson's attention.