Purple Cow (17 page)

Of these top one hundred, seventy are brands that were valuable in this country more than twenty-five years ago. Of these brands, virtually all were built with heavy advertising on television, in magazines, or at retail. These companies grew their brands back when it was easy and cheap to do it the old-fashioned way. These brands maintain their lead, blocking newcomers who don’t have the same vacuum to fill.

Of the remaining thirty brands, half were built almost entirely through word of mouth (Hewlett-Packard, Oracle, Nintendo, SAP, Canon, IKEA, Sun, Yahoo!, Ericsson, Motorola,

Amazon.com

, Prada, Starbucks, Polo Ralph Lauren, and Armani). While some of these brands—like Lauren and Sun—spent heavily on print advertising, it’s pretty clear that without a remarkable product and significant word of mouth, they wouldn’t have acquired the value and cachet they now hold.

Amazon.com

, Prada, Starbucks, Polo Ralph Lauren, and Armani). While some of these brands—like Lauren and Sun—spent heavily on print advertising, it’s pretty clear that without a remarkable product and significant word of mouth, they wouldn’t have acquired the value and cachet they now hold.

That leaves just fifteen brands. Some, like Cisco Systems and Microsoft, acquired their value through market power (either by acquiring competitors or bullying them out of the way). Others, like Apple, used both remarkable advertising

and

word of mouth. That leaves only a tiny handful (Compaq, Dell, Nike, The Gap, MTV, AOL, and perhaps Nivea) that built their brands the old-fashioned way. I’d argue that MTV doesn’t really count since they advertised only on their own channel, which people found through word of mouth.

and

word of mouth. That leaves only a tiny handful (Compaq, Dell, Nike, The Gap, MTV, AOL, and perhaps Nivea) that built their brands the old-fashioned way. I’d argue that MTV doesn’t really count since they advertised only on their own channel, which people found through word of mouth.

Notice that just one of the companies on the list is the product of the last ten years of media excess. Only AOL was able to spend hundreds of millions of dollars and convert that investment into a valuable brand. All the other companies that tried, failed.

So the question you need to ask yourself is this: If only 6 percent of the most valuable brands used the now-obsolete strategy of constantly reminding us about their sort-of-ordinary product, why do you believe this strategy will work for you?

The big question is this: Do you want to grow? If you do, you need to embrace the Cow. You can maintain your brand the old way, but the only route to healthy growth is a remarkable product.

Brainstorms

While we can’t predict what’s going to be remarkable next time, we can realize that there aren’t too many unexplored areas of innovation—just unexplored combinations. Here’s an annotated checklist. With just thirty-four examples, it’s not complete by any means, but it might get your juices flowing.

While this checklist may elicit an “of course,” I wonder how many struggling products have actually been through this analysis. Is your most recent offering the

mostest

of any of these attributes?

mostest

of any of these attributes?

WHEN I WENT TO BUY SOME NEW TOOLS, I did something I almost never do. I went to Sears. Why? Because almost without exception, the people I like and trust who spend a lot of time with tools told me that I couldn’t go wrong with Craftsman. Why? Not because they’re beautifully designed or easy to use. Solely because they last a long time and are guaranteed forever. KitchenAid, on the other hand, has lost legions of sneezing bakers because the company decided to save money in the way they make their mixers. Online bulletin boards are filled with stories of frustrated people who quit the brand after going through three or four mixers. In both cases, the stories are based on remarkable durability (or the lack thereof).

THE OXO LINE of kitchen gadgets sells to people who don’t even cook. Why? Because these non-cooks have visited the kitchens of people who do cook. And those cooking sneezers (always open to something that would make their lives in the kitchen better) were delighted to show off their funky-looking (and very, very functional) carrot peelers, lime zesters, and ice cream scoopers.

WHY DID YAHOO! defeat AltaVista, Lycos, and Infoseek in the race to become the center of the Internet? And how did Yahoo! forget that lesson and let Google do it again? In each case, Yahoo! and Google had the same things going for them. Unbelievably simple interface (for the first few years of Google, there were only two buttons—and one of them was “I feel lucky”). Fast loading. No decisions. When people asked someone else where to go to get what they needed online, the recommendation was simple.

Here’s a great Google story I heard from Mark Hurst: It turns out that the folks at Google are obsessed with the e-mail they get criticizing the service. They take it very seriously. One person writes in every once in a while, and he never signs his name. According to Marissa Meyer at Google, “Every time he writes, the e-mail contains only a two-digit number. It took us awhile to figure out what he was doing. Turns out he’s counting the number of words on the home page. When the number goes up, like up to 52, it gets him irritated, and he e-mails us the new word count. As crazy as it sounds, his e-mails are helpful, because it has put an interesting discipline on the UI team, so as not to introduce too many links. It’s like a scale that tells you that you’ve gained two pounds.” (Yahoo! has more than five hundred words on their home page now.)

A LONG TIME AGO, Hertz and Avis grew their brands with TV and print advertising. Today, it’s too late for their competitors to catch up using the same technique. So National and Alamo struggle. Enterprise Rental Car, though, has an entirely different strategy. They’re not at the airport and they don’t cater to business travelers. Instead, they created a new Purple Cow—they’ll pick you up with a rental car when your regular car is in the shop or totaled in an accident.

Targeting this niche seems obvious, but the ability to be radically different has also made them profitable and fast-growing. Safe, it seems, is risky.

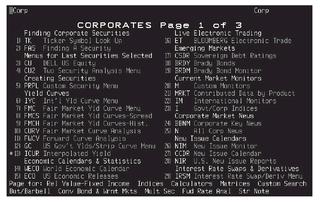

THE BLOOMBERG, AS IT’S KNOWN, should have been replaced by the Internet, yet this customized computer is on the desk of just about every important player on Wall Street. After all, the Net has access to huge amounts of information, it’s relatively easy to use, there are multiple sources for it, and it’s largely free. The Bloomberg, on the other hand, is very expensive (more than a $1,000 a month) and very tricky to use. And that’s why traders and other investors insist on it. They’ve gone through the pain of learning how to use it, and they’re not prepared to give up that expertise.

Other books

They Who Fell by Kevin Kneupper

Whisper to Me by Nick Lake

Reveal (Love & Beyond #2) by D. Griffith

Maverick Showdown by Bradford Scott

Rival Dreams (Rival Love #3) by Natalie Decker

Murder by Mocha by Cleo Coyle

Lure of the Wicked by Cooper, Karina

Slip of the Tongue by Jessica Hawkins

Two Weeks by Andrea Wolfe