Qatar: Small State, Big Politics

Read Qatar: Small State, Big Politics Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Q

ATAR

Small State, Big Politics

M

EHRAN

K

AMRAVA

C

ORNELL

U

NIVERSITY

P

RESS

I

THACA AND

L

ONDON

To Melisa, Dilara, and Kendra

C

ONTENTS

2. The Subtle Powers of a Small State

3. Foreign Policy and Power Projection

4. The Stability of Royal Autocracy

A

CKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to the many individuals who helped me navigate the science of Qatarology. In particular, Abbas Al-Tonsi, Talal Al-Emadi, Ali Al-Shawi, and Patrick Theros gave generously of their time and shared their insights into Qatari politics and society. Dirk Vandewalle was equally generous with information and sources on the extent and nature of Qatar’s involvement in the Libyan civil war in 2011–2012. At different stages of work on the book, Reem Al Harmi, Dianna Manalastas, Melissa Mannis, and Kasia Rada provided invaluable research assistance, all too often digging up obscure sources and meeting unreasonable deadlines far ahead of schedule and in good cheers. Colleagues at the Center for International and Regional Studies (CIRS) at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service in Qatar, where this book was conceived and completed, helped create a supportive intellectual environment for the book’s writing. A semester’s research leave, kindly provided by Georgetown University, allowed me to concentrate on completing the manuscript. Grateful acknowledgment goes to Carol Lancaster, Marcia Mintz, and James O’Donnell for making the research leave possible, and for their friendship and their professional support over the years. A visiting professorship at the Institut d’Études Politiques at Sciences Po-Lyon provided an idyllic setting for writing the book’s final chapters and for benefiting from the friendship and warm hospitality of Lahouari Addi and Vincent Michelot. Gary Wasserman and Robert Wirsing read all or parts of the manuscript and provided numerous invaluable comments and suggestions. Along with Roger Haydon and anonymous reviewers for Cornell University Press, they helped me refine, sharpen, and better articulate many of the book’s arguments and saved me from a number of embarrassing mistakes. Closer to home, my wife Melisa and our daughters Dilara and Kendra, who have shared with me life in Qatar since 2007, put up with the ups and downs and the exhilarations and frustrations that come with writing a book. For putting up with me during the course of work on this book, and for all they do for me big and small, I dedicate this book to them.

I

NTRODUCTION

The emergence of Qatar as an influential powerbroker in the Middle East and beyond over the past decade has puzzled students and observers of the region alike. How can a small state, with little previous history of diplomatic engagement regionally or globally, have emerged as such an influential and significant player in shaping unfolding events across the Middle East and elsewhere? This is the central question to which this book is devoted. Qatar is a young, small state, with a commensurately small population, sandwiched between giants Iran to the north and Saudi Arabia to the south. But, perhaps audaciously, the sheikhdom, which boasts the world’s highest per capita income, has quickly become one of the most consequential and influential actors in the region. Domestically, Qatar has transformed itself into a global hub and a central pivot of globalization. Doha, the capital, changes by the day, featuring the latest and the best of everything in its streets and its gleaming skyscrapers. The country hosts world-class universities, a world-class museum, and a world-class airline. This much the next-door emirates of Dubai and Abu Dhabi also have. But what sets Qatar apart are its foreign policy and its international relations. The country has pursued a high profile, proactive diplomacy. It has been an active, and mostly successful, mediator, having been instrumental in peace accords in Lebanon in 2008 and in the Sudan in 2011. Qatar played an important role in helping Libyan rebels put an end to Moammar Qaddafi’s rule in 2011, and was similarly instrumental in helping isolate the Assad regime in Syria. Its support and influence is actively courted by powers big and small, near and far. By all accounts, as the events and trends of the past decade are proving, Qatar has undoubtedly emerged as an influential player.

But will it last? Is Qatar’s influence only ephemeral or is it the product of a more lasting and more meaningful shift in power that is likely to mark regional politics in the Middle East for some time to come?

This volume argues that despite all limitations—diplomatic, political, infrastructural, and demographic—Qatar’s powers are more than temporary. Qatar’s influence is likely to continue for some time. In broad strokes, the book’s arguments are as follows. A convergence of two trends, one regional the other global, has created conditions favorable to the rise of Qatar. Regionally, the Middle East has witnessed a precipitous decline in the powers of the some of its traditional heavyweights and a concomitant rise in the affluence and influence of the countries of the Arabian Peninsula. For a number of decades, the Middle East’s centers of diplomatic, military, and ideological power lay in such capitals as Cairo, Damascus, Baghdad, and Tehran. By virtue of being the seat of “the custodian of Islam’s holiest mosques,” Riyadh was also a contender for regional power and supremacy. However, by the 1980s and 1990s, political rhetoric and appearances could no longer mask profound institutional and infrastructural weaknesses characterizing the Egyptian, Syrian, Iraqi, and Iranian polities. Youth bulges and burgeoning populations, economic underperformance and chronic inefficiency, broken infrastructures and reactive policies, all had the traditional powers of the Middle East fighting rearguard action, and, in the process, losing one political, economic, ideological, and diplomatic battle after another. This decline has continued into the 2000s and 2010s, its consequences made all the more dramatic by the outbreak of the Arab Spring of 2011.

At the very time as this steady decline has been occurring in parts of the Middle East, elsewhere in the region, along the southern shores of the Persian Gulf, a group of dynamic, innovative upstarts have been busily filling the ensuing vacuums and making their own presence felt. In sharp contrast to the sluggish, even stalled and broken politics and economics of their fellow Middle Easterners, the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) have proven themselves to be adept at change, proactive, dynamic, and focused. That they are only a mere decades old, and that most would not have existed today had it not been for oil, only adds to their dynamism and their determination to succeed. Within the GCC, Qatar stands out, benefiting from a number of comparative advantages that the other states do not have, having transformed itself from a poor backwater and a practical vassal of Saudi Arabia a few decades ago into one of the region’s richest, most recognizable, and highly influential states.

This steady shift has occurred within the context of a second, global trend, namely a qualitative change in the nature of international power. Power has traditionally been assumed to come from the barrel of a gun, or a tank, or, more recently, from the force of ideals and values. Both hard and soft powers do and will continue to remain highly consequential for the foreseeable future. But we cannot ignore the significance of a new form of power and influence, one less obvious and more discreet, rooted in a combination of contextual opportunities and calculated policies meant to augment one’s influence over others. This “subtle power” is what Qatar has and what is likely to sustain its influence for some time to come.

States may appear powerful and influential internationally but be rotten—or at least weak—at their core. What is the Qatari state’s core like, and what are the sources of its resilience or weakness? Can the archaic-looking system of personal rule, that relic of a bygone era in the post–Arab Spring Middle East, continue to survive and to thrive into the twenty-first century? Does power, even in its subtle variety, not require strength and stability within?

Here the argument becomes somewhat problematic since agency, that unpredictable variable of human actions and initiatives, becomes a far more consequential factor than the role of circumstances and institutions. There can be no doubt that in Qatar and elsewhere in the Arabian Peninsula monarchy as an institution—as an integral part of the social fabric—will continue to be on solid grounds for decades to come. Since the mid-1990s, one of the biggest distinguishing factors about the Qatari monarchy has been the acumen, determination, and savvy of the current monarch, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani. Driven and ambitious, Hamad has been a master-balancer, successfully striking multiple balances between domestic, regional, and international actors while steadily enhancing his own, and his country’s, position. Whether the next monarch can have the same drive and determination, the same uncanny ability to position himself at the apex of an uncontested domestic power structure and the country as a regional leader and a global player is an open question. The heir apparent, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, has so far remained largely in the shadow of his father. All indications are that the emir and the heir apparent see eye-to-eye on matters of policy and direction. But the son remains as yet untested. Nevertheless, in chapters 4 through 6 I make the case that Hamad has positioned both the institution of the monarchy and Qatar’s international profile in such ways that even a less capable or ambitious heir cannot significantly lessen the country’s international influence or slow the pace of its upward ascent.

A Snapshot of Qatar

At first glance, it is easy to dismiss Qatar and most of the other countries of the Arabian Peninsula. Many in the Arab world sarcastically dismiss the small states of the Arabian Peninsula as “oil well states” (

al-dawla al-bi’r

), pointing to their need to incorporate the word “state” into their formal name as an indication of their self-doubt as viable states.

1

Even scholars have long neglected Qatar, with only a few articles and an odd book here or there published on the country well into the 1990s.

2

Even today, despite the belated realization of the country’s growing international significance, there are still no more than a handful of serious treatments on Qatar’s domestic and international politics.

3

Of late a promising cadre of younger scholars have pointed to the growing strategic and commercial significance of the Persian Gulf. Still, Qatar itself remains largely below the scholarly radar, frequently overlooked by observers of the region in favor of its larger or more troubled neighbors—the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, or Bahrain.

Well into the twenty-first century, like the rest of the states of the GCC, Qatar continues to “struggle for self-definition and redefinition.”

4

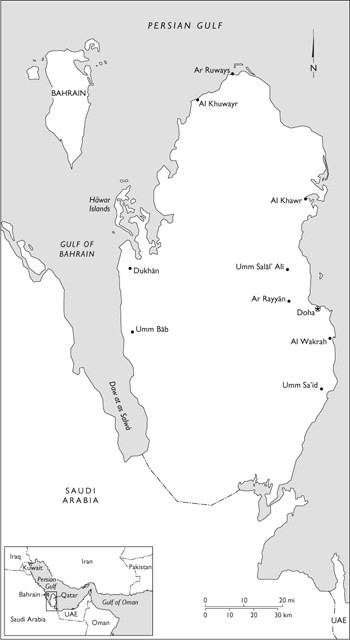

Part of the problem with visibility and recognition has been the country’s small geographic and demographic size. With a landmass of only 4,416 square miles, Qatar is one of the smallest countries in the Middle East, second only to Bahrain with 274 square miles. The country also has the second smallest population base in the Middle East. According to the latest national census, in 2010 Qatar had a total population of 1.74 million.

5

Although the census does not distinguish between nationals and nonnationals, expatriates are estimated to make-up approximately 85 percent of all individuals living in the country. That means Qatari nationals number somewhere in the neighborhood of 250,000. Of these, some 10,000 to 15,000 are thought to be members of the extended ruling Al Thani family.

Despite claims by members of the ruling family that the country’s origins date back to the Phoenicians, there is little archeological evidence to suggest that Doha was much more than a dusty and largely inhospitable fishing village well into the 1920s and 1930s. Chapter 4 discusses the state’s efforts and inventing and reinventing Qatari tradition and heritage, and today’s Doha, where three-quarters of the country’s population lives, seems obsessed with its image as a modern city that remains mindful of its past. Writing on Dubai, Jeremy Jones has used the designation “the airport state” to describe a city that has all the accruements and the modern façade and conveniences of an airport, but is, also like airports the world over, characterless and without a soul of its own.

6

He might as well have been describing Doha. Though considerably less hyper—and hyped—than Dubai, Doha is also a city with little character or charm of its own. The city has a fascination with making and remaking itself, resulting in what is an incongruent collection of impressive but nonharmonious buildings and neighborhoods. Romanticized replicas of Venice form luxury areas and landmarks of the city, bearing names such as Aspire (sports complex), the Pearl (artificial island), and Villaggio (shopping mall).

Time

magazine called the country “the magic kingdom.”

7

Some old forts, a few on the outskirts of the city, are being restored in an effort to buttress the state’s invention—or reinvention—of a Qatari tradition. The heritage industry is doing brisk business in Qatar, seeking to reinvent tradition, so far with uneven success.

Doha may lack Dubai’s obsession with bling, but it is still filled with a glitz that numbs the senses and distorts perceptions of reality. Many parts of the city resemble a surreal and incongruent mixture of Hong Kong, on the one hand, and Tucson, Arizona, on the other. It is not surprising that today’s Doha is one massive construction site. No sooner are city maps printed that they become obsolete, as new roads and multilane highways replace old, snaky streets. Roundabouts, marvels of traffic engineering from a bygone era of few cars and manageable street flows, are being steadily replaced with four-corner junctions with timed traffic lights. Cranes and other heavy construction equipment are ubiquitous features of the urban landscape. Doha, it seems, is addicted to tearing up its asphalted streets as soon as they are ready for use. Entire neighborhoods made-up of older shops and large, single-family homes are razed with unsettling frequency and replaced by tall, glass-covered, gleaming buildings. Remembering directions to points of interest is often an exercise in futility. Taxi passengers frequently find themselves giving directions to their drivers, most of whom are recent arrivees from Bangladesh or Ethiopia.

Doha’s roads and streets, meanwhile, are seldom without mangled cars strewn on the sides, a product of one of the world’s highest and deadliest traffic accident rates.

8

The municipality’s installation of speed cameras all across the city has done little to encourage a culture of diving safely.

9

Unsurprisingly, most Qataris prefer larger, presumably safer cars. The ubiquitous Toyota Land Cruiser, overwhelmingly in white, is the king of Doha roads, the preferred car of Qataris, and a significant status symbol. In recent years, more daring colors of black and gray can also be seen darting around town.

All the while, the city’s armies of construction workers, in their tens of thousands, remain as inconspicuous and hidden from public view as possible. The state employs a discourse revolving around the protection of the family to bar “bachelors” from shopping malls and the

souq

on “family days” and from living in “family residential areas.”

10

In this sense “bachelor” is code word for unskilled migrant workers from South Asia and “family” designates everyone else, married or not. The biggest interaction between unskilled migrant workers and the rest of the country’s residents, save for household maids, occurs on Doha’s congested streets, where, stuck in traffic, tired eyes peer through half-open windows of old American school buses or grungy ones made by Tata as the workers are driven from future high-rises to their distant labor camps.

11

Why Qatar?

The study of Qatar is important in four significant respects. First, Qatar allows us to re-examine some of the basic premises of “rentier” theory, looking, specifically, at the mutually dependent nature of the relationships that develop between the state (i.e., the ruling family) and influential social actors as a result of rent-based political and economic arrangements. The nature of state capacity in Qatar has enabled the ruling family to abandon its repeated mentions of political liberalization and to instead push forward with ambitious agendas of economic and social change. Significantly, an expansion in the state’s capacity has occurred at the same time as its deepening financial and institutional ties with social actors, thereby involving private capital more intimately in the country’s march toward economic growth and modernization. The genesis of such ties trace back to rent-based clientelism, but today these ties have become so robust and multidimensional that even economic downturns are unlikely to turn social actors against the state and its expansive patronage network.