Qatar: Small State, Big Politics (11 page)

Read Qatar: Small State, Big Politics Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

A second element of subtle power is the prestige that derives from brand recognition and developing a positive reputation. Countries acquire a certain image as a result of the behaviors of their leaders domestically and on the world stage, the reliability of the products they manufacture, their foreign policies, their responses to natural disasters or political crises, the scientific and cultural products they export, and the deliberate marketing and branding efforts they undertake. These may be derived from such diverse sources as a political leader’s speeches to home crowds or at the United Nations, the consumer products that are affiliated with a country (especially automobiles and household appliances), movies or other artistic products that are exported abroad, or commonplace portrayals of a country and its leaders in the international media. When the overall image that a country thus acquires is on the whole positive—when, in Nye’s formulation, it has soft power—then it can better position itself to capitalize on international developments to its advantage. By the same token, soft power enables a country to ameliorate some of the negative consequences of its missteps and policy failures.

95

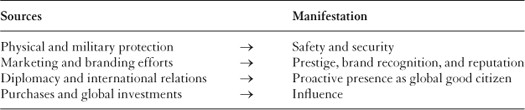

TABLE 2.1.

Key elements of subtle power

Sometimes a positive image builds up over time. Global perception of South Korea and its products is a case in point. Despite initial reservations by consumers when they first broke into American and European markets in the 1980s, today Korean manufactured goods enjoy generally positive reputations in the United States and Europe.

96

At other times, as in the cases of Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Qatar, political leaders try to build up an image and develop a positive reputation overnight. They hire public relations firms, take out glitzy advertisements in billboards and glossy magazines around the world, buy world-famous sports teams and stadiums, and sponsor major sporting events that draw world-renowned athletes and audiences from across the world. They spare no expenses in putting together national airlines that consistently rank at or near the top, spend millions of dollars on international conferences that draw to their shores world leaders and global opinion-makers, and build entire cities and showcase buildings that are meant to rival the world’s most magnificent landmarks.

By themselves, prestige and reputation are of little utility in international affairs. But properly crafted and employed, they can help a country carve out strategic niches for itself in targeted areas. Prestige can enhance overall effectiveness in agenda-setting and in influencing frameworks and preferences. Through focused expenditures on and apparent specializations in specific fields—such as sports, aviation, heritage conservation, interfaith dialogue, or international conflict resolution—a country can acquire expertise and aspire to norm entrepreneurship in that particular field. In international forums and even within regional and international organizations, such as the Gulf Cooperation Council or the European Union, it can develop a positive reputation and even influence in that field.

This positive reputation is in turn reinforced by a third element of subtle power, that is proactive presence on the global stage. International branding and marketing efforts may be done by state-owned or even private enterprises with indirect support by the state. But they are complemented by a deliberately crafted diplomatic posture aimed at projecting an image of the country as a global good citizen. This is also part of a branding effort, but it takes the form of diplomacy rather than deliberate marketing and global media advertising. In Qatar’s case, this diplomatic hyperactivism is part of a hedging strategy, as compared to bandwagoning or balancing, that has enabled the country to maintain open lines of communication, if not altogether friendly relations, with multiple international actors that are often antagonistic to one another (such as Iran and the United States). What on the surface may appear as paradoxical, perhaps even mercurial, foreign policy pursuits, is actually part of a broader, carefully nuanced strategy to maintain as many friendly relationships around the world as possible.

Qatar has sought to carve out a diplomatic niche for itself in a field meant to enhance its reputation as a global good citizen, namely mediation and conflict resolution.

97

In a region known for its intra- and international crises and conflicts, Qatar has, so far largely successfully, projected an image for itself as an active mediator, a mature voice of reason calming tensions and fostering peace. The same imperative of appearing as a global good citizen were at work in Qatar’s landmark decision to join NATO’s military campaign in Libya against Colonel Qaddafi in March 2011. Speculation abounds as to the exact reasons that prompted Qatar to join that campaign.

98

Clearly, as with its mediation efforts, Qatar’s actions in Libya were motivated by a hefty dose of realist considerations and calculations of possible benefits and power maximization.

99

But the value of perpetuating a positive image through “doing the right thing,” at a time when the collapse of the Qaddafi regime seemed only a matter of time, appears to trump other considerations. The remarks of a well-placed official and a member of the ruling family are telling. “We believe in democracy,” he said, referring to Qatar’s involvement in Libya. “We believe in freedom, we believe in dialogue, and we believe in that for the entire region…I am sure the people of the Middle East and other countries will see us as a model, and they can follow us if they think it is useful.”

100

The final and perhaps most important element of subtle power is wealth, a classic hard power asset. Money provides influence within and control and ownership over valuable economic assets spread around the world. This ingredient of subtle power is the influence and control that is accrued through persistent and often sizeable international investments. As such, this aspect of subtle power is a much more refined and less crude version of “dollar diplomacy,” through which the regional rich seek to buy off the loyalty and fealty of the less well-endowed. Although by and large commercially driven, these investments are valued more for their long-term strategic dividends than for their short-term yields. So as not to arouse suspicion or backlash, these investments are seldom aggressive. At times, they are often framed in the form of rescue packages that are offered to long-standing international companies with well-known brand names facing financial distress. Carried through the state’s primary investment arm the sovereign wealth fund (SWF), international investments were initially meant to diversify revenue sources and minimize risk from heavy reliance on energy prices. The purported wealth and secrecy of SWFs has turned them into a source of alarm and mystique for Western politicians and has ignited the imagination of bankers and academics alike.

101

By itself, a SWF or other forms of international investment do not yield influence and power.

102

But wealth does give the state controlling the SWF the confidence it would not otherwise have had in its domestic and foreign policy pursuits. In international politics, wealth by itself does not garner power and influence. But it does foster and deepen self-confidence among the political leaders of wealthy countries. Wealth enables state leaders to aggressively brand their country, if they choose to do so. It also gives them the confidence and the resources to be diplomatically proactive and to engage in hedging. Wealth facilitates access, provides opportunities and space for being heard, and enables leaders to be better positioned to devise a “grand strategy” for their country. In Nye’s words,

A state’s “grand strategy” is its leaders’ theory and story about how to provide for its security, welfare, and identity,…and that strategy has to be adjusted for changes in context. Too rigid an approach to strategy can be counterproductive. Strategy is not some symmetrical possession at the top of the government. It can be applied at all levels. A country must have a general game plan, but it must also remain flexible in the face of events.

103

Clearly, agency is an important component of subtle power. More specifically, subtle power emerges not so much as a result of a confluence of institutional and structural forces, but is instead a product of deliberate decisions and carefully calculated choices made by policymakers. There are a number of wealthy countries in the Persian Gulf and elsewhere, some of which even employ proactive diplomacy as a favored foreign policy option. In Southeast Asia, for example, Malaysia and Singapore’s foreign policies in response to a rising China give meaning to the very essence of hedging.

104

Others with similar predicaments may also be engaged in aggressive branding and marketing campaigns. The emirates of Abu Dhabi and Dubai, for example, often compete with one another and with Qatar in their global branding efforts.

105

But subtle power requires coordinating synergies between all four of its ingredients—military protection and security, global branding, hedging and proactive diplomacy, and international investments—and such a coordination does not occur on its own. It requires purposive choices and carefully calibrated policies. Uniquely, the Qatari leadership has been able to combine all four elements, resulting in a foreign policy that on the surface may appear “maverick” or “paradoxical,” and the cause of much speculation, and fulltime employment, for Western journalists and diplomats.

106

In reality, it is a foreign policy aimed at deepening, and at the same time regenerating, the country’s subtle power.

Qatar and the Pursuit of Subtle Power

Realists famously see the international arena as one existing in a state of anarchy, which fosters self-help on the part of individual states, whereby states cannot help but to look after their own interests. Doing so requires relying “on the means they can generate and the arrangements they can make for themselves.”

107

It appears that this is precisely what Qatar is doing. Despite structural constraints imposed by its small size and its unenviable geographic location, sandwiched as it is between Saudi Arabia to the south and Iran to the north, the dependent variables outlined here—hedging, branding, state autonomy, and comparative economic advantage—have combined to propel Qatar into a position of prominence and influence. Undoubtedly, size does matter.

108

But it necessarily need not be a constraint. In fact, as we have seen Qatar has gone beyond ensuring its survivability and resilience and has managed to emerge as a regional powerhouse of sorts commercially and diplomatically.

Qatar’s emergence as a significant player in regional and international politics is facilitated through a combination of several factors, chief among which are a very cohesive and focused vision of the country’s foreign policy objectives and its desired international position and profile among the ruling elite, equally streamlined and agile decision-making processes, immense financial resources at the hands of the state, and the state’s autonomy in the international arena to pursue foreign policy objectives. Reinforcing all this has been a tremendous amount of self-confidence on the part of the state elites in foreign policymaking. This self-confidence has resulted in the country beginning to play a regional role far beyond its size and youth would otherwise accord it. Qatar may be a young and small state, but the chief architects of its foreign policy, namely the emir and the prime minister, and, increasingly, the Heir Apparent Sheikh Tamim, perceive their country as a regional agenda-setter and a central player in regional politics and diplomacy.

Before delving into the details of how Qatar goes about constructing its new regional and international profile, it is important to see what, if any, generalizable conclusions can be drawn based on the Qatari example concerning the study of power and also small states. Insofar as power is concerned, the Qatari case demonstrates that traditional conceptions of power, while far from having become altogether obsolete, need to be complemented with considerations arising from new and evolving global realities. For a few years now, observers have been speculating about the steady shift of power and influence away from the West—its traditional home for the past five hundred years—to the East. In Fareed Zakaria’s words, the “post-American world” may already be upon us.

109

Whatever this emerging world order will look like, it is obvious that the consequential actions of a focused and driven wealthy upstart like Qatar cannot be easily dismissed. Even if the resulting changes are limited merely to the identity of Qatar rather than to what it can actually do, which they are not, they are still consequential far beyond the small sheikhdom’s borders. Change in the identity of actors—in how they perceive themselves and are perceived by others—can lead to changes in the international system.

110

Qatar may not yet have redrawn the geostrategic map of the Middle East, and whether that is indeed what it seeks to do is open to question. But its emergence as a critical player in regional and global politics, and its seeming continued ascent, are theoretically as important as they are empirically observable.