Quirkology (10 page)

Authors: Richard Wiseman

Over the course of several studies, Kraut and his colleagues secretly observed more than 2,000 bowls. Each time, the researchers carefully documented the course of events, including the bowlers’ facial expressions, their scores, and whether they were facing the bowling lane or their friends. In one part of the study, the team quietly muttered the information into a dictaphone (avoiding possible suspicion by using code words for each factor) to ensure that their measurements were accurately recorded. Their findings revealed that only 4 percent of bowlers smiled when they obtained a good score, but they were facing away from their colleagues. However, when the bowlers turned around and looked at their friends, 42 percent of them had a huge smile pasted across their faces. Strong evidence that we don’t smile simply because we are happy, but rather to let others know that we are happy.

Like all social signals, smiling is open to fakery. People often smile to give the impression that they are happy when, deep down, they feel less than joyous. But is a fake smile identical to a genuine smile, or are there telltale facial signals that separate the two expressions? It is an issue that has taxed researchers for more than a hundred years, and one that lay at the heart of an unusual experiment that I recently conducted in an art gallery.

In the previous chapter, I described how the directors of the New Zealand Science Festival were kind enough to let me undertake the second part of the Born Lucky experiment. Before leaving, I suggested to the festival organizers that we stage a second study that would help unmask the secrets of the fake smile. The idea was simple. I wanted people to see several pairs of photographs.

18

Each pair would contain two images of the same person smiling. One of the smiles would be genuine and the other fake, and the public would be asked to spot the genuine grins. A careful comparison of the photographs would reveal whether there were any telltale signs that give away a fake smile, and an analysis of results would determine whether people were able to utilize these signals. After some discussion, we hit upon the idea of staging the study as an exhibition in an art gallery. The Dunedin Public Art Gallery kindly agreed to host the event, ensuring that our unusual art-science exhibition would brush shoulders with works by Turner, Gainsborough, and Monet.

18

Each pair would contain two images of the same person smiling. One of the smiles would be genuine and the other fake, and the public would be asked to spot the genuine grins. A careful comparison of the photographs would reveal whether there were any telltale signs that give away a fake smile, and an analysis of results would determine whether people were able to utilize these signals. After some discussion, we hit upon the idea of staging the study as an exhibition in an art gallery. The Dunedin Public Art Gallery kindly agreed to host the event, ensuring that our unusual art-science exhibition would brush shoulders with works by Turner, Gainsborough, and Monet.

For my smiling experiment, I needed to create a way of having people produce both a genuine and a fake smile. Researchers have used a diverse range of techniques to provoke such facial expressions in the laboratory. In the 1930s, the psychologist Carney Landis wanted to photograph people’s faces as they experienced a range of emotions, and so his researchers asked volunteers to listen to a jazz record, read the Bible, and flick through some pornographic images (Landis reports that “the experimenter was careful not to laugh or appear self-conscious during this last situation”).

19

Two other situations were designed to provoke more extreme reactions. In one, volunteers were asked to place their hands in a pail of water containing three live frogs. After the volunteers had reacted, they were urged to continue feeling around in the water. The experimenter then ran a high voltage through the water, giving the subjects a considerable electric shock. However, Landis’s pièce de résistance involved his final, and ethically most questionable, task. Here participants were handed a live white rat and a butcher’s knife, and asked to behead the rat. Around 70 percent of the volunteers carried out the task after “more or less urging,” and in the remaining cases the experimenter beheaded the rat himself. Landis reports that 52 percent of people smiled during the beheading, compared to 74 percent receiving the electric shock. Most of the volunteers were adults, but the group did include a thirteen-year-old boy who was a patient at the University Hospital because he was emotionally unstable and had high blood pressure (“So, son, what happened at the hospital today?”).

19

Two other situations were designed to provoke more extreme reactions. In one, volunteers were asked to place their hands in a pail of water containing three live frogs. After the volunteers had reacted, they were urged to continue feeling around in the water. The experimenter then ran a high voltage through the water, giving the subjects a considerable electric shock. However, Landis’s pièce de résistance involved his final, and ethically most questionable, task. Here participants were handed a live white rat and a butcher’s knife, and asked to behead the rat. Around 70 percent of the volunteers carried out the task after “more or less urging,” and in the remaining cases the experimenter beheaded the rat himself. Landis reports that 52 percent of people smiled during the beheading, compared to 74 percent receiving the electric shock. Most of the volunteers were adults, but the group did include a thirteen-year-old boy who was a patient at the University Hospital because he was emotionally unstable and had high blood pressure (“So, son, what happened at the hospital today?”).

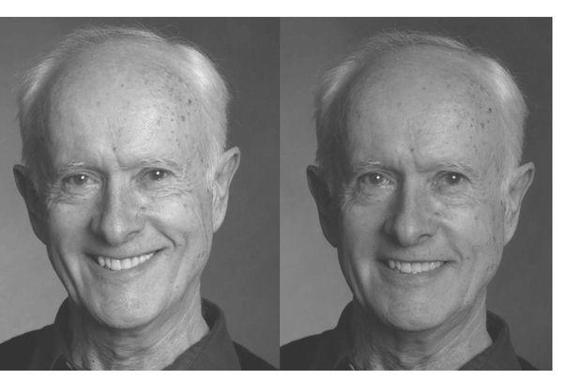

In my smiling study, I asked each of our volunteers to bring along a poodle and a large knife. Just kidding. Actually, we opted for two tasks that were a little less controversial. Each person was asked to come along with a friend. Whenever the friend made the volunteer laugh, we took a photograph of the genuine smile. We then asked volunteers to imagine that they had just met someone they disliked and had to fake a polite smile. Two of the resulting images are shown in

figure 1

. This pair of photographs, and nine other pairs, formed the basis for the exhibition.

figure 1

. This pair of photographs, and nine other pairs, formed the basis for the exhibition.

Fig. 1

Photographs showing either a genuine smile or a fake one.

Photographs showing either a genuine smile or a fake one.

I am not the first academic to examine the science of smiling in an art gallery. In 2003, Margaret Livingstone, a Harvard neuroscientist, attempted to solve scientifically the mystery of perhaps the most famous smile in art.

20

The

Mona Lisa

was created by Leonardo da Vinci in the 1500s, and the painting has perplexed art historians for hundreds of years. Much of the debate has revolved around the nature of the subject’s enigmatic facial expression: Some scholars argue that the painting clearly shows a smiling face, but others claim that the expression is one of great sadness. In 1852, a young French artist threw himself from the fourth-floor window of his Paris hotel after writing these words: “For years I have grappled desperately with her smile. Now I prefer to die.” Livingstone took a somewhat more constructive approach to the issue.

20

The

Mona Lisa

was created by Leonardo da Vinci in the 1500s, and the painting has perplexed art historians for hundreds of years. Much of the debate has revolved around the nature of the subject’s enigmatic facial expression: Some scholars argue that the painting clearly shows a smiling face, but others claim that the expression is one of great sadness. In 1852, a young French artist threw himself from the fourth-floor window of his Paris hotel after writing these words: “For years I have grappled desperately with her smile. Now I prefer to die.” Livingstone took a somewhat more constructive approach to the issue.

People had noticed that Mona Lisa’s smile was far more apparent to viewers when they looked at her eyes, and that it appeared to vanish when they looked directly at her mouth. This was a key part of the enigmatic nature of the painting, but people couldn’t figure out how Leonardo had created the strange effect. Livingstone discovered that the illusion was due to the fact that the human eye sees the world in two very different ways. When you look at something directly, the light falls on a central part of the retina called the fovea. This part of the eye is excellent at seeing relatively bright objects, such as those in direct sunlight. In contrast, when you see something out of the corner of your eye, the light falls on the peripheral part of the retina, which is much better at seeing in semi-darkness. Livingstone found that Leonardo’s picture is using the two parts of the retina to fool the eye. Analyses showed that the artist had cleverly used the shadows from the cheekbones to make the subject’s mouth much darker than the rest of her face. As a result, the subject’s smile appears more obvious when people look at her eyes because they are seeing it in their peripheral vision. When people look directly at her mouth, they are seeing the dark area of the painting more clearly with the fovea, and so the smile looks far less pronounced.

Livingstone was not the first scientist to be intrigued with the mystery of the human smile. Two hundred years earlier, a small band of European scientists conducted a series of strange studies on the same topic.

In the early nineteenth century, researchers were fascinated by how electricity might be used to gain important anatomical and physiological insights. Some of this work involved the rather gruesome, and often public, stimulation of fresh corpses. Perhaps the most famous exponent of this technique was the Italian scientist Giovanni Aldini.

21

Aldini specialized in bringing murderers back to life. In one well-publicized example of his work, Aldini traveled to London to reanimate a murderer named George Foster. Foster had been found guilty of killing his wife and child by drowning them in a canal and had been sentenced to hang on January 18, 1803. Shortly after his death, Foster’s body was taken to a nearby house, where Aldini applied various voltages to his body under the watchful eye of eminent British scientists. The court calendar (subsequently appearing, rather appropriately, in an edited collection of papers by a Mr. G. T. Crook) reported the results:

22

21

Aldini specialized in bringing murderers back to life. In one well-publicized example of his work, Aldini traveled to London to reanimate a murderer named George Foster. Foster had been found guilty of killing his wife and child by drowning them in a canal and had been sentenced to hang on January 18, 1803. Shortly after his death, Foster’s body was taken to a nearby house, where Aldini applied various voltages to his body under the watchful eye of eminent British scientists. The court calendar (subsequently appearing, rather appropriately, in an edited collection of papers by a Mr. G. T. Crook) reported the results:

22

On the first application of the process to the face, the jaws of the deceased criminal began to quiver, and the adjoining muscles were horribly contorted, and one eye was actually opened. In the subsequent part of the process the right hand was raised and clenched, and the legs and thighs were set in motion. It appeared to the uninformed part of the by-standers as if the wretched man was on the eve of being restored to life.

The description then went on to rule out the possibility of resurrection on the grounds that during Foster’s execution “several of his friends who were under the scaffold had violently pulled his legs, in order to put a more speedy termination to his suffering”; it also noted that even if Aldini’s demonstration had brought Foster back to life, he would have been hanged a second time because the law demanded that such criminals be “hanged until they were dead.” The calendar also describes how one of the onlookers, a Mr. Pass, the beadle of the Surgeons’ Company, was so shocked by the demonstration that he died of fright soon after his return home, thus making Foster one of the very few murderers to kill another victim

after

his own death.

after

his own death.

Aldini was not the only scientist to experiment with the effects of electrical stimulation upon the muscles of the body. A few years later, a group of Scottish scientists carried out a similar demonstration with another murderer, contorting the man’s face into “fearful action” and setting his fingers in motion such that “the corpse seemed to point to different spectators.” Again, the resulting scene proved too much for many onlookers, with one man fainting and several leaving the room in disgust.

23

23

In addition to laying the foundations for much modern-day work into the effects of medical electrical stimulation, this research resulted in two significant contributions to popular culture. The use of electricity apparently to resurrect the dead helped inspire Mary Shelley to write

Frankenstein.

Also, the word “corpsing”—a term actors use when they suddenly laugh while trying to be serious—originates in the inappropriate grins exhibited on the lifeless heads.

Frankenstein.

Also, the word “corpsing”—a term actors use when they suddenly laugh while trying to be serious—originates in the inappropriate grins exhibited on the lifeless heads.

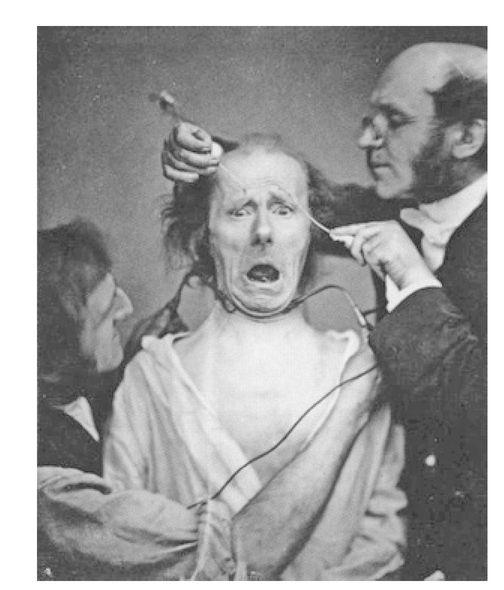

Aldini’s work also inspired a French scientist named Guillaume Duchenne de Boulogne to develop a more sophisticated system for investigating which muscles are involved in different facial expressions. Rather than work with recently executed murderers, Duchenne decided to take the more civilized approach of photographing living subjects as electricity was applied directly to their faces. After much searching, he found a participant who was willing to put up with the constant, and rather painful, stimulation of his face. In his book

The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression,

24

published in 1862, Duchenne presents a less than flattering description of his guinea pig: “The individual I chose as my principal subject for the experiments . . . was an old toothless man, with a thin face, whose features, without being absolutely ugly, approached ordinary triviality, and whose facial expression was in perfect agreement with his inoffensive character and his restricted intelligence.”

The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression,

24

published in 1862, Duchenne presents a less than flattering description of his guinea pig: “The individual I chose as my principal subject for the experiments . . . was an old toothless man, with a thin face, whose features, without being absolutely ugly, approached ordinary triviality, and whose facial expression was in perfect agreement with his inoffensive character and his restricted intelligence.”

In addition, the man had another desirable attribute: almost total facial anesthesia. This meant that Duchenne could “stimulate his individual muscles with as much precision and accuracy as if [he] were working with a still irritable cadaver” (see

fig. 2

).

fig. 2

).

After snapping hundreds of photographs, Duchenne uncovered the secret of the fake smile. When electricity was applied to the cheeks of the face, the large muscles on each side of the mouth—known as the “zygomatic major”—pulled the corners of the lip upward to create a grin. Duchenne then compared this smile with the one produced when he told his thin-faced participant a joke. The genuine smiles included not only the zygomatic major but also the orbicularis oculi muscles that run right around each eye. In a genuine smile, these muscles tighten, pulling the eyebrows down and the cheeks up, producing tiny crinkles around the corners of the eyes. Duchenne discovered that the tightening of the eye muscles lay outside of voluntary control; it was “only put into play by the sweet emotions of the soul.”

Other books

Strange Sweet Song by Rule, Adi

An Awkward Commission by David Donachie

Scandal With a Prince by Nicole Burnham

Saving Phoebe Murrow: A Novel by Herta Feely

Forever (Book #3 in the Fateful Series) by Schmidt, Cheri

The Hunger Trace by Hogan, Edward

Everbound: An Everneath Novel by Ashton, Brodi

Mommy! Mommy! by Taro Gomi

Dreams of a Dark Warrior by Kresley Cole

Harbor Lights by Sherryl Woods