Quirkology (11 page)

Authors: Richard Wiseman

Fig. 2

Duchenne stimulates the face of his volunteer.

Duchenne stimulates the face of his volunteer.

Duchenne’s work has been confirmed by more recent research,

25

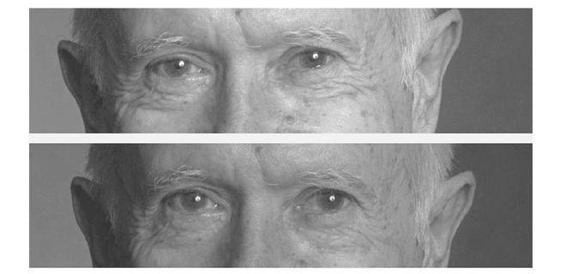

and our twenty-first-century images of genuine and false smiles showed exactly the same effect. Take another look at the two photographs in

figure 1

. The image on the right shows a fake smile in which the zygomatic major muscles are pulling up the corners of the mouth. Researchers have recently christened this the “Pan American” smile, after the fake grin often produced by flight attendants working for the now-defunct airline. The left-hand picture shows a genuine smile in which both the zygomatic major muscles and the orbicularis oculi muscles around the eyes are involved. Here, the upward movement of the cheek has produced more striking contour lines at the sides of the nose and around the bottom and sides of the eyes. Also, the eyebrows, and the skin below the eyebrows, have moved down toward the eyes, making them slightly narrower and creating a “bagging” directly above the eyes. These subtle changes are easier to see in the enlargements of the photographs in

figure 3

(the genuine smile is shown in the top image, and the fake in the bottom).

25

and our twenty-first-century images of genuine and false smiles showed exactly the same effect. Take another look at the two photographs in

figure 1

. The image on the right shows a fake smile in which the zygomatic major muscles are pulling up the corners of the mouth. Researchers have recently christened this the “Pan American” smile, after the fake grin often produced by flight attendants working for the now-defunct airline. The left-hand picture shows a genuine smile in which both the zygomatic major muscles and the orbicularis oculi muscles around the eyes are involved. Here, the upward movement of the cheek has produced more striking contour lines at the sides of the nose and around the bottom and sides of the eyes. Also, the eyebrows, and the skin below the eyebrows, have moved down toward the eyes, making them slightly narrower and creating a “bagging” directly above the eyes. These subtle changes are easier to see in the enlargements of the photographs in

figure 3

(the genuine smile is shown in the top image, and the fake in the bottom).

Fig. 3

Close-up of the genuine and fake smiles.

Close-up of the genuine and fake smiles.

Hundreds of people visited the Dunedin Public Art Gallery during the festival and were happy to take part in the experiment. Participants were given a questionnaire, asked to look at each pair of photographs, and instructed to indicate which of them they believed showed the genuine smile. The results revealed that many people couldn’t tell the fake from the genuine smiles, and even those who thought they were especially sensitive to the emotions of others scored little better than chance. Had they known exactly what to look for, however, the telltale clue was right in front of their noses (and just to the sides of the noses of the people in the photographs).

The people participating in the study were not especially skilled at spotting a genuine smile. The ability to differentiate between the two, however, using the type of system developed by Duchenne, has provided psychologists with a unique insight into the relationship between emotion and everyday life, to the point that researchers have recently started to look at the way small, and seemingly irrelevant, aspects of a person’s behavior in early life may provide a useful insight into his or her long-term success and happiness.

The idea is beautifully illustrated by a study involving two hundred nuns carried out by Deborah Danner, a psychologist at the University of Kentucky.

26

Before joining an American nunnery known as the School Sisters of Notre Dame, each nun is required to write an autobiographical account of her life. In the early 1990s, Danner analyzed 180 autobiographies written by nuns who had joined the order in the mid-1970s, counting the frequency with which words describing positive emotions, such as “joy,” “love,” and “content,” appeared. Remarkably, nuns who described experiencing a large number of positive emotions lived as much as ten years longer than the others.

26

Before joining an American nunnery known as the School Sisters of Notre Dame, each nun is required to write an autobiographical account of her life. In the early 1990s, Danner analyzed 180 autobiographies written by nuns who had joined the order in the mid-1970s, counting the frequency with which words describing positive emotions, such as “joy,” “love,” and “content,” appeared. Remarkably, nuns who described experiencing a large number of positive emotions lived as much as ten years longer than the others.

Similar work suggests that the presence of the Duchenne smile in early adulthood provides a deep insight into people’s lives. In the late 1950s, about 150 senior students at Mills College (a private women’s college in Oakland, California) agreed to allow scientists to conduct a long-term study of their lives. During the next fifty years, these women provided researchers with ongoing reports about their health, marriages, family lives, careers, and happiness. A few years ago, Dacher Keltner and LeeAnne Harker, from the University of California at Berkeley, looked at the photographs of the women that had been taken for the college yearbook when they were in their early twenties.

27

Nearly all the women were smiling. However, when the researchers carefully examined the images, they noticed that about half of the photographs showed a Pan Am smile and half a genuine Duchenne smile. They then went back to the information that had been provided by the women throughout their lives, and they discovered something remarkable. Compared to the women with the Pan Am smiles, those displaying the Duchenne smiles were significantly more likely to be married, to stay married, to be happier, and to enjoy better health throughout their lives.

27

Nearly all the women were smiling. However, when the researchers carefully examined the images, they noticed that about half of the photographs showed a Pan Am smile and half a genuine Duchenne smile. They then went back to the information that had been provided by the women throughout their lives, and they discovered something remarkable. Compared to the women with the Pan Am smiles, those displaying the Duchenne smiles were significantly more likely to be married, to stay married, to be happier, and to enjoy better health throughout their lives.

Lifelong success and happiness can be predicted by the simple crinkling around the sides of the eyes that first caught Duchenne’s attention more than a century ago. Interestingly, Duchenne realized the importance of his discovery long before his fellow scientists. Summing up his feelings about his research at the end of his career, Duchenne noted: “You cannot exaggerate the significance of the fake smile. The expression which can be both a simple smile of politeness, or act as a cover to treason. The smile that plays upon just the lips when our soul is sad.”

When it comes to everyday deception, the language of lying and fake smiles is just the beginning of the story.

In the mid-1970s, psychologists started to take a serious look at the malleability of memory. In a classic series of experiments conducted by Elizabeth Loftus and her colleagues, participants were shown slides depicting a car accident.

28

Everyone saw a red Datsun driving along a road, turning at a junction, and then hitting a pedestrian. After seeing the slides, participants were fed misleading information in a very sneaky way. In reality, the slide of the road junction had contained a stop sign. However, the experimenters wanted to deceive participants subtly by suggesting that they had seen a different sign, and so asked them to name the color of the car that drove through the yield sign. Later on, the participants were shown a slide of the junction showing either a stop sign or a yield sign and asked to say which they had seen before. The majority were sure they had originally seen a yield sign at the junction. The study led to a whole raft of similar experiments in which people were persuaded to recall hammers as screwdrivers,

Vogue

magazine as

Mademoiselle

magazine, a clean-shaven man as having a moustache, and Mickey Mouse as Minnie Mouse.

28

Everyone saw a red Datsun driving along a road, turning at a junction, and then hitting a pedestrian. After seeing the slides, participants were fed misleading information in a very sneaky way. In reality, the slide of the road junction had contained a stop sign. However, the experimenters wanted to deceive participants subtly by suggesting that they had seen a different sign, and so asked them to name the color of the car that drove through the yield sign. Later on, the participants were shown a slide of the junction showing either a stop sign or a yield sign and asked to say which they had seen before. The majority were sure they had originally seen a yield sign at the junction. The study led to a whole raft of similar experiments in which people were persuaded to recall hammers as screwdrivers,

Vogue

magazine as

Mademoiselle

magazine, a clean-shaven man as having a moustache, and Mickey Mouse as Minnie Mouse.

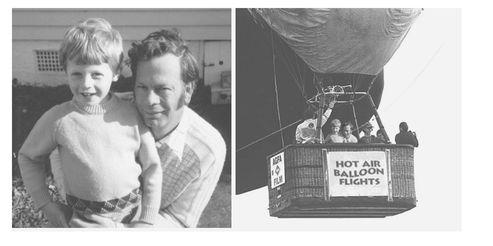

Subsequent research revealed that the same idea can also be used to deceive people into “remembering” events that haven’t actually happened. One recent study, conducted by Kimberley Wade from the Victoria University of Wellington and her colleagues, demonstrated the power of the effect.

29

Wade asked twenty people to persuade a family member to participate in an experiment that was allegedly concerned with why people reminisce about childhood events. The experimenters also asked their recruiters to supply them secretly with a photograph of this person as a young child. The experimenters then used this image to create a fake photograph depicting a childhood trip in a hot-air balloon. One of the original photographs, and the resulting manipulated image, is shown in

figure 4

. Finally, the experimenters asked their recruiters to supply three other photographs showing the person taking part in genuine childhood events, such as a birthday party, a visit to the beach, or day trip to the zoo.

29

Wade asked twenty people to persuade a family member to participate in an experiment that was allegedly concerned with why people reminisce about childhood events. The experimenters also asked their recruiters to supply them secretly with a photograph of this person as a young child. The experimenters then used this image to create a fake photograph depicting a childhood trip in a hot-air balloon. One of the original photographs, and the resulting manipulated image, is shown in

figure 4

. Finally, the experimenters asked their recruiters to supply three other photographs showing the person taking part in genuine childhood events, such as a birthday party, a visit to the beach, or day trip to the zoo.

Fig. 4

Genuine and doctored photographs used in Kimberley Wade’s false-memory experiment.

Genuine and doctored photographs used in Kimberley Wade’s false-memory experiment.

The participants were interviewed three times over the course of two weeks. During each interview, they were shown the three genuine photographs and the fake one and were encouraged to describe as much about each experience as possible. In the first interview, almost everyone was able to remember details of the genuine events, but about a third also said that they remembered the nonexistent balloon trip, which some actually described in considerable detail. The experimenters asked all the participants to go away and think more about the experiences. By the third and final interview, half the participants remembered the fictitious balloon trip, and many described the event in some detail. One participant who, at an initial interview, correctly denied having been in a hot-air balloon, ended up producing the following account of the nonexistent event: “I’m pretty certain it occurred when I was in form one at the local school there . . . basically for $10 or something you could go up in a hot-air balloon and go up about twenty-odd meters . . . it would have been a Saturday and . . . I’m pretty certain that Mum is down on the ground taking a photo.”

Wade’s work is just one of a long line of experiments showing that people can be manipulated into recalling events that simply didn’t happen. In another set of studies, participants were persuaded to provide detailed accounts of how, as children, they visited Disneyland and met someone dressed in a Bugs Bunny costume (Bugs is not a Disney character, and so would not have been in Disneyland).

30

The well-known “shopping mall” study had experimenters interview the parents of potential participants and ask them whether their offspring had ever become lost in a shopping mall as children.

31

After carefully selecting a group of people who had not experienced this event, the experimenters managed to persuade a large percentage of them to provide a detailed account of this traumatic, but nonexistent, experience. Related research has convinced people that they once experienced an overnight hospitalization for a high fever with a possible ear infection, accidentally spilled a punch bowl over the parents of the bride at a wedding reception, had to evacuate a grocery store because the sprinkler system was set off, and caused a car to roll into another vehicle by releasing its brake.

32

30

The well-known “shopping mall” study had experimenters interview the parents of potential participants and ask them whether their offspring had ever become lost in a shopping mall as children.

31

After carefully selecting a group of people who had not experienced this event, the experimenters managed to persuade a large percentage of them to provide a detailed account of this traumatic, but nonexistent, experience. Related research has convinced people that they once experienced an overnight hospitalization for a high fever with a possible ear infection, accidentally spilled a punch bowl over the parents of the bride at a wedding reception, had to evacuate a grocery store because the sprinkler system was set off, and caused a car to roll into another vehicle by releasing its brake.

32

The work shows that our memories are far more malleable than we would like to believe. Once an authority figure suggests that we have experienced an event, most of us find it difficult to deny it and we start to fill in the gaps from imagination. After a while, it becomes almost impossible to separate fact from fiction, and we start to believe the lie. The effect is so powerful that sometimes it doesn’t even require the voice of authority to fool us. Sometimes we are perfectly capable of fooling ourselves.

In December 1983, President Ronald Reagan addressed the Congressional Medal of Honor Society. He decided to relate an alleged real-life story that he had told many times before. Reagan described how, during World War II, a B-17 bomber badly damaged by antiaircraft fire was limping its way home across the English Channel. The gun turret that hung beneath the plane had been hit; the gunner inside was injured and the door of the turret had jammed shut. When the plane started to lose altitude, the commander ordered his men to bail out. The gunner was trapped in the turret and knew he was going to go down with the plane. The last man to jump out of the plane later described how he saw his commander sitting next to the turret and telling the terrified gunner: “Never mind, son, we’ll ride it down together.”

Reagan explained how this remarkable act of courage had resulted in the commander’s being posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, and ended this part of his emotional speech by noting how the United States had been right to award its highest honor “to a man who would sacrifice his life simply to bring comfort to a boy who had to die.” It is a wonderful story, and it suffers from only one small problem: It never happened. After checking the citations of all 434 Congressional Medals of Honor awarded during World War II, journalists could find no mention of the episode or anything like it. Eventually, a member of the public pointed out that the story was a near-perfect fit to events portrayed in the popular wartime film

A Wing and a Prayer.

In the climactic scene of the film, a radio operator informs the pilot that the plane is badly damaged, and that he is injured and cannot move. The pilot replies, “I haven’t got the altitude, Mike. We’ll take this ride together.”

A Wing and a Prayer.

In the climactic scene of the film, a radio operator informs the pilot that the plane is badly damaged, and that he is injured and cannot move. The pilot replies, “I haven’t got the altitude, Mike. We’ll take this ride together.”

Other books

The Dragon Lantern by Alan Gratz

Earth and High Heaven by Gwethalyn Graham

Every Day After by Laura Golden

Caged Eagles by Eric Walters

The Murder at Sissingham Hall by Clara Benson

Quiet Nights by Mary Calmes

The Thomas Berryman Number by James Patterson

Song of Susannah by Stephen King

Long Summer Nights by Kathleen O'Reilly

Kristin Lavransdatter by Undset, Sigrid