Quirkology (27 page)

Authors: Richard Wiseman

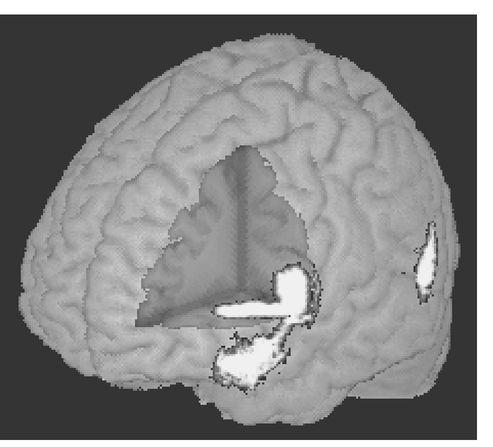

Fig. 9

A 3D scan showing the parts of the brain involved in finding jokes funny.

A 3D scan showing the parts of the brain involved in finding jokes funny.

This work supported other research showing that people who have experienced damage to the right hemisphere are less able to understand jokes, and so they don’t see the funny side of life.

15

Take a look at the following setup line and then the three possible punch lines, and see whether you can choose the correct one:

15

Take a look at the following setup line and then the three possible punch lines, and see whether you can choose the correct one:

A man went up to a lady in a crowded square. “Excuse me,” he said, “Do you happen to have seen a policeman anywhere around here?”“I’m sorry,” the woman answered, “but I haven’t seen one for ages.”

Potential punch lines:

A “Oh, OK, can you give me your watch and necklace then.”B “Oh, OK, it’s just that I’ve been looking for one for half an hour.”C “Baseball is my favorite sport.”

The first punch line is obviously correct. The second one makes sense, but isn’t funny. And the third does not make sense,

and

isn’t funny. People with damage to the right side of the brain tended to choose the third punch line far more often than people who did not have any brain damage. It seems that these people know that the end of the joke should be surprising, but they have no way of knowing that one of the punch lines could be reinterpreted to make sense. Interestingly, these people still find films of slapstick comedians funny—although they haven’t lost their sense of humor, they have lost the ability to work out why certain incongruities are funny and others aren’t. Some of the researchers conducting this work summed up the situation this way: “While the left hemisphere might appreciate some of Groucho’s puns, and the right hemisphere might be entertained by the antics of Harpo, only the two hemispheres united can appreciate a whole Marx Brothers routine.” As the journalist Tad Friend dryly noted in his

New Yorker

article on LaughLab, neither hemisphere seems to find Chico funny.

16

and

isn’t funny. People with damage to the right side of the brain tended to choose the third punch line far more often than people who did not have any brain damage. It seems that these people know that the end of the joke should be surprising, but they have no way of knowing that one of the punch lines could be reinterpreted to make sense. Interestingly, these people still find films of slapstick comedians funny—although they haven’t lost their sense of humor, they have lost the ability to work out why certain incongruities are funny and others aren’t. Some of the researchers conducting this work summed up the situation this way: “While the left hemisphere might appreciate some of Groucho’s puns, and the right hemisphere might be entertained by the antics of Harpo, only the two hemispheres united can appreciate a whole Marx Brothers routine.” As the journalist Tad Friend dryly noted in his

New Yorker

article on LaughLab, neither hemisphere seems to find Chico funny.

16

K

In January 2002, Emma Greening walked into my office and said, “I just don’t get it, we are receiving a joke every minute, and they all end with the same punch line: ‘There’s a weasel chomping on my privates.’” We were five months into the project and, unbeknown to us, Dave Barry had just devoted an entire column to our work in the

International Herald Tribune.

17

In a previous column, Barry claimed that any sentence can be made much funnier by the insertion of the word “weasel.”

18

In his column about LaughLab, Barry repeated his theory and urged his readers to submit jokes to our experiment that ended with the punch line “There’s a weasel chomping on my privates.” In addition, he asked people to assign any weasel joke a maximum 5 points whenever it was chosen from the archive. Within just a few days, we had received more than 1,500 “weasel chomping” jokes.

International Herald Tribune.

17

In a previous column, Barry claimed that any sentence can be made much funnier by the insertion of the word “weasel.”

18

In his column about LaughLab, Barry repeated his theory and urged his readers to submit jokes to our experiment that ended with the punch line “There’s a weasel chomping on my privates.” In addition, he asked people to assign any weasel joke a maximum 5 points whenever it was chosen from the archive. Within just a few days, we had received more than 1,500 “weasel chomping” jokes.

Barry is not the only humorist to develop a theory about which words, and sounds, make people laugh. The results from one of the mini-experiments that we conducted during LaughLab supported the most widely cited of these theories: the mysterious comedy potential of the letter

k.

k.

Early in the experiment, we received the following submission:

There were two cows in a field. One said: “Moo.” The other one said: “I was going to say that!”

We decided to use the joke as a basis for a little experiment. We reentered the joke into our archive several times, using a different animal and noise. We had two tigers going “Gruurrr,” two birds going “Cheep,” two mice going “Eeek,” two dogs going “Woof,” and so on. At the end of the study, we examined what effect the different animals had had on how funny people found the joke. In third place came the original cow joke, second were two cats going “Meow,” but the winning animal noise joke was:

Two ducks were sitting in a pond. One of the ducks said: “Quack.” The other duck said: “I was going to say that!”

Interestingly, the

k

sound (as in the “hard

c

”) is associated with both “quack” and “duck” and has long been seen by comedians and comedy writers as being especially funny. The idea of the comedy

k

has certainly made it into popular culture. In the

Star Trek: The Next Generation

episode “The Outrageous Okona,” a comedian refers to the idea when attempting to explain humor to the android Data. There was also an episode of

The Simpsons

in which Krusty the Clown (note the

k

’s) visits a faith healer because he has paralyzed his vocal chords trying to cram too many “comedy

k

’s” into his routines. After being healed, Krusty exclaims that he is overjoyed to get his comedy

k

’s back, celebrates by shouting out “King Kong,” “cold-cock,” and “Kato Kaelin,” and then kisses the faith healer as a sign of gratitude.

k

sound (as in the “hard

c

”) is associated with both “quack” and “duck” and has long been seen by comedians and comedy writers as being especially funny. The idea of the comedy

k

has certainly made it into popular culture. In the

Star Trek: The Next Generation

episode “The Outrageous Okona,” a comedian refers to the idea when attempting to explain humor to the android Data. There was also an episode of

The Simpsons

in which Krusty the Clown (note the

k

’s) visits a faith healer because he has paralyzed his vocal chords trying to cram too many “comedy

k

’s” into his routines. After being healed, Krusty exclaims that he is overjoyed to get his comedy

k

’s back, celebrates by shouting out “King Kong,” “cold-cock,” and “Kato Kaelin,” and then kisses the faith healer as a sign of gratitude.

Why should the

k

sound produce such pleasure? It may be due to an odd psychological phenomenon known as “facial feedback.” People smile when they feel happy. However, evidence suggests that the mechanism also works in reverse; that is, people feel happy simply because they have smiled. In 1988, Fritz Strack and his colleagues from the University of Mannheim, Germany, had people judge how funny they found Gary Larson’s

Far Side

cartoons under one of two conditions.

19

The participants in one group were asked to hold a pencil between their teeth, but to ensure that it did not touch their lips. This forced the lower part of their faces into a smile. Those in the other group were asked to support the end of the pencil with just their lips, and not their teeth. This forced their faces into a frown. The results revealed that people actually experience the emotion associated with their expressions. Those who had their faces forced into a smile felt happier; they found the

Far Side

cartoons much funnier than those who were forced to frown did.

k

sound produce such pleasure? It may be due to an odd psychological phenomenon known as “facial feedback.” People smile when they feel happy. However, evidence suggests that the mechanism also works in reverse; that is, people feel happy simply because they have smiled. In 1988, Fritz Strack and his colleagues from the University of Mannheim, Germany, had people judge how funny they found Gary Larson’s

Far Side

cartoons under one of two conditions.

19

The participants in one group were asked to hold a pencil between their teeth, but to ensure that it did not touch their lips. This forced the lower part of their faces into a smile. Those in the other group were asked to support the end of the pencil with just their lips, and not their teeth. This forced their faces into a frown. The results revealed that people actually experience the emotion associated with their expressions. Those who had their faces forced into a smile felt happier; they found the

Far Side

cartoons much funnier than those who were forced to frown did.

Interestingly, many words featuring the

k

sound force the face into a smile (think “duck” and “quack”), and they may account for why we associate the sound with happiness. Regardless of whether this explains the “comedy

k

” effect, the explanation certainly plays a key role in another aspect of humor—the contagious nature of laughter.

k

sound force the face into a smile (think “duck” and “quack”), and they may account for why we associate the sound with happiness. Regardless of whether this explains the “comedy

k

” effect, the explanation certainly plays a key role in another aspect of humor—the contagious nature of laughter.

In 1991, Verlin Hinsz and Judith Tomhave, psychologists from North Dakota State University, visited various shopping centers to examine smiling.

20

One member of the team smiled at a random selection of people while another experimenter, secreted inside a fake food stand, carefully observed whether the person reciprocated with a smile. After hours of smiling and observing, they discovered that half of people responded to the experimenter’s smile with another smile. Their results caused them to suggest that the old saying “Smile, and the whole world smiles with you” should be altered to the more scientifically accurate “Smile, and

half

the world smiles with you.”

20

One member of the team smiled at a random selection of people while another experimenter, secreted inside a fake food stand, carefully observed whether the person reciprocated with a smile. After hours of smiling and observing, they discovered that half of people responded to the experimenter’s smile with another smile. Their results caused them to suggest that the old saying “Smile, and the whole world smiles with you” should be altered to the more scientifically accurate “Smile, and

half

the world smiles with you.”

The ability automatically, and unconsciously, to mimic the facial expressions of those around us plays a vitally important role in group survival, cohesion, and bonding. By copying the expressions of others, we quickly feel how they feel, and so find it much easier to empathize with their situations and to communicate with them. One person in the group smiles, and others automatically copy the smile and cheer up. Another feels sad or afraid or panicked and, again, the emotion can spread from person to person. This, combined with the results from the pencil experiment, explains why laughter is contagious. When people see or hear another person laugh, they are far more likely to copy the behavior, start laughing themselves, and therefore actually find the situation funny. This is the reason why so many television comedy programs carry laughter tracks, and why nineteenth-century theater producers would hire a “professional” audience member (known as the

rieur

) whose especially infectious laugh encouraged the entire audience to giggle and guffaw.

rieur

) whose especially infectious laugh encouraged the entire audience to giggle and guffaw.

Although this contagion usually has limited effects, sometimes it can get out of hand, and an otherwise inexplicable epidemic of laughter can sweep through thousands of people. In January 1962, three teenaged girls attending a missionary-run boarding school in Tanzania started laughing.

21

Their hilarity quickly spread to 95 of the 159 pupils at the school, and by March the school was forced to close. It is reported that the attacks of laughing lasted from minutes to hours, and although debilitating, did not result in any fatalities. The school reopened in May but was again forced to close within weeks when another 60 pupils were struck down with the “laughter plague.” The closure created its own problems: Several of the girls returned to their hometown of Nshamba, promptly causing more than two hundred of the 10,000 residents of the town to descend into uncontrollable giggling. It is not known whether the girls’ teacher had a

k

in his or her name.

21

Their hilarity quickly spread to 95 of the 159 pupils at the school, and by March the school was forced to close. It is reported that the attacks of laughing lasted from minutes to hours, and although debilitating, did not result in any fatalities. The school reopened in May but was again forced to close within weeks when another 60 pupils were struck down with the “laughter plague.” The closure created its own problems: Several of the girls returned to their hometown of Nshamba, promptly causing more than two hundred of the 10,000 residents of the town to descend into uncontrollable giggling. It is not known whether the girls’ teacher had a

k

in his or her name.

After a few months we had received more than 25,000 jokes, about a million ratings, and a large amount of international publicity. It was around this time that I was contacted by John Zaritsky, an Oscar-winning Canadian documentary maker, asking whether I should like to help make a film based on LaughLab that would examine humor around the world. I quickly agreed, and together we traveled the world looking at what makes different parts of the globe guffaw, titter, and groan.

As part of the film, John invited me to Los Angeles to road test some of the material that was obtaining high ratings. I carefully searched through the database and identified two types of jokes—those that the British found especially funny and those that appealed to Americans. In June 2002, I found myself standing in the wings of the Ice House, a comedy club in Pasadena, California. The MC, a sassy young woman named Debi Gutierrez, was standing on the stage explaining what was about to happen. She described the LaughLab project and said that I would deliver some of the jokes that had proved most popular with the British and that she would deliver the gags that had received high ratings from the Americans. A few moments later and I was onstage. It was another of those surreal moments. Debi opened with a classic:

Woman to a male pharmacist: “Do you have that Viagra drug?”Pharmacist “Yes.”Woman: “Can you get it over the counter?”Pharmacist: “Only if I take two of them.”

Debi managed to mess up the punch line, and the joke fell flat. Not even a titter. Then it was my turn. I decided to open with a “Doctor, Doctor” joke that proved very popular with the British people visiting our virtual laboratory:

A guy goes to the doctor and has a checkup. At the end of the examination, he turns to the doctor and asks how long he has to live. The doctor replies, “Ten.” The guy looks confused, and says, “Ten what? Years? Months? Weeks?” The doctor replies, “Nine, eight, seven . . . ”

Again, it was a tumbleweed moment. You could have heard a pin drop. Or a duck drop, if it’s funnier. After a few more jokes obtained exactly the same negative response, Debi finally produced the only laugh of the session with the improvised opening of a nonexistent joke: “Two faggots and a midget walk into a bar . . . ”

According to our data, about a third of the audience should have found the jokes funny. In reality, that figure was embarrassingly close to zero. So what went wrong? It was horses for courses. The people voting in our experiment represented a wide cross section of the public, whereas the people at the comedy club were into a certain type of comedy—bold, brash, offensive, and aggressive. When it comes to comedy, there is no magic bullet, no single joke that everyone will find really funny. It is a question of matching the joke to the person, and we had missed by a mile. It was a point that was to come up repeatedly when we announced our winning joke at the end of the experiment.

Other books

Edith Wharton - Novella 01 by Fast (and) Loose (v2.1)

True Magics by Erik Buchanan

My Several Worlds by Pearl S. Buck

Frank Sinatra in a Blender by Matthew McBride

Captured by Beverly Jenkins

Claw Back (Louis Kincaid) by Parrish, P.J.

Flight of the Jabiru by Elizabeth Haran

The Truth Behind his Touch by Cathy Williams

El águila de plata by Ben Kane

Scraps & Chum by Ryan C. Thomas