Quirkology (29 page)

Authors: Richard Wiseman

Saroglou argues that there is a natural incompatibility between religious fundamentalism and humor.

30

The creation and appreciation of humor requires a sense of playfulness, an enjoyment of incongruity (“Two fish in a tank . . . ”), and a high tolerance for uncertainty. Humor also frequently involves mixing elements that don’t go together, that threaten authority, and that contain sexually explicit material. In addition, the act of laughter involves a loss of self-control and self-discipline. All these elements, argues Saroglou, are the antithesis of religious fundamentalism, and research shows that those who subscribe to it tend to value serious activities over playfulness, certainty over uncertainty, sense over nonsense, self-mastery over impulsiveness, authority over chaos, and mental rigidity over flexibility. Saroglou supports his argument by noting that many scholars have written about the deep mistrust that exists between humor and religion, citing evidence from various religious texts. When discussing examples of biblical humor, Saroglou notes: “One might wonder, for instance, why Christ didn’t simply say ‘blessed are you that weep now, for you shall laugh’ (Lk 6:21), but went on to add ‘woe to you that laugh now, for you shall mourn and weep’ (Lk 6:25).”

30

The creation and appreciation of humor requires a sense of playfulness, an enjoyment of incongruity (“Two fish in a tank . . . ”), and a high tolerance for uncertainty. Humor also frequently involves mixing elements that don’t go together, that threaten authority, and that contain sexually explicit material. In addition, the act of laughter involves a loss of self-control and self-discipline. All these elements, argues Saroglou, are the antithesis of religious fundamentalism, and research shows that those who subscribe to it tend to value serious activities over playfulness, certainty over uncertainty, sense over nonsense, self-mastery over impulsiveness, authority over chaos, and mental rigidity over flexibility. Saroglou supports his argument by noting that many scholars have written about the deep mistrust that exists between humor and religion, citing evidence from various religious texts. When discussing examples of biblical humor, Saroglou notes: “One might wonder, for instance, why Christ didn’t simply say ‘blessed are you that weep now, for you shall laugh’ (Lk 6:21), but went on to add ‘woe to you that laugh now, for you shall mourn and weep’ (Lk 6:25).”

Additional evidence comes from a monastic rule regarding priests playing with children: “If a brother willingly laughs and plays with children . . . he will be warned three times; if he does not stop, he will be corrected with the most severe punishment.”

Eager to test his hypothesis empirically, Saroglou conducted an unusual experiment.

31

In one part of the study, participants completed a questionnaire measuring their level of religious fundamentalism and rated the degree to which they endorsed various ideas, including whether a particular set of teachings contain fundamental truths, that these truths are opposed by evil forces, and that they must be followed via a set of well-defined historical practices. In another part of the experiment, the participants were shown a set of twenty-four pictures depicting a variety of frustrating everyday situations and asked to note down how they would react. After the participants completed the picture task, the researchers rated the degree of humor in their responses. For instance, one of the cards showed someone falling to the ground in front of two friends, with one of the friends asking, “Did you hurt yourself?” A straight-faced response to this card might be something like “No, I am fine,” but “I don’t know, I haven’t reached the ground yet” would constitute a far more humorous approach. In line with his prediction, Saroglou found a strong relationship between religious fundamentalism and humor, the fundamentalists producing far more serious-sounding answers than others.

31

In one part of the study, participants completed a questionnaire measuring their level of religious fundamentalism and rated the degree to which they endorsed various ideas, including whether a particular set of teachings contain fundamental truths, that these truths are opposed by evil forces, and that they must be followed via a set of well-defined historical practices. In another part of the experiment, the participants were shown a set of twenty-four pictures depicting a variety of frustrating everyday situations and asked to note down how they would react. After the participants completed the picture task, the researchers rated the degree of humor in their responses. For instance, one of the cards showed someone falling to the ground in front of two friends, with one of the friends asking, “Did you hurt yourself?” A straight-faced response to this card might be something like “No, I am fine,” but “I don’t know, I haven’t reached the ground yet” would constitute a far more humorous approach. In line with his prediction, Saroglou found a strong relationship between religious fundamentalism and humor, the fundamentalists producing far more serious-sounding answers than others.

As is almost always true with research showing a relationship between two factors, it is difficult to separate cause and effect. Perhaps having a poor sense of humor leads to a fundamentalist religious belief. Or maybe, as Saroglou hypothesized, being a fundamentalist prevents people from seeing the funny side of life. To help disentangle these two possibilities, Saroglou carried out a second study.

32

This time he split participants into three groups. One group saw funny footage from famous French comedy shows. A second group saw religiously oriented footage, including a documentary film about a pilgrimage to Lourdes, scenes from

Jesus of Montreal,

and a discussion between a journalist and a monk about spiritual values. A third group didn’t see any film footage at all, and so acted as a control. Participants were then asked to complete the same humor production task as before. Overall, the people who had seen the humorous footage produced more than twice as many funny responses as the control group, and those who had seen the religious footage trailed in third place. The clever design of the experiment helped Saroglou differentiate correlation from causation, and suggests that exposure to religious material prevents people from using humor to help ease the stressful effects of everyday hassles.

32

This time he split participants into three groups. One group saw funny footage from famous French comedy shows. A second group saw religiously oriented footage, including a documentary film about a pilgrimage to Lourdes, scenes from

Jesus of Montreal,

and a discussion between a journalist and a monk about spiritual values. A third group didn’t see any film footage at all, and so acted as a control. Participants were then asked to complete the same humor production task as before. Overall, the people who had seen the humorous footage produced more than twice as many funny responses as the control group, and those who had seen the religious footage trailed in third place. The clever design of the experiment helped Saroglou differentiate correlation from causation, and suggests that exposure to religious material prevents people from using humor to help ease the stressful effects of everyday hassles.

The relationship between humor production and religious fundamentalism didn’t stop people from submitting jokes about various deities to the LaughLab experiment. Many of them played on the incongruous idea of an omnipotent, caring God behaving out of character:

A shipwreck survivor washes up on the beach of an island and is surrounded by a group of warriors.“I’m done for,” the man cries in despair.“No, you are not,” comes a booming voice from the heavens. “Listen carefully, and do exactly as I say. Grab a spear and push it through the heart of the warrior chief.”The man does what he is told, turns to the heavens, and asks, “Now, what?”The booming voice replies, “

Now

you are done for.”

In a 1939 edition of the

New York Times Magazine,

the Canadian humorist Stephen Leacock remarked, “Let me hear the jokes of a nation and I will tell you what the people are like, how they are getting along, and what is going to happen to them.” Our LaughLab data allowed us to take a scientific look at Leacock’s idea by examining national differences in humor. We were not the first academics to tackle the topic.

New York Times Magazine,

the Canadian humorist Stephen Leacock remarked, “Let me hear the jokes of a nation and I will tell you what the people are like, how they are getting along, and what is going to happen to them.” Our LaughLab data allowed us to take a scientific look at Leacock’s idea by examining national differences in humor. We were not the first academics to tackle the topic.

In chapter 1, I described the groundbreaking research on astrology and personality carried out by the prolific British psychologist Hans Eysenck. During World War II, Eysenck developed an interest in the psychology of humor and did an unusual survey into British, American, and German magazine cartoons.

33

Getting hold of the material proved problematic. Large shipments of American magazines had been lost due to sinkings in the Atlantic, much of the potential British material had been destroyed in the bombings of the British Museum, and the choice of German material was restricted to magazines published before the outbreak of hostilities. Despite the problems, Eysenck soldiered on, and eventually managed to find seventy-five cartoons drawn from various magazines, including

Punch

in Britain, the

New Yorker

in the United States, and

Berliner Illustrierte

in Germany.

33

Getting hold of the material proved problematic. Large shipments of American magazines had been lost due to sinkings in the Atlantic, much of the potential British material had been destroyed in the bombings of the British Museum, and the choice of German material was restricted to magazines published before the outbreak of hostilities. Despite the problems, Eysenck soldiered on, and eventually managed to find seventy-five cartoons drawn from various magazines, including

Punch

in Britain, the

New Yorker

in the United States, and

Berliner Illustrierte

in Germany.

Eysenck then translated the German captions into English and showed all the cartoons to groups of English people. Participants were first asked to rate how funny they found the cartoons. Eysenck discovered that the cartoons from all three countries obtained roughly the same funniness ratings. Next, participants were asked to guess whether each cartoon originated in Britain, the United States, or Germany, allowing the experimenters to analyze the points awarded to the cartoons as a function of where the participants

thought

they were from. The cartoons that people thought were from Germany received much lower ratings than those believed to be from America and Britain. Further analysis revealed additional evidence of national stereotypes. When Eysenck looked closely at the cartoons that people thought were German, he found an overrepresentation of negative elements, including fat women, badly dressed girls, and old-fashioned furniture.

thought

they were from. The cartoons that people thought were from Germany received much lower ratings than those believed to be from America and Britain. Further analysis revealed additional evidence of national stereotypes. When Eysenck looked closely at the cartoons that people thought were German, he found an overrepresentation of negative elements, including fat women, badly dressed girls, and old-fashioned furniture.

In the second part of his study, Eysenck had British, American, and German volunteers (actually refugees who had fled their homeland because of the war) rate the same set of jokes and limericks. His results revealed that, overall, Americans found the material funnier than people from the other two countries, but that there were few differences in the types of jokes that people from different countries found funny.

Our LaughLab data broadly supported Eysenck’s findings. There were large differences in how funny the jokes were to people from different countries. Canadians laughed least at the jokes. This could be seen in one of two ways. Given that the jokes were not very good, it could be argued that Canadians have a discerning sense of humor. Alternatively, they may simply not have much of a sense of humor at all, and so would not find anything funny. Germans found the jokes funnier than people from any other country. The validity of this finding was questioned within the pages of almost every non-German newspaper and magazine reporting our findings. One British newspaper told the top-rated German joke—“Why is a television called a medium? Because it is neither rare nor well done”—to a spokesperson at the German Embassy in London. Apparently, he laughed so much he dropped the telephone and cut off the call. Few other differences emerged. On the whole, people from one country found the same jokes funny and unfunny. The comedian and musician Victor Borge once described humor as the shortest distance between two people. If he is correct, then knowing that diverse groups of people laugh at the same jokes might help bring such groups closer together.

By the end of the project we had received 40,000 jokes, and we had them rated by more than 350,000 people from seventy countries. We were awarded a Guinness World Record for conducting one of the largest experiments in history, and we made the cover story of the

New Yorker.

The top joke, as voted by Americans, was as follows:

New Yorker.

The top joke, as voted by Americans, was as follows:

At the parade, the colonel noticed something unusual going on and asked the major: “Major Barry, what the devil’s wrong with Sergeant Jones’s platoon? They seem to be all twitching and jumping about.”“Well sir,” says Major Barry after a moment of observation. “There seems to be a weasel chomping on his privates.”

Dave Barry had successfully managed to make the top American joke weasel-oriented. He had, thank goodness, less influence over the votes cast by those outside the United States. We carefully went through the huge archive and found our top joke. It had been rated as funny by 55 percent of the people who had taken part in the experiment:

Two hunters are out in the woods when one of them collapses. He doesn’t seem to be breathing and his eyes are glazed. The other guy whips out his phone and calls the emergency services. He gasps, “My friend is dead! What can I do?” The operator says, “Calm down. I can help. First, let’s make sure he’s dead.” There is a silence, then a shot is heard. Back on the phone, the guy says, “OK, now what?”

The joke had just beaten the initial frontrunner, the one about Holmes, Watson, and the strange case of the missing tent, to first place. We contacted Geoff Anandappa, the man who had submitted the Holmes and Watson joke, and broke the bad news. Geoff was gracious in defeat, noting: “I can’t believe I got knocked out in the final round! I could’ve been a contender . . . I want a rematch, and this time I’m going to fight dirty. Did you hear the one about the actress and the bishop?”

The database told us that the winning joke had been submitted by a psychiatrist from Manchester in Britain named Gurpal Gosall. When we contacted Gurpal, he explained how he sometimes told the joke to cheer up his patients; he noted: “It makes people feel better, because it reminds them that there is always someone out there who is doing something more stupid than themselves.”

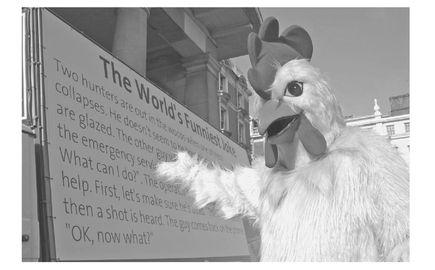

The BAAS and I announced our findings at the third, and final, press conference. For the last time, we hired a chicken suit, and had one of my lucky doctorate students dress up (see

fig. 10

).

fig. 10

).

Fig. 10

Another giant chicken reveals the world’s funniest joke.

Another giant chicken reveals the world’s funniest joke.

Our winning joke was printed on a huge banner and unveiled to the waiting press. Terry Jones, the comedian on the Python team responsible for the sketch involving the world’s funniest joke, was asked by the media for his opinion.

34

He thought the joke was quite funny but perhaps rather obvious. Another journalist interviewed the Hollywood star Robin Williams about our winning entry. Like Jones, Williams thought that is was okay, but went on to explain that the world’s funniest joke is probably absolutely filthy and therefore not the sort of thing you would tell in polite company.

34

He thought the joke was quite funny but perhaps rather obvious. Another journalist interviewed the Hollywood star Robin Williams about our winning entry. Like Jones, Williams thought that is was okay, but went on to explain that the world’s funniest joke is probably absolutely filthy and therefore not the sort of thing you would tell in polite company.

The year-long search for the world’s funniest joke concluded. Did we really manage to find it? In fact, I don’t believe it exists. If our research tells us anything, it is that people find different things funny. Women laugh at jokes in which men look stupid. The elderly laugh at jokes involving memory loss and hearing difficulties. Those who are powerless laugh at those in power. There is no one joke that will make everyone guffaw. Our brains just don’t work like that. In many ways, I believe that we uncovered the world’s blandest joke—the gag that makes everyone smile but very few laugh out loud. But, as with so many quests, the journey was far more important than the destination. Along the way we looked at what makes us laugh, how laughter can make you live longer, how humor should unite different nations, and we also discovered the world’s funniest comedy animal.

Other books

Saved by the Billionbear by Stephani Sykes

Anticipation by Michelle, Patrice

Bloomsbury's Outsider by Sarah Knights

Apocalypsis 1.08 Seth by Giordano, Mario

Underwater by Brooke Moss

The Glass Lady by Douglas Savage

Firefighter Daddy by Lee McKenzie

The Hurlyburly's Husband by Jean Teulé

The Final Shortcut by G. Bernard Ray